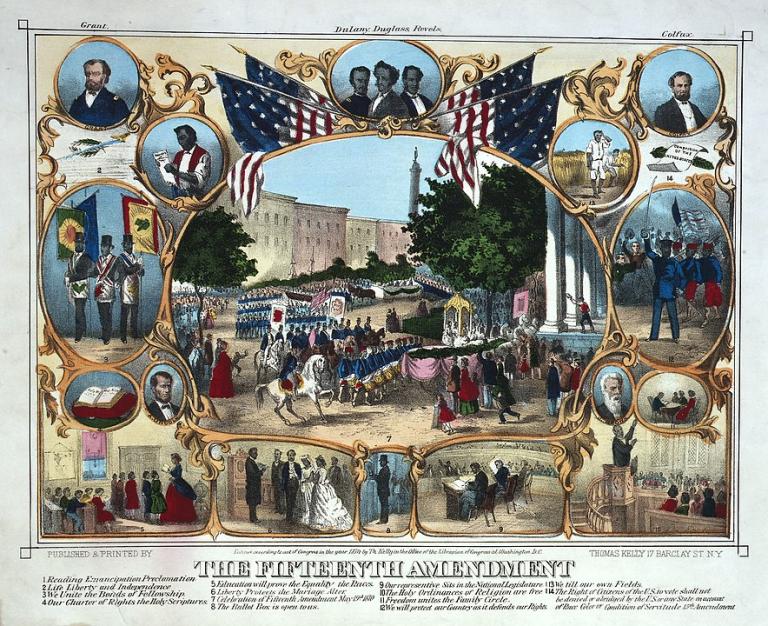

This past summer I wrote about the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment, which protects American women’s right to vote. But until last week’s election, it didn’t occur to me that this year is also the anniversary of another landmark in American democracy: the 15th Amendment.

But we’re being reminded this month that the story of enfranchisement — expanding the right to vote to all citizens — is intertwined with the story of disenfranchisement — taking that vote away. So before we go back 150 years, to the aftermath of the Civil War, let me first go back eighty, to another presidential election — and the troubling protagonist of my next book.

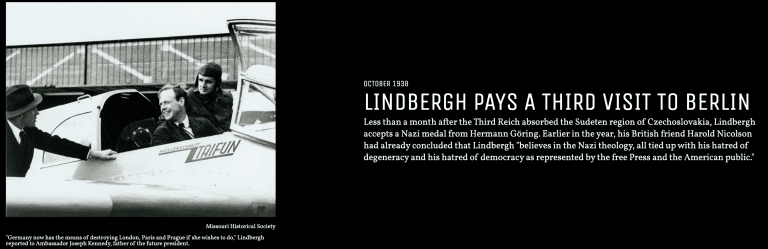

‘The indications,” Charles Lindbergh told his diary, “are that ‘democracy,’ as we have known it, is a thing of the past.”

It was the night of November 5, 1940, and the New York Times had just called the presidential election for Franklin D. Roosevelt. Just a week earlier, Lindbergh had aired his foreign policy differences with FDR at Yale University, in his first speech against American intervention in World War II for the new America First Committee. More speeches would follow in 1941, culminating in one where Lindbergh began, “I believe in freedom and I believe in democracy, but I do not believe in the form of freedom and democracy toward which our President is leading us today… Are we to die by the millions to make the world safe for the ideals of freedom and democracy that are denied to us in our own country?”

At least, that’s what he planned to say. But Japanese planes attacked Pearl Harbor five days before the AFC rally scheduled for Boston Garden. The undelivered speech was filed away, the United States did go to war, and Charles Lindbergh, hoping to reenter the military, had to go hat in hand to the same administration he believed had brought America to the brink of “a dictatorial system.”

Lindbergh had some reason to be bothered by FDR’s victory in 1940. Not only was an American president breaking George Washington’s precedent and seeking a third term, but Roosevelt had lied through his teeth just days before, pledging to a crowd (also in Boston, as it turned out) that “your boys are not going to be sent into any foreign wars.” Its own writer, Robert Sherwood, called that speech “terrible,” for FDR fully intended his nation to join the fight against Nazi Germany. The same night that Lindbergh proclaimed the demise of American democracy, the president quietly solicited the help of his Republican opponent, Wendell Willkie, a fellow interventionist who would spend the following year trying to convince Americans to support the British war effort.

Lindbergh was not a knee-jerk partisan. His ballot that day was mostly GOP, but his choice for governor of New Jersey was Charles Edison (Thomas’ fifth child), who had recently served as FDR’s navy secretary. But if he was willing to vote for one Democrat, Charles Lindbergh was no committed democrat. Not only did he believe that his country should make common cause with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy against “Asiatic Russia,” but he talked in private of stripping democratic rights from millions of his fellow Americans.

In a portion of his November 5, 1940 diary that he excised thirty years later from his published Wartime Journals, Lindbergh recorded a dinner conversation with his wife Anne and friends like the French surgeon Alexis Carrel. Here’s how Lindbergh reported the start of their conversation:

I said that I did not believe a political system based on universal franchise would work in the United States, and that we would eventually have to restrict our franchise. Everyone there agreed, and we spent some time discussing the principles upon which a restriction could be based.

