It’s an interesting poem for lots of reasons. Two lines in it, though, almost kept his whole book from getting published:

Religion stands on tip-toe in our land,

Readie to passe to the American strand. (lines 259-260)

Herbert felt that Christianity was dying in England. Sin will grow to the point that it corrupts the church.

Then shall Religion to America flee:

They have their times of Gospel, ev’n as we. . . .

Yet as the Church shall thither westward flie,

So Sinne shall trace and dog her instantly:

They have their period also and set times

Both for their vertuous actions and their crimes. (lines 272-273, 290-293)

The king’s censors in 1633 did not approve of Herbert’s criticism of the Church of England, particularly his insinuation that those who were fleeing religious persecution by emigrating to the American colonies, such as the one at Plymouth, were saving Christianity. Fortunately, Herbert’s editor, the devout Anglican Nicholas Ferrar had clout at court and got the censorship overruled. (See Philip Jenkin’s discussion of this poem and its historical context.)

But Herbert’s words here and in the whole poem feel eerily prophetic, being much more true in 2024 than they were in 1633.

Luther says something similar (which may have given Herbert his idea) in To the Councilmen of All Cities in Germany That They Establish and Maintain Christian Schools (my bolds):

Germany, I trow, has never heard so much of God’s Word as now; at least we find nothing like it in history. If we permit it to go by without thanks and honor, it is to be feared we shall suffer a still more dreadful darkness and plague. Buy, dear Germans, while the fair is at your doors; gather in the harvest while there is sunshine and fair weather; use the grace and Word of God while they are here. For, know this, God’s Word and grace is a passing rainstorm, which does not return where it has once been. It came to the Jews, but it passed over; now they have nothing. Paul brought it to the Greeks, but it passed over; now they have the Turk. Rome and the Latins had it, too; but it passed over; now they have the pope. And you Germans must not think you will have it forever; for ingratitude and contempt will not suffer it to remain. Take and hold fast, then, whoever can; idle hands cannot but have a lean year.

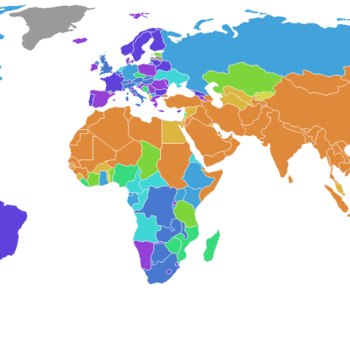

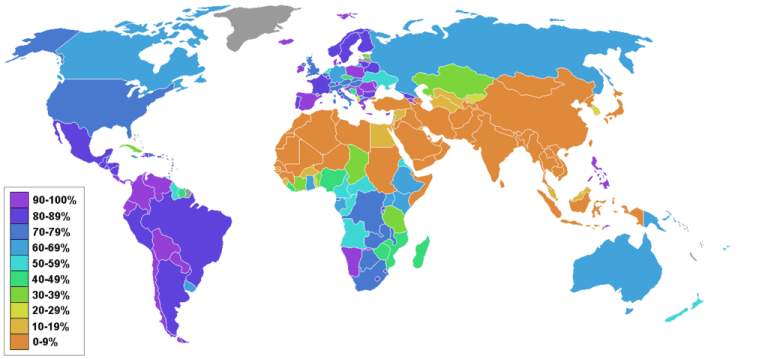

As secularism takes over Western Europe and as the “American strand” is rapidly heading that way, some are saying that the major center of Christianity in the world is shifting to Africa.

According to these 2020 numbers from Gina A. Zurlo, Co-Director, Center for the Study of Global Christianity, in the post Who Owns Global Christianity?, Africa has more Christians than any other continent, with 667 million. Then comes South America, with 612 million. Then Europe with 565 million. Then Asia with 379 million. Then North America with 268 million. And, finally, Oceania with 28 million.

According to Dr. Zurlo’s graphs, Africa currently is home to about a third of the world’s Christians. But the population trend lines project that this number will shoot up to 50% by the year 250.

Not only is Christianity growing dramatically in Africa, African churches tend to be more orthodox than many of their counterparts in the rest of the world. When the pope permitted blessings for same-sex couples, African bishops refused to comply. African Anglicans, who far outnumber English Anglicans, are fighting the liberal theology of the Church of England and the U.S. Episcopal Church. African Methodists oppose the leftward bent of the United Methodists in the U.S., which is why the conservative breakaway congregations are forming a distinctly international denomination of “Global Methodists.”

There are 24,135,469 Lutherans in Africa, as compared to 3,672,858 in North America. The largest Lutheran church in the world is the Mekane Yesus (Place of Jesus) church of Ethiopia with some 10.7 million members. The second largest is the Lutheran church of Tanzania, with 7.9 million.

The bishop of the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Kenya, with which the LCMS is in fellowship, has been ordaining bishops and pastors in Scandinavia to bring back confessional Lutheranism to the Nordic lands.

It wouldn’t be unusual for Africa to become the center of global Christianity. The city of Alexandria in Egypt provided much of the intellectual leadership of the early church. St. Augustine, bishop of Hippo in present-day Algeria, was and remains one of the most important theologians of the church, both to Catholics and Protestants.

To be sure, the churches of Africa have their problems–poverty, bad government, lack of education, the Prosperity Gospel, Islamic persecution–but development is starting to take hold. The West, where Christianity is declining, at least has money and expertise and can help with that development.

If the leadership and the dynamic core of Christianity does pass over to the African strand, that doesn’t mean that the faith will disappear in the hinterlands of America and Europe, with their depleted population and their spiritual emptiness. There will be churches, however small, and Christians, however beleaguered. Besides, the Africans will doubtless be sending us missionaries.

Photo: Confirmation of new members, Hola, Tana River County, Evangelical Lutheran Church of Kenya via Facebook