I posted recently about using quotes as springboards for discussions of particular historical eras, and their religious concerns. Sometimes, when you look at that quote in context, it becomes a little more complex, and more interesting. In this case, it leads to an unsuspected political and literary world.

In this post and the next I will be looking at a major poem from George Herbert (1593-1633), who is acknowledged as one of the greatest Christian poets in English, and was one of the greatest poets of seventeenth century Britain. I emphasize Britain rather than England, because by any definition, his family and background were thoroughly Welsh. Herbert’s Five Mystical Songs were set to music by Ralph Vaughan Williams, and he was a huge inspiration for many later writers, especially T. S. Eliot.

But even Herbert’s admirers have found one particular poem of his puzzling or even off-putting, namely “The Church Militant,” which was published posthumously in 1633. One passage of that poem has been very widely quoted, for obvious reasons.

Religion stands on tip-toe in our land,

Readie to passe to the American strand.

A few lines later, he continues,

Then shall Religion to America flee:

They have their times of Gospel, ev’n as we.

I should also note that the “times of Gospel” line is a natural epigraph for any book on Global/World Christianity.

So, “Then shall Religion to America flee?” The context for the American hopes seems obvious enough. This was the time of the English settlement in New England, with the Mayflower in 1620, and in 1630, John Winthrop delivered the sermon with the famous hope that the new Massachusetts Bay colony would stand “as a city upon a hill.” Opinions vary as to when Herbert composed his poem, which might have been any time from the late 1610s onward, but the setting fits perfectly into the general era of the Pilgrims and the Plymouth Colony.

Whether it actually refers to those endeavors in any sense is open to discussion: I will argue that he is tangentially making such a reference, but as part of a larger argument not relevant to the Puritans. I will suggest that “The Church Militant” can be dated with fair accuracy, and to a later point than is commonly accepted. Instead of the mid-1620s, I will date it more precisely to 1629-30. That may sound like a chronological quibble, but it actually helps greatly to understand the context of the work, and its intent. In particular, it muddies the simple Puritan narrative.

I just add that the landing of the Mayflower occurred almost exactly four centuries ago, with November 21 marking the actual landfall. What could be more seasonally appropriate a reading?

Robert Walter Weir, “Embarkation Of The Pilgrims” (1857). Image is in public domain

George Herbert and the Temple

The “Church Militant” has some curious features. Assume for the sake of argument that the poem is referring to the Puritan ventures in New England. But much of Herbert’s appeal for later readers is that he was very “high” church in tone, with an overwhelming sense of the sacramental and clerical. In theory, that should have put him on a very different part of the spectrum to John Winthrop and the New England Puritans. In his Latin poetry, Herbert engaged in a literary duel with the Presbyterian Andrew Melville, who had attacked the Church of England for preserving so many alleged vestiges of the medieval and Catholic. In response, Herbert defended foundational Anglican practices, including vestments, church music, and of course bishops. He sounds like a classic exponent of the Anglican middle way.

Herbert’s emphasis on priesthood was notable in this context. The collection of poems for which he is best known is simply called The Temple, and priestly ideas and images run throughout. In Aaron, he contrasts the Biblical priest of that name with his own poor efforts as an Anglican cleric: but nevertheless, he too really is a priest. His famous and much-reprinted prose work about living as a country pastor was called A Priest to the Temple.

It is important not to apply the whole idea of “high” church as a uniform or unchanging concept, and it meant something very different indeed in the 1630s than the 1850s, say. Seventeenth century debates over “ceremony” in religion did not necessarily have the connotations that they might have done in later years. But Herbert’s priestly images were sensitive to the point of explosive. In 1646, the worst thing John Milton could find to say about proposed religious reforms was that “New Presbyter is but old Priest writ large.” For many Puritans, the whole idea of priesthood was close to fighting words, and certainly in the sense of an ordained clergy, as opposed to the priesthood of believers. So why was Herbert speaking with such apparent optimism about the creation of these Puritan colonies?

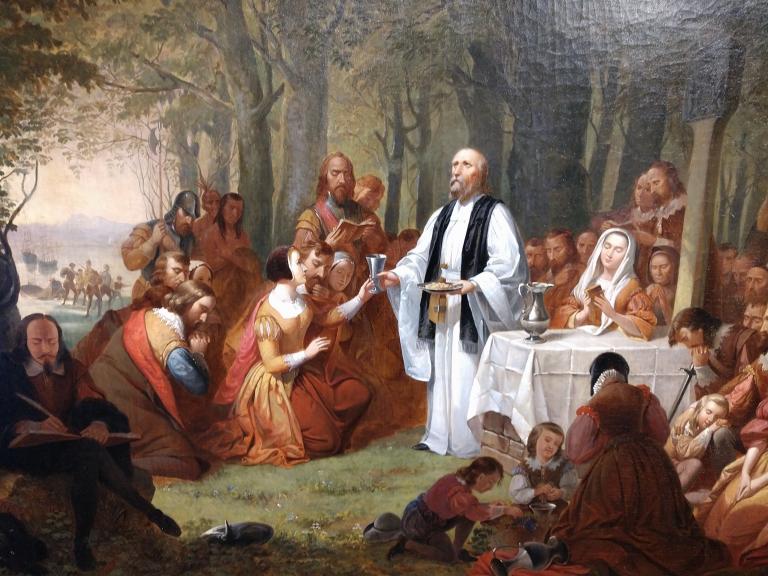

Tompkins Harrison Matteson, “First Communion in the New World” (1858). Photograph is my own work.

Like a Pilgrim, Westward Bent

With that in mind, we can look at the larger “Church Militant,” which has always occupied an odd position in Herbert’s work. Although printed in The Temple, many feel that it scarcely belongs there. Most of the other items are short lyrics, while this approaches 300 lines. For what it is worth, the final structure of the volume was not the work of Herbert, who on his deathbed sent his manuscripts to Nicholas Ferrar, founder of the Anglican community at Little Gidding, immortalized by T. S. Eliot. I will often be returning to Ferrar, and Little Gidding, in this argument. Ferrar was to decide whether to publish the poems or to burn them, and fortunately he chose the former. Herbert – or Ferrar – clearly thought the long poem mattered enormously, as it is the closing piece to the whole volume, barring a short envoi. It represents the ideas that the reader was meant to take away.

What is the poem, and how do the American comments fit? Most strikingly, it is on a dramatic scale in terms of its historical and religious vision. It describes the Church, God’s chosen spouse, who makes her voyage from her birthplace in the east, just as Abraham had traveled west from his country.

Religion, like a pilgrime, westward bent,

Knocking at all doores, ever as she went.

Yet as the sunne, though forward be his flight,

Listens behinde him, and allows some light,

Till all depart: so went the Church her way,

Letting, while one foot stept, the other stay

Among the eastern nations for a time,

Till both removed to the western clime.

This suggests something like a historical law, namely that the Church expands to all nations, but it expires and all but vanishes in its earliest conquests. Herbert’s theme is that Christianity grows strongly in particular nations and societies, but it is very vulnerable to the machinations of Sin, and in his contemporary world, that meant above all the Roman Catholic church, which had been distorted into a very powerful anti-Christian force. This is above all an anti-Papal and anti-Catholic tract.

In each historical case, Herbert lists the mighty achievements of faith in that land – first Egypt, then Greece, Rome, and on to Germany (the Holy Roman Empire) – and shows how Christianity defeated, absorbed, and supplanted older paganisms. But in each instance, he suggests that after faith burned bright in that lands, so it died, before leaping further westward still.

He shows no sense of the continued Christian traditions in his day in Egypt, say, or Greece, which as a well-informed member of the country’s intellectual elite, he should have known very well indeed. The Coptic and Orthodox churches were reasonably well known in the Western Europe of his time, and in his closing years, the Orthodox Patriarch Cyril Lucaris would detonate a furious controversy by attempting to move his church to Calvinist and Western models. But Herbert ignores those inconvenient truths for rhetorical reasons, because they do not fit into his overarching argument, and its central anti-Catholicism. For his purposes, history must show that religion – true religion, that is authentic Christianity – is always heading west, while abandoning the east. To adapt the title of the nineteenth century painting, Westward the Course of Faith Takes Its Way.

Christianity then eventually came to Britain:

Thus both the Church and Sunne together ran

Unto the farthest old meridian.

Sin and Its Plots

But just as the church came out of the east, ultimately from Babylonia, so Sin followed, and spread error, in each individual land:

journeying on

He chid the Church away, where e’re he came,

Breaking her peace, and tainting her good name.

So weakened and compromised were Egypt and Greece that they were given over

To such Mahometan stupidities,

As the old heathen would deem prodigies.

Rome still withstood, but Sin responded deviously, not by overthrowing the church but by subverting it from within. While pretending to be authentically Christian, the Roman Church became a vessel of Sin. Herbert offers a roster of classic anti-Papal and anti-Catholic canards and stereotypes:

From Egypt he took pettie deities,

From Greece oracular infallibities,

And from old Rome the libertie of pleasure,

By free dispensings of the Churches treasure.

Then in memoriall of his ancient throne

He did surname his palace, Babylon. …

Thus Sinne triumphs in Western Babylon;

Yet not as Sinne, but as Religion.

Old and New Babylon (Papal Rome) “are Hell’s land-marks, Satan’s double crest: They are Sinne’s nipples, feeding th’ east and west.” So great is the strength of that New Babylon that a terrible darkness will cover the world at “Christ’s last coming,” which cannot be far removed. So shriveled is true (Christian) religion that at that End Time, it will be as shrunken a remnant of its former self as modern “Jewry” is of the historical Israel. (This is a difficult portion of the poem, but that is my best interpretation).

If you want to understand anti-Catholicism as an ideology in Early Modern England – or Germany, or France – you could do much worse than to turn to the “Church Militant,” and quote it at much greater length than I have done here. Has anyone ever used “Sinne’s Nipples” as a title for a book on the topic?

On to America

If Herbert is right about these inexorable laws of Christian history, then Sin’s next target must be Britain, where the Christian church survives. But it is deeply imperiled by influence from France and Italy – the Seine and Tiber – and it is at this point that we find the celebrated American “prophecy.”

Religion stands on tip-toe in our land,

Readie to passe to the American strand.

When height of malice, and prodigious lusts,

Impudent sinning, witchcrafts, and distrusts

(The marks of future bane) shall fill our cup

Unto the brimme, and make our measure up;

When Sein shall swallow Tiber, and the Thames

By letting in them both, pollutes her streams:

When Italie of us shall have her will,

And all her calender of sinnes fulfill;

Whereby one may fortell, what sinnes next yeare

Shall both in France and England domineer:

Then shall Religion to America flee:

They have their times of Gospel, ev’n as we.

But going ever to the west also involves going full circle, and when the two voyages meet – of Sin and the Church – that is the time of Doomsday and the Judgment.

My reading of the poem is that Herbert is so deeply alarmed by the Catholic threat in the England of his own day that he will contemplate a flight to America.

Carrying First Their Gold From Them Away

At that point, we run into a problem of interpretation, as the very next passage seems to declare a surprising solidarity with the Puritans. even the most radical. He declares,

My God, thou dost prepare for them a way

By carrying first their gold from them away:

For gold and grace did never yet agree:

Religion alwaies sides with povertie.

We think we rob them, but we think amisse:

We are more poore, and they more rich by this.

Thou wilt revenge their quarrell, making grace

To pay our debts, and leave our ancient place

To go to them, while that which now their nation

But lends to us, shall be our desolation.

Who is he talking about? If he is really writing about the Puritans, it is an odd description of the migrants as so crushed and persecuted, which most really had not been. Particularly the migrants of the late 1620s were anything but huddled masses, but were rather solid investors with plenty of available gold. This comes across as a remarkably radical portrait of the Puritan exiles, if indeed it is such.

There is an alternative interpretation, namely that the passage refers instead to a financial meltdown of the mid-1620s, namely the royal termination of the Virginia Company in 1624. Several of Herbert’s key friends, relatives, and associates were deeply involved in this affair, including the Ferrar family, as I will discuss later. This does not mean necessarily that the poem dates from the mid-decade, and as I will show, datable elements point to a date of writing about 1629-30, but that Virginia Company debacle might be in the author’s mind. Some people very close to Herbert did indeed have all their gold carried away in that affair.

