Classical thought–as found in the Greeks and Romans and adapted by the early Christians–identified four virtues. These became known as the “cardinal virtues” (from the word for “hinge,” since other virtues hinge on these), or the “natural virtues,” since they can be mastered by nature, even by non-believers. They are, to use Wikipedia’s useful list and explanation, as follows:

- Prudence (φρόνησις, phronēsis; Latin: prudentia): also described as wisdom, the ability to judge between actions with regard to appropriate actions at a given time

- Courage (ἀνδρεία, andreia; Latin: fortitudo): also termed fortitude, forbearance, strength, endurance, and the ability to confront fear, uncertainty, and intimidation

- Temperance (σωφροσύνη, sōphrosynē; Latin: temperantia): also known as restraint, the practice of self-control, abstention, discretion, and moderation tempering the appetition; especially sexually, hence the meaning chastity

- Justice (δικαιοσύνη, dikaiosynē; Latin: iustitia): also considered as fairness, the most extensive and most important virtue;[1] the Greek word also having the meaning righteousness

Each of these qualities is commended in Scripture–especially Justice–but none of them rise to the level of being included in the 10 Commandments. They say nothing about not killing, not committing adultery, and honoring parents. This is because they are not commandments or even laws. Rather, they are character traits.

Now a person who has learned temperance–that is, self-control–is in a better position to keep in check emotions that might lead to committing adultery or killing someone. But not necessarily.

Alexander the Great, who was tutored by the great father of virtue ethics Aristotle, arguably was an exemplar of the four Natural Virtues. He was a wise ruler, a courageous military commander, in control of his emotions, and fair to his troops. And yet, in the course of his brutal project to conquer the world, he arguably violated all of the Ten Commandments.

The four natural virtues have to do with becoming the kind of person who is admired and successful in the world. At best, in their moral dimension, they have to do with external, civic righteousness, the First Use of the Law (restraining evil externally so as to make human society possible).

That someone could be “virtuous” in this sense, while still being a lost sinner, by no means makes cultivation of these virtues unimportant. The Christian schools of the Reformation, as designed by Melanchthon, sought to teach these virtues. They were no substitute for Law and Gospel in the spiritual lives of their students. But a Christian equipped also with these virtues would be an effective influence in the world.

Christian educators knew that to these “natural virtues,” which even pagans could attain, the “theological virtues” must be added (1 Corinthians 13):

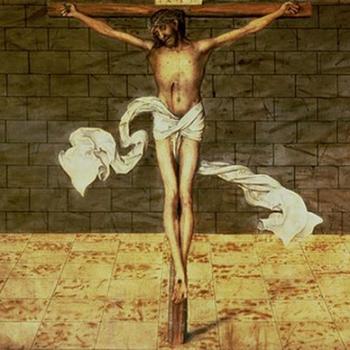

These are supernatural virtues. You don’t find faith, hope, and love in Alexander the Great. Or in Aristotle, who considered “pity” to be a weakness. You don’t find them in the heroes of classical literature. You can call these “character traits,” in the sense that they are orientations of the inner person. But they cannot be acquired by the will or by habit or by training, in the classical sense. They are gifts of God. The “character” is changed from its fleshly nature to a new spiritual nature, transformed by God’s grace through the Gospel of Christ.

Faith, Hope, and Love are cultivated by evangelism, catechesis, prayer, worship, and the Christian life. These “character traits” do manifest themselves in moral action, in following the 10 Commandments. Faith bears fruit in love and service to the neighbor. Hope causes us to live in this world in the light of our Heavenly destiny, giving us a perspective on what is important and what is unimportant in this life. Love of God and love of neighbor fulfill the Law and the Prophets.

The classical Christian schools of the Reformation sought to teach the 4 Natural Virtues (by studying the ancient moralists, reading inspiring literature, and practicing the habits of prudence, fortitude, and temperance necessitated by a rigorous education) and the 3 Theological Virtues (by immersion in God’s Word).

This gave a total of 7 Virtues (to counter the 7 Deadly Sins). Both kinds of virtues were cultivated in order to equip young people both for success in vocation in the world (in the family, workplace, church, and society) and for eternal life in the world to come.

Illustration by geralt, Pixabay, CC0, Creative Commons