Between 2018 and 2020, Stacey Abrams helped register 800,000 new voters in the state of Georgia. Nearly half were people of color and nearly half were people under 30, both demographics that lean Democratic. As of this writing, President-Elect Joe Biden is winning Georgia by 14,000 votes. The last time Georgia voted for a Democrat for President was when Southerner Bill Clinton ran in 1992.

A single Black woman, Abrams rose to become Minority Leader of the Georgia House of Representatives in 2011, at only age thirty-seven. Abrams subsequently ran for governor six years later. She attributed her subsequent loss to Republican Brian Kemp, then Georgia’s Secretary of State, to voter suppression in Georgia. Prominent among the list of the state’s questionable actions included purging the registrations of citizens who had not voted in the previous two elections and decreasing the number of polling places. Both disproportionately affected Black voters.

Abrams responded in two ways: by filing a lawsuit against the state, and by founding a non-profit organization. That organization, Fair Fight, is the one that spent the last two years registering voters, educating them about voting rights, and advocating election reform.

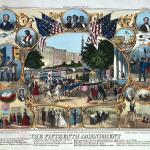

Faced with a political setback, Abrams pursued the grassroots politics of seeking out disenfranchised sheep and bringing them into the political fold. To forward her political vision, she worked to expand the number of people participating in the democratic process. Abrams stood in a long line of Black women who believed their faith demanded they work to make earth a little more like heaven and that the means to that end was expanding the electorate.

Historian Kathryn Nasstrom called attention to Black women’s work in voter registration in a now-classic 1999 article on a 1946 Black voter registration drive. The drive took place in the wake of a Supreme Court ruling that White primaries—one of many tactics Southern states used to suppress the Black vote—were illegal, and it took place in none other than Atlanta, Georgia. The drive succeeded in integrating Atlanta politics so well that Atlanta elected its first Black mayor, Maynard Jackson, in 1973.

In response, Nasstrom argued, histories of Black Atlanta political life came to focus on the predominantly male Black politicians who achieved office rather than the large number of female voter registration activists who helped put them there. For example, schoolteachers, predominantly female, embraced the drive, converted students to the idea, and through them, encouraged their parents to register.

Women’s participation in Atlanta community organizing and voter registration only grew with time. Nasstrom notes that when SNCC (Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee) undertook registration activities in low-income Black neighborhoods in Atlanta, they met the activists already present. In the words of one SNCC worker in 1966, “I have found that the women tend to be much more active there than the men.”

The question is why. Historian Charles Payne wrestled with this issue as he interviewed participants in the Civil Rights Movement. He found that by the 1960s, Black women in the Mississippi Delta were far more politically active than Black men—in terms of canvassing, attending meetings, and attempting to register to vote in an area with an abysmal Black voting rate attributable in no small part to threat of violence. He noted multiple possible reasons. Rural Black women were in the habit culturally of doing whatever needed doing and their activities were in general less subject to scrutiny by White society than those of Black men. Perhaps that would have made them less subject to reprisal. Yet reprisals often occurred against an entire family and Black women were by no means immune to beatings.

Payne argued that what motivated these women’s greater participation in the Civil Rights Movement was therefore a combination of their religious faith and their social networks, often also tied to church. He notes that, as is true of the American church at large, women made up the bulk of Black church members. The Black church often constituted the social and political center for the Black community during Jim Crow segregation and disfranchisement. Women convinced of the righteousness of civic organizing pulled in their friends. But even in more rural areas where the Black church proved more hesitant to participate, women more often believed their faith required that sort of concrete action.

The most dramatic case of a Black woman organizer motivated by faith was Fannie Lou Hamer. Historian Charles Marsh evocatively captures her story in God’s Long Summer: Stories of Faith and Civil Rights. In 1962, Hamer attended a Civil Rights meeting held in a church in Ruleville, Mississippi. She heard what was arguably one of the most successful sermons ever preached, became convinced that faith in Christ required working for justice, and volunteered to register to vote. She was brutally beaten in jail for her efforts, but never looked back. Hamer had no more than a middle-school education, but a natural talent for organizing and persuading and a powerful singing voice that rallied the community with hymns.

Hamer went on to help coordinate the successful voter registration drive known as Mississippi Freedom Summer in 1964. She then co-founded the biracial Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party—with another woman, Ella Baker—when the regular Mississippi Democratic Party sent an all-white delegation to the national convention anyway. The activism of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party was one of the forces behind the passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act fellow Anxious Bench blogger Chris Gehrz wrote about yesterday.

Stacey Abrams too learned political action from the church. Both her parents were Methodist ministers, and they encouraged her to live out her faith both inside and outside church walls. A young Abrams served as an usher and choir member, and joined her parents in soup kitchens and protests against South African apartheid. In 2020, Abrams partnered with local churches to ensure community members participated in the Census.

Black women have long experienced multiple layers of challenges in American society, and many have long looked to the church for meaning and support. Something about this combination has led them to tackle the problems of this world by doing the hard work of convincing other people to own their citizenship and join the quest. As a result, they have expanded democracy. We could all learn a thing or two from their approach.