G. K. Chesterton (1874-1936) was a truly great Christian author. He was a Christian apologist who wrote with humor, energy, and an infectious joy, as well as startlingly illuminating insights. In a style filled with exuberant paradoxes, Chesterton showed that Christianity is no dull, dreary, life-suppressing institution–as it is often portrayed and as it is often presented even by some of its adherents–but that it is the most stimulating of worldviews, inspiring excitement and wonder at all of life.

Chesterton was also masterful as an intellectual and cultural critic, skewering the “heresies” of his time with a devastating combination of logic and wit. I also appreciate Chesterton for evoking the glorious wonders of ordinary life–the mundane tasks and pleasures that are so common that we take them for granted–and the mystery of simply existing. Reading Chesterton never fails to cheer me up.

Chesterton helped turn lots of folks to Christianity. That includes C. S. Lewis, who learned much about apologetics and effective writing from the master.

So, yes, I am a Chesterton fan. But I’m not sure that I want him to be declared a saint.

There is an effort underway to have Chesterton canonized by the Roman Catholic Church. Chesterton converted to Catholicism in 1922, after most of his apologetic works had been published.

Read this account of the process and where things stand in the National Catholic Register. Right now, the church is trying to decide whether to take the very first steps.

There are reportedly two major obstacles at this point. The first is that Chesterton does not have a “cult”; that is, a group of Catholics who venerate him and who pray to him. Apparently, such grass-roots devotion is the norm–though not strictly required–for those who eventually are elevated to sainthood. I would say that Chesterton certainly has his cult–go to any meeting of the far-flung Chesterton Society, though I don’t believe that meetings begin with a formal invocation of the great man.

More seriously is that Chesterton in his voluminous writings had some negative things to say about Jews. Specifically, he said that Jews could not be fully English. (The same had been said about Catholics.) He was not hateful and did not encourage harming the Jews, unlike many of his contemporaries. Chesterton was known for his robust kindness to everybody. But since the Catholic church today wants to avoid any appearance of anti-semitism, this may be a deal breaker.

A saint is someone who is Heaven. Catholics must go through a rigorous investigation to determine whether a specific Christian has completed his or her term in Purgatory, which may take hundreds or even thousands of years. Evidence that the Christian now inhabits Heaven includes the performing of miracles as a response to prayers, thus proving that the candidate is in a place where he or she can intercede for the living before God.

As a Reformation Christian, I believe that when Christians die, they go directly to Heaven. So I have no problem considering Chesterton to be a saint. Also a sinner, but a sinner who has been cleansed by the blood of Christ.

But I have problems with Chesterton being turned into a saint in the Catholic sense. In his magisterial work of apologetics, Orthodoxy, he says that he is simply defending the points of the Apostle’s Creed. That is to say, Chesterton made the case for what C. S. Lewis called “mere Christianity.”

Chesterton certainly wrote about and defended Catholicism, writing books about St. Francis and Thomas Aquinas and writing some of the basic texts of the economic and social philosophy of “Distributivism,” which would become an important strain of Catholic social teaching.

But making him a Catholic saint would create the impression that he is “just” Catholic.

Chesterton was married with children, and he had robust appetites when it came to food and drink and the pleasures of life. His earthiness would make him quite a different sort of saint from the ethereal ascetics who make up most of the Catholic saints’ calendar. That alone might be a good reason to have a St. Chesterton.

But I think he himself would consider his candidacy for sainthood to be hilarious. That, to me, would demonstrate his sanctity, though in a sense that doesn’t need the inquisitions of Rome.

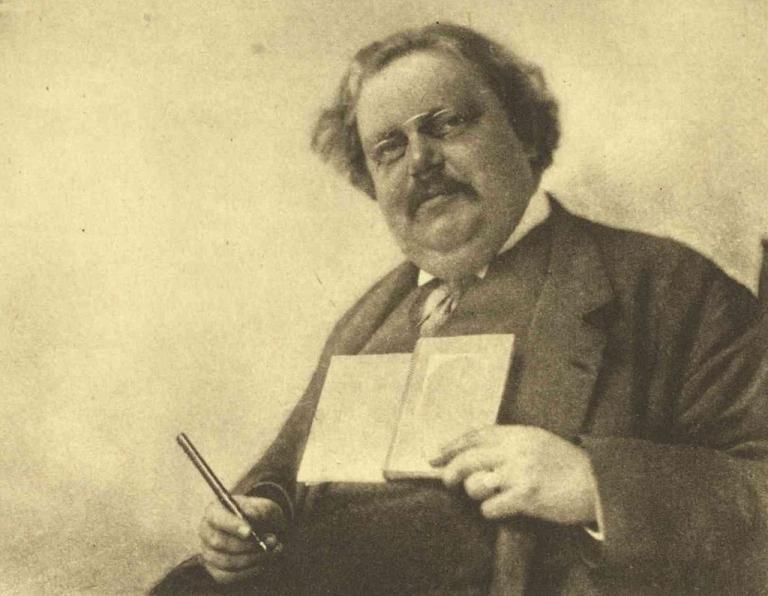

Photo: Chesterton Holding Book and Pen by Hector Murchison [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons