In my opinion, informed by decades of literary study, one of the greatest stories in literature is Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. It has inspired a contemporary film, The Green Knight, which–though well-done in many respects–completely reverses the medieval tale’s original meaning, perhaps suggesting where our post-Christian mentality is heading.

The anonymous narrative poem of the 14th century, written in an obscure English dialect, is full of twists and surprises, with a brilliant structure, both comedy and thrills, and profound themes of both culture and faith.

I urge you to read it in J. R. R. Tolkien’s translation, collected in his book Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, The Pearl, and Sir Orfeo. This is one of Tolkien’s greatest works, bringing together his vocations as a medieval scholar, a linguist, a literary artist, and a master of imaginative fantasy. Tolkien was, like C. S. Lewis, an academic in his day job; and both Tolkien and Lewis are still highly respected in their fields of literary history to this very day, and by fellow-scholars who would never read The Lord of the Rings or Christian apologetics. Tolkien not only understands this chivalric romance and emulates its power as a fantasy, he also brings into modern English the poem’s rhythm, alliteration, and rhyme scheme–something almost never even attempted, let alone brought off successfully, in translations.

Let me briefly tell you the main elements of the tale. And then I’ll tell you what the movie does with it.

Spoiler alert!

The Original

The story begins on New Year’s Eve in the early days of Camelot. Still celebrating the 12 days of Christmas with a feast, the young, energetic King Arthur, the beautiful Guinevere by his side, proclaims that he will not eat until he has witnessed some adventure.

Whereupon a giant green knight rides into the hall on his green horse, carrying an axe. Despite this breach of etiquette (horses are to be left outside), King Arthur welcomes him. The Green Knight proposes a game of trading blows. A knight may give him his best shot with the axe. And then, in a year and a day, it will be the Green Knight’s turn to strike the knight.

Young King Arthur wants to do it, but his court restrains him, so the young but already accomplished Sir Gawain takes up the challenge. (In the Arthurian tales of Celtic Britain, Sir Gawain becomes the greatest of the knights. Later, in the French versions, bringing in the theme of courtly love, the greatest knight is a Frenchman, Sir Lancelot. In Sir Thomas Malory’s synthesis of the traditions, this will later lead to the civil war that destroys the civilization King Arthur has built.)

Sir Gawain, agreeing with the terms, goes up to the intruder, who bares his neck, and with one blow of the axe cuts off his head. That would seem to be that. But then the decapitated body of the Green Knight stands up and picks up his bloody head, which speaks: I will see you in a year and a day at the Green Chapel.

The Green Knight is a vegetation deity, representing the old nature-based paganism that Christianity was supplanting in Britain. Of course, if you cut off the head of a plant, it just grows back, something we are well aware of every time we mow the lawn. Not so with human beings. The story depicts a test for the new religion and for the new cultural values that Camelot represents: Will this new order of knights, supposedly so superior to the old pagan warriors, keep their promises?

The year passes, with vivid and suspense-building descriptions, as Gawain gets closer and closer to the date of his certain doom. When the time comes, he does as he promises, setting off on a quest to find the Green Knight and this mysterious Green Chapel, not having a clue where they might be. But he sets forth anyway. Unlike conventional quests to find a glorious treasure, this one, as far as Gawain is concerned, is a quest for his death.

After many hard adventures, Gawain, starving and in ice-encased armor, comes to a castle. Here he is warmly received. A friendly, hearty knight named Bertilak is delighted to entertain a knight from Camelot who has come all this way into the hinterlands. And he says that he knows where the Green Chapel is, which is quite nearby. He invites Gawain to rest up and to sleep in, while he himself goes hunting. He proposes a friendly exchange: He will give Gawain whatever he gets on his hunt, and Gawain will give him whatever he receives while back at the castle. (Again: Will a knight keep his promises?)

The next morning, while Gawain is luxuriating in bed, Bertilak’s beautiful wife comes into his bedchamber. Gawain is aghast at this impropriety, but because of his courtesy and his chivalrous concern for women, both hallmarks of Camelot, he does not want to berate her or embarrass her. As she asks about the fashions at court, though, she becomes more and more flirtatious. Gawain pretends not to notice, and at the end of the morning, she leaves, but gives him a chaste kiss on the cheek. When her husband gets back, he gives Gawain the deer he has slain, and Gawain honors their agreement by kissing him on the cheek. (Note the moral test: Will this Christian follow the sexual morality he says he believes in, and resist committing adultery?)

The next day goes much the same, with Bertilak’s hunt being much more difficult, going after a wild bore that attacks him, and his wife’s “hunt” also intensifying, as she becomes more and more aggressive. Again, Sir Gawain fends off her and his own passions, and settles for another chaste kiss, which he returns to her husband.

On the third day, though, the wife just comes out with her desire to have sex with Gawaine, and he forthrightly–but with chivalrous consideration for her–refuses. She says that she understands and, to show that there are no hard feelings, she gives him the gift of a magic green belt. Wear it, she says, and no harm can come to you.

Suddenly, we readers, along with Gawain, are reminded of the main plot: The rendezvous with the Green Knight! This can protect him! Gawain gladly takes the belt. But when Bertilak comes back, giving him the only fruit of a bad hunt, a mangy fox, Gawain gives him a kiss, but keeps the belt for himself, thus violating their agreement.

He goes to the Green Chapel and meets the Green Knight. “Now bare your neck like I did!” Gawain does, but as the axe is raised to strike and starts to come down, he flinches. “I didn’t flinch when you did that to me!” “Well, I won’t be able to pick up my head and ride off like you did!” Again, he prepares himself for the blow, but he flinches again. The third time, the axe misses, merely scratching his neck! Gawain jumps up, draws his sword, says you’ve had your blow, and is ready to fight. Whereupon the Green Knight starts to laugh.