Which Americans should lose their voting rights? The conversation soon turned to “the Jewish problem and how it could be handled in this country with intelligence and moderation.” The eugenicist Carrel added that only those with a “mental age of 12 or 14 years” should get to vote. For his part, Lindbergh made a suggestion that shows up at least once more in his (unpublished) journals:

I said that I felt one of the first steps must be to disenfranchise the Negro. Everyone agreed to this.

At that point it had been seventy years since the 15th Amendment guaranteed that the right to vote would not be denied to American citizens “on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” To historian Eric Foner, that third of the three Reconstruction Amendments was “a remarkable accomplishment given that slavery was such a dominant institution before the Civil War.”

But he added that the 15th Amendment’s history “also shows rights can never be taken for granted: Things can be achieved and things can be taken away.” Almost immediately, white supremacist groups like the Ku Klux Klan used violence to intimidate African American voters, and by the early 20th century, Southern blacks were functionally disenfranchised by poll taxes, literacy tests, and other devices. By 1940, less than 3% eligible to vote were able to do so.

So that November evening, Lindbergh presumably meant that he wanted “to disenfranchise the Negro” in Northern cities. Indeed, 1940 marked the first presidential election in which a majority of those black voters favored a Democrat for the office once held by Abraham Lincoln.

Even in the South, the tide was starting to turn against the likes of Lindbergh. A challenge to Texas’ white primary system in 1940 became an early opportunity for a young Thurgood Marshall and other NAACP lawyers to start reclaiming the 15th Amendment. The movement culminated in 1965, when iconic civil rights marches from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama led Congress to pass a Voting Rights Act, which President Johnson signed into law that August.

Fifty-five years later, about seven in eight African Americans cast their hard-won ballots for Joe Biden and Kamala Harris. Those votes clearly made a crucial difference in many battleground states, including Georgia, where Biden took the lead after counters went through ballots from Clayton County — home of Rep. John Lewis, who marched with King at Selma, watched with King when LBJ signed the Voting Rights Act, and died earlier this year.

In March 1965, the Selma marches ended with Martin Luther King, Jr., calling on “all of the freedom-loving people” assembled at the Alabama state capitol in Montgomery to “march on ballot boxes until race-baiters disappear from the political arena… until we send to our city councils, state legislatures, and the United States Congress, men who will not fear to do justly, love mercy, and walk humbly with thy God.”

Yet the race-baiter who currently occupies the Oval Office is refusing to recognize the ballots of his fellow citizens, and too many Republicans in the U.S. Congress are too afraid to do what is just, and stand up for democracy.

No democrat — Republican or Democrat — should tolerate the dangerous games Donald Trump and his enablers are playing with our system of government. Yet here we are, over a week after an election that yielded clear majorities for Biden in the popular vote (a higher percentage than Ronald Reagan’s in 1980) and the Electoral College, and Republicans keep echoing or indulging Trump’s baseless allegations of massive voter fraud. Even to the point of lambasting fellow GOPers who are doing a remarkable job overseeing fair and free elections in the middle of a pandemic. “There’s a great human capacity for inventing things that aren’t true about elections,” Ohio’s Republican secretary of state told the New York Times yesterday.

I hate sounding like an alarmist. I suspect that a week from now many more Republicans will have congratulated President-elect Biden and Vice President-elect Harris on winning what President George W. Bush has already called a “fundamentally fair” election with a “clear” outcome.

But in the meantime, we should not ignore the impact of nonsensical accusations of fraud, appeals to fabricated evidence, false pieties like “count every legal vote” (as if it’s tens of thousands of illegal votes that account for Biden’s margins), and reckless talk about having red state legislatures simply seat their own electors.

On the anniversary of mass enfranchisement, Trump and the Trumpists are promoting mass disenfranchisement. They seek to make the right to vote meaningless.

Stop saying "count every legal vote." It's a dog whistle that Trump and the right are using to get people accustomed to the entirely false idea that there is some large number of illegal votes that need to be discarded or rejected.

— African American Policy Forum (@AAPolicyForum) November 9, 2020

All Americans should be concerned, but once again, African Americans bear the brunt.

Let’s not pretend we didn’t understand what Donald Trump meant last week when he called for ballots not to be counted in majority-black cities like Atlanta and Detroit. In fact, so many of those votes were only able to be cast in the first place, Sherrilyn Ifill explained, because “it took a legion of civil rights lawyers, activists, and volunteers to combat egregious voter suppression tactics in order to make Black voters’ already hurdle-laden path to the ballot box slightly less cumbersome.” Capitalizing on a 2013 Supreme Court ruling that ended enforcement of a key provision of the Voting Rights Act, the Trump campaign has been acting to discourage and discredit African American votes. “This reality,” concluded Ifill, “should shame our country.”

If it doesn’t, if the 150th anniversary of the 15th Amendment proves to be the year that Americans sit by and let votes be made meaningless, then Charles Lindbergh will not only get his way about disenfranchising black voters, but he’ll finally be proven right: democracy, as we have known it, will be a thing of the past.