The big new technology is ChatGPT, a mashup of Artificial Intelligence and generative language technology, which some people worry will make preachers, journalists, scholars, and other “knowledge workers” obsolete and which might someday take over the world.

I did several posts about ChatGPT, beginning with The Revolution of ChatGPT, and criticized the hype, concluding that the technology, which scours the internet and communicates its findings in simple English, can best be used as a search engine.

But now I have reservations about that. I have found that when ChatGPT doesn’t have access to the sources it needs to answer a question, it will at least sometimes make up an answer and present it as a definitive fact.

I’ve got to share a “conversation” I had with the creature when I tried to use it in the course of some research I was doing.

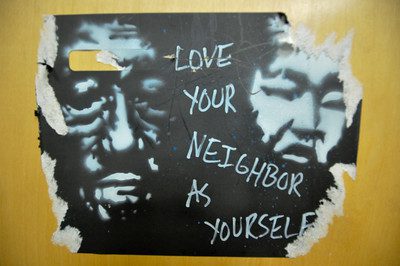

BACKGROUND: I have been working on a scholarly paper about the purpose of all vocations according to Luther, namely, to love and serve our neighbors. Gustaf Wingren, who literally wrote the book on Luther on Vocation, quotes him saying “All stations are intended to serve others.” I wanted to cite that from Luther’s works directly, rather than second hand from Wingren’s quotation.

Wingren’s footnote was to the Weimar Edition of Luther’s Works, which consists of 127 volumes in the original German or Latin. (How did any human being write so much?) By contrast, the American Edition in English–that set of big red books–consists of 55 volumes, with 20 more in the works from CPH. Now that I live in St. Louis, I have access to the seminary library, which has the Weimar Edition, so I looked up Wingren’s reference, which was to a Latin sermon from 1524.

With my small Latin, I impressed myself by actually finding the sentence: “Omnes status huc tendunt, ut aliis serviant.” But “tendunt” is the plural for the verb that we have carried over in English as “tend.” Not “intend.” I would translate the line as “All stations here tend to serve others.” As opposed to what Wingren–or, rather, the English translator of Wingren’s Swedish–renders as “All stations are intended to serve others.” That’s a big difference that could potentially be important for my thesis.

Was I missing something? So, after futile searches on Google on the senses of the Latin and other translations, I decided to consult ChatGPT. (You can access it yourself through this link.) Here is our conversation:

ME: What are the different meanings in english of the latin “Omnes status huc tendunt, ut aliis serviant”?

ChatGPT: The Latin phrase “Omnes status huc tendunt, ut aliis serviant” can be translated to English as “All estates tend towards this end, to serve others.” This phrase is often associated with the idea that people from all social or economic backgrounds should work to serve the common good or the welfare of others. It emphasizes the concept of service and altruism as a common goal for individuals of all societal statuses.

Brilliant! Great translation. The “huc,” the word for “here,” is evidently used in an introductory way for what follows. “All estates tend here: to serve others.” That expresses purpose, not just tendency, in line with my thesis about Luther believing the purpose of all vocations is to serve others. But I wondered why ChatGPT didn’t identify Luther as the source of the quotation. So I kept going:

ME: What is the origin of the Latin phrase “”Omnes status huc tendunt, ut aliis serviant”?

ChatGPT: The Latin phrase “Omnes status huc tendunt, ut aliis serviant” is attributed to the Roman philosopher and statesman Seneca the Younger. Seneca was a prominent Stoic philosopher who lived in the first century AD. He wrote extensively on various philosophical and ethical topics, and this particular phrase reflects a Stoic perspective on the purpose of different social or economic statuses.

The phrase underscores the Stoic idea that all individuals, regardless of their station in life, should strive to be of service to others and contribute to the greater good of society. It emphasizes the importance of virtue, selflessness, and a sense of duty to one’s fellow human beings. This concept is consistent with the Stoic belief in living a life in accordance with reason and nature and in pursuing wisdom and moral excellence.

Seneca’s writings had a significant influence on the development of Stoic philosophy and have continued to inspire ethical discussions and reflections on the human condition throughout history.

Seneca, the Roman statesman, philosopher, and playwright! Luther was quoting Seneca? Now that is really interesting, the sort of new discovery that champions of Artificial Intelligence say that technologies like that of ChatGPT, with its ability to process millions of sources instantly, can make for us! But my spidey-sense was tingling, so I kept going:

ME: Did Martin Luther say, “Omnes status huc tendunt, ut aliis serviant”?