“You have passed the test, or at least done well enough.” The Green Knight turns out to be Bertilak. The real test was not in the Green Chapel but in the bedroom. Chivalry and Christian morality were proven. “You only failed once, in desiring to protect your own life, but that is understandable.”

Gawain is abashed, though, at how he depended on a pagan talisman to protect him, instead of Jesus and His Mother, who were painted on the inside of his shield. He goes back to Camelot, which rejoices to see him, and confesses to all his failure and dishonor. Whereupon the King and the court laugh. They all resolve to wear a green belt in his honor, to remind them all of that crucial chivalrous and Christian virtue of humility.

The Movie

The movie is well-made, with strong acting and gorgeous cinematography. It even picked up on some of the original story’s themes, giving me high hopes. Even material it added seemed to be in line with the original (such as the bit it added with Gawain’s mother Morgause, the sister of both Arthur and Morgan le Fay, whom the book credits for orchestrating the test.) But then the movie switched the themes around.

Whereas the original tale was set at the beginning of King Arthur’s reign, the movie presents it at the end. Arthur is old, weak, and decrepit, still noble, but approaching his end. The book, as it were, dramatized the beginning of Christendom to a recently and probably not completely converted Celtic audience. The movie depicts Christianity and the Western Civilization it created as being essentially over.

Instead of the way the book shows paganism giving way to Christianity, the movie shows Christianity giving way to paganism. For example, Bertilak’s castle is full of books, which Gawain marvels at to the wife, who says she has read or written them all. Christianity is presented as backwards, while paganism is presented as a well-spring of learning and education. Which violates history completely! In reality, Christianity in the middle and the previous dark ages was responsible for books and learning, while paganism, as depicted in the book, is about instincts, passion, and irrationalism.

The movie includes the original’s riff on the number 5 as symbolizing the five fingers, the five senses, the five knightly virtues, the five wounds of Christ, the five joys of Mary, etc., but presents it as a magical incantation rather than a confession of how his faith must impact his life. It shows the inside of Gawain’s shield, with its icon of Mary and Jesus, only to have robbers throw it on the ground and cut it in two.

In the movie, Gawain is not even a knight, even though the title of the source book specifies “Sir Gawain. . . ” Rather, he is presented as a clueless youth–though portrayed by a mature man–who wants to be a knight, something he associates with “honor,” with little reference to what that entailed back then.

And the movie doesn’t even consider the virtue of chastity. Gawain is shown at the beginning frequenting brothels. He has a sexual relationship with a lower-class Essel, but he is oblivious to her love for him and treats her despicably, unlike the way actual chivalry would demand.

And Gawain immediately gives in sexually to Bertilak’s wife so that she will give him the magic belt. Here the movie comes off the tracks completely, in leaving out the best and most important part of the original story. The three days of temptation and resistance, paralleling Bertilak’s three hunts, is eliminated completely, crunched into one day with a sex scene, ending with a shot of semen on the green belt.

The old paganism was at least a fertility religion. This newly emergent paganism wants sex, but not fertility, which entails having children and generating new life. Reflecting our new pornographic view of sex, this one is more of a masturbatory religion.

As for the ending, Gawain does flinch from the Green Knight blow and seems to run away, whereas, in a long and confusing sequence, we see his unhappy life unfold. But that turns out be only a vision, from which he wakes up and says he is ready for the blow. The Green Knight speaks kindly to him, but then says, “Now, off with your head!” Fade to credits.

That abrupt, non-conclusive ending prevents any kind of happy ending, which is a necessity in every fairy tale. Nature brings death, the film seems to say, but that is better than the pointless life you would have lived.

The problems of the film are not just the thematic inversions from the original. They are also artistic, as elements are thrown in without being accounted for (such as the naked female giants that parade through) and loose ends are never tied together (such as Bertilak not being revealed as the Green Knight).

There was another more subtle problem that grated on me. The movie is full of “thee’s” and “thou’s,” which I appreciate as being an attempt to evoke medieval language (though it is actually Early Modern). But if you are going to use those pronouns, use them correctly! In the movie, King Arthur gives a wimpy speech to his knights, in which he gives credit for all of his accomplishments “to thee.”

“Thee” is a singular! “Thou” is the subject form, “thee” is the object form, and “thy/thine” are the possessives. “Ye” is the plural subject form (as in “go ye into all the world and preach the gospel), and “you” is the plural object form, with “your/yours” being the possessive.

These distinctions acquired a social distinction, with the singular forms (“thou, thee, thy”) becoming an intimate address reserved for family and close friends. (It was also used to address God, our most intimate friend of all.) The plural forms (ye, you, your) were used to address social superiors. But it was also still used as a plural, when addressing more than one person.

Eventually, we lost all distinctions and use “you” for everyone. But no one in the Middle Ages or the early modern period would address a group as “thee”!

Read this for the grammar and this for the difference it makes in reading Shakespeare.

What this tells me is that the filmmakers of The Green Knight do not understand medieval history, language, or religion. Unlike J. R. R. Tolkien.

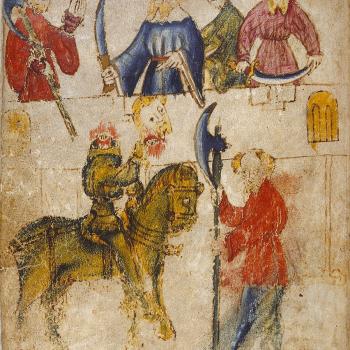

Illustration: From the original manuscript of “Sir Gawain and the Green Knight” (14th century) by Unknown author – http://gawain.ucalgary.ca, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=621711