Having said that, some people in authority at the time apparently did read it as a pro-Mayflower or pro-Massachusetts Bay poem. In an admittedly later tradition, Izaak Walton records a story about the 1633 publication of The Temple:

When Mr. Farrer [sic] sent this book to Cambridge to be licensed for the press, the Vice-Chancellor would by no means allow the two so much noted verses,

“Ready to pass to the American strand,”

to be printed; and Mr. Farrer would by no means allow the book to be printed and want them. But after some time, and some arguments for and against their being made public, the Vice-Chancellor said, “I knew Mr. Herbert well, and know that he had many heavenly speculations, and was a divine poet: but I hope the world will not take him to be an inspired prophet, and therefore I license the whole book.”

So that it came to be printed without the diminution or addition of a syllable, since it was delivered into the hands of Mr. Duncon, save only that Mr. Farrer hath added that excellent Preface that is printed before it.

If not pro-Puritan, the lines express a more general hope. Where the Puritans are going now, suggests Herbert, the rest of us might have to head before long.

King, Queen, and Bishop

That all seems clear enough, but why exactly was Herbert so panicked about the Catholic threat, and can we pin down an actual moment that occasioned this? One clue is that he does not cite Spain as the main vehicle for Catholic subversion, as would have been very common indeed around this time, but rather France. The obvious time for such a reference would have been after mid-1625, when the new king Charles I married Henrietta Maria, the devoutly Catholic daughter of the French king Henry IV. Henrietta Maria maintained her religion at the English court, and her circle of courtiers kept up a fervent Catholic culture that exercised real attraction for many Protestants. Charles tried to purge her French followers in 1626, but the queen became ever more influential after 1628, following the assassination of the King’s favorite the Duke of Buckingham. Thereafter, the tone of the court became ever more Catholic and Francophile.

In terms of dating, that French reference is vital: the poem cannot be before 1625.

The larger European context also matters. The queen’s brother was the French king Louis XIII (1610-43), a pioneer in the seventeenth century tradition of absolute monarchs. After 1624, he was ably assisted in this by Cardinal Richelieu. From the late 1620s, France was pushing forward its interests while other countries were weakened and diverted by the Thirty Years War. Although France did not intervene directly in the war until 1635, already in 1629, French forces won a significant victory in their war in the Duchy of Mantua, the War of the Mantuan Succession. That opened the door to expanded influence in Northern Italy and beyond, even to Rome. Or as Herbert warned, Seine might indeed swallow the Tiber.

Also in 1628, Bishop William Laud became Bishop of London, and occupied a pivotal role as the king’s adviser. Laud favored a higher sense of the church, which was far removed from what later became Anglo-Catholicism, but which alarmed and angered the Puritans. Laud’s power became greater and more visible in 1629, when King Charles ruled without Parliament, beginning his personal rule – and what later generations would call the Eleven Years’ Tyranny. In 1633, after Herbert’s death, Laud became Archbishop of Canterbury.

If Laud and the Laudians were in no sense crypto-Catholics, the combination of that political meltdown with the queen’s power at court made for an unsettling atmosphere for Protestants. Laud was looking uncomfortably like a local version of Richelieu. And we recall that this was all happening at the time of the worst Protestant setbacks during the larger Thirty Years War.

That was the essential background to the Massachusetts settlement, the chronology of which should be stressed. In 1628, the New England Company received its patent to settle Salem, and in March 1629, the newly renamed Massachusetts Bay Company received a new charter. That August, the shareholders signed a detailed plan in the Cambridge Agreement. The Winthrop Fleet sailed in April 1630, shortly after Winthrop outlined the “city upon a hill.”

The most plausible setting for the “Church Militant” would be somewhere in the 1629-30 era, when the Massachusetts venture was so much under discussion in and around the court; and when French influence was becoming so marked. As I will show, that was also a pivotal era in Herbert’s own life.

So we have in George Herbert someone who looks like what we might consider a very high church Anglican, who by rights should have been very happy with the Laudian reforms, but who conspicuously was not, and who wrote things that Puritans would have greatly relished. To understand this apparent mystery, we have to understand just who Herbert was, and where he stood in terms of his family and larger networks. The ideologies and factions resulting from those connections trumped personal styles, even in matters of religion. And as I will suggest, Herbert could be very interested in American matters without favoring Puritanism.

More on all this next time.

As this is quite a complex argument that will spill over into a couple of blogposts, I have put the whole thing together as a pdf that you can access by going here. It will download as a pdf of the full paper, which also contains quite a substantial bibliography. That should make for more coherent reading.