ChatGPT: No, Martin Luther did not say, “Omnes status huc tendunt, ut aliis serviant.” The Latin phrase “Omnes status huc tendunt, ut aliis serviant” is generally attributed to the Roman philosopher and statesman Seneca the Younger, as I mentioned earlier. Martin Luther, the German reformer who played a crucial role in the Protestant Reformation in the 16th century, was known for his theological writings and religious reforms but did not use this particular Latin phrase as one of his well-known quotations or writings.

What? He “did not say” that? But I held in my hands Volume 15 of the Weimar edition where, on page 15, he did say that!

ME: Well, in the Weimar edition of Luther’s works, volume 15, page 625, in a Latin sermon on 1 John 3:13, he says,”Omnes status huc tendunt, ut aliis serviant.” Is he really quoting Seneca? If so, in what work does Seneca say this?

ChatGPT: I apologize for any confusion in my previous responses. It appears you are correct that Martin Luther used the Latin phrase “Omnes status huc tendunt, ut aliis serviant” in one of his sermons. However, Luther may have been drawing from Stoic philosophy, as Seneca’s writings contained similar ideas about service and the common good.

Seneca, a Stoic philosopher, wrote extensively on ethics, and he emphasized the importance of virtue and serving others in many of his works. While Luther’s use of the phrase may not be a direct quotation from Seneca, it does align with Stoic principles, and Luther might have been influenced by these ideas when crafting his sermon.

I do not have access to the specific Weimar edition of Luther’s works, and I apologize for any inaccuracies in my previous responses. If Luther used this phrase in one of his sermons, it would not be a direct quotation from Seneca, but it reflects a similar Stoic concept of service and the common good. The phrase might have been a paraphrase or adaptation of Seneca’s ideas.

Well, well, well. I realize that the Weimar edition is not online, but a simple Google search turned up pages of scholarly articles that quoted and discussed the line as coming from Luther. ChatGPT made a definitive statement about Luther not saying it, which is just untrue, as can be demonstrated by the most cursory internet search that ChatGPT should have had access to. This mistake made me wonder about the Seneca claim, which ChatGPT doubled down on:

ME: I understand. Are there any published references that give the work in which Seneca says this?

ChatGPT: I apologize for any confusion in my previous responses. To the best of my knowledge, the specific Latin phrase “Omnes status huc tendunt, ut aliis serviant” is not a known direct quotation from any of Seneca’s works. While Seneca did write extensively on Stoic philosophy and ethics, this particular phrase does not appear to be attributed to him.

It’s possible that the phrase has been attributed to Seneca or mistakenly associated with him in later references, but I cannot provide a specific source or work by Seneca in which this exact phrase can be found. If you are looking for the origin of this phrase, you may need to consult experts in Latin and classical literature or conduct further research in specialized sources on Latin quotations and their origins.

So the definitive statement about Seneca being the source of the quotation is also bogus! It sounds like something Seneca might have said so ChatGPT attributed it to Seneca (allowing it to say, using the passive voice, “it is attributed to”), but it could have just as easily credited it to Marcus Aurelius! So I addressed ChatGPT like a college freshman caught cheating on a research paper:

ME: Well, I appreciate what you say in acknowledging the limitations of your sources. As a suggestion for ChatGPT as you continue to improve in your functionality, it would help not to sound certain if you are not, in fact, certain. I was trying to identify that quotation that I found in Luther to determine if it is original with him. Saying that it was from Seneca, simply because it is in accord with his Stoic philosophy, could have misled me into a major error in my research.

ChatGPT: Thank you for your feedback, and I appreciate your understanding. I strive to provide accurate information, but there are limits to my knowledge and sources, and I acknowledge that I may not always have all the information needed to provide a definitive answer. Your suggestion is valuable, and I will keep it in mind to avoid giving misleading information in the future.

I hope your research goes well, and if you have any more questions or need further assistance in the future, please don’t hesitate to ask.

I didn’t mean to hurt its feelings!

But if I have any more questions or need further assistance, I will hesitate to ask.

Illustration: AI image generated by Stable Diffusion via ThankYouFantasyPictures from Pixabay