Ancient Rome was the pinnacle of religious toleration, making a point to honor even the gods of their defeated enemies by installing them in the Pantheon. Ancient Rome had an enlightened legal system, protecting individual rights and the principles of justice. And yet, Rome made an exception for Christians, putting aside its toleration and violating its own tenets of justice to outlaw and cruelly punish the followers of Jesus Christ.

Why did Rome do that? And might today’s similarly tolerant and legally enlightened societies do the same?

The Catholic legal expert Carl Herstein has written a fascinating and important article for Public Square entitled Our Return to the Persecution of the Pre-Christian World. He examines just why the Roman persecuted Christianity and sees parallels to the growing legal challenges that Christians are facing today. He is not saying that today’s Christians are in jeopardy of being thrown to the lions or burned as torches to provide light for an emperor’s feast. He is concentrating on the laws and their rationale then and now.

I want to sum up his argument and then draw some lessons from his findings, with reference to options that Christians are currently considering about how to function in an increasingly secularist and culturally hostile climate.

Romans disliked Christians and felt threatened by them because they opposed Roman values and refused to participate fully in Roman public life. Central to the Roman Republic and then the Roman Empire was political participation–running for office, campaigning, voting–but the early Christians cared little for that. Rome was militaristic and glorified war, but the Christians favored peace and often refused to join the army. Rome loved its gladiator fights and related spectacles, but the Christians scorned them. Religion for the Romans was primarily a civic matter, but Christians refused to take part, considering the civil religion in all of its tolerance to be idolatry. Christians were thus a living reproach to what Romans held dear. Of course they were hated.

What Rome wanted from the Christians was submission. Roman law demanded of the Christians, an act of obeisance to Roman values, however small. Just burn some incense to the deified Emperor. That’s all you have to do.

Herstein notes that the Romans violated their own legal principles to extort this concession from the Christians. The legal system was not so enlightened that it rejected torture, but torture was always used to force the accused to confess their crimes. Christians, though, were quite willing to confess the crime of their faith. So with them, the Romans used torture to get them to deny the crime that they were charged with. The goal of the torturers was to force the accused to deny their faith, to apostasize, whereupon they would be released.

Today’s secularist values include non-discrimination, sexual permissiveness, and the right to an abortion. Again, Christians, with their views about gender, sexual morality, and the sanctity of life do not go along with those values. But the secularists insist on submission.

Christians were tortured to cause them to recant and/or to offer the ritual sacrifices that showed their solidarity with the values of the state. So too, is the rapidly developing state of affairs today, although physical torture has been replaced with subtler means, such as economic loss, inability to pursue a trade or profession, loss of a license and even prison. The baker is not punished for having disrupted a gay wedding, but rather for refusing to design and bake a cake for it and thus affirm the values that the state has legitimated. The doctor is not punished for abusing a patient but rather for refusing to perform a procedure that takes a life but which the state decrees ought to be deemed health care.

The unlawful act is thus akin to the Roman Christian’s failure to offer incense as a sacrifice to the emperor; no one cared whether the Christian actually believed that the emperor was a god in any meaningful theological sense (it is highly unlikely that the Roman elite saw the title in much more than honorific terms), but it was seen as of vital importance in affirming the values that the state believed were important—tradition and loyalty. . . .The contemporary notion is that Christians are entitled to believe whatever they wish to believe, as long as that belief is kept private and does not prevent them from making what is, in the eyes of the government, simply a small gesture of respect for the current gods of the state.

Roman persecution of Christians was written into its laws, but it wasn’t always or consistently carried out. Much of the persecution consisted not so much official action on the part of the government but allowing the public to attack Christians with impunity. Similarly, Herstein says that the legal jeopardy religious institutions and individuals often face today is lawsuits from aggrieved parties who allege discrimination or other mistreatment, but the punitive effect of these charges is still considerable.

Read Herstein’s entire article, which includes many more details and examples. Here are some lessons that we might draw from the parallels with ancient Rome:

(1) Cultural withdrawal makes persecution more likely. Some Christians today are saying that we should respond to the hostility of the dominant culture by withdrawing from it. We have lost the culture wars, so we should just form our own separate cultures. I think highly of the Benedict Option, mostly, but we need to realize what to expect.

Cultural withdrawal makes Christians into the “other.” That will increase hostility against us, as happened with the Romans. And it happens whenever individuals and groups of people are mistreated. “They are not like us,” becomes “they are less than human,” which becomes “we can hurt them.”

Do we really think the secularists will allow us to peacefully withdraw into our own schools and homeschools, following our own pro-life practices, upholding our own families, churches, and other institutions? Notice how already homeschooling is being demonized, how even the Vice-President’s wife was smeared for teaching in a Christian school that upholds standards of sexual morality, how being pro-life is being portrayed as an evil, how Christians are being dehumanized. Laws and policies are being proposed that would punish such violations of the society’s values.

Not that Christians should necessarily flee persecution, though the Bible allows for it under some circumstances (Acts 8:1). But we must understand that separating ourselves from the secularist society will not protect us from persecution. Rather, it will probably make it worse.

(2) Our protection from persecution is our rights and liberties. Our society, for all of the secularism of those with cultural power, still has strong cultural and personal ties to Christianity. In America, Christians are not “other” to the extent they were in Rome. We have Constitutional rights to religious freedom. Our legal system offers important protections for Christians that the Roman system, for all of its virtues, did not. The secularists may hate us for our beliefs, but they cannot easily get rid of us. As long as we can, we will have to stand on those rights, litigate them, and not go away.

This is therefore not the time to fantasize about “integralism” or “dominionism” or otherwise taking over the country. There is no way in this secularist culture that Christians can implement Biblical law or set up the Pope as the temporal authority. Such theoretical dreams are not only impossible but theologically wrong, since Christianity has to do mainly with the Gospel, not the Law.

But at the same time, complete separation from politics and from the larger non-Christian society is not right either, given our vocations in the world, including our vocations as citizens.

As a group we may not rule, though individual Christians, by virtue of their vocations, may exercise political offices. But, as long as we are still engaged politically, we can have a say. We can have allies. We can be part of coalitions. Different factions might compete for our support. We would be much harder to persecute.

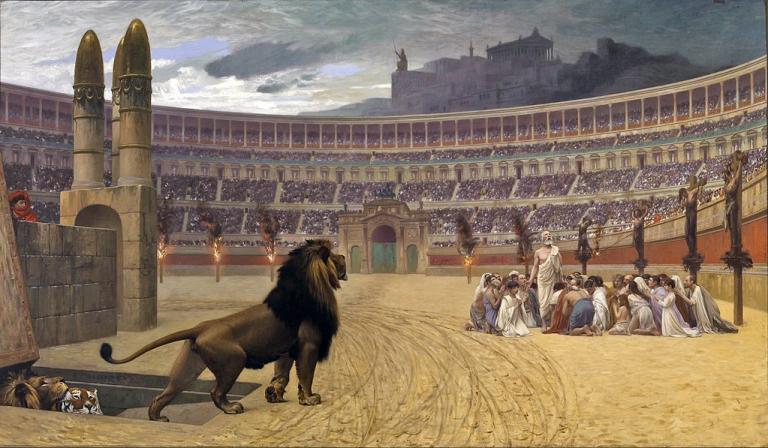

Painting: “The Christian Martyr’s Last Prayer” (1883) by Jean-Léon Gérôme / Public domain via Wikimedia Commons