What does it mean that President Donald Trump visited a Ford factory last week, mentioned that company’s controversial founder, and commented: “Good bloodlines. Good bloodlines. If you believe in that stuff — you got good blood”? If you’re the head of the Anti-Defamation League, it means that the leader of the free world owes yet another apology:

Henry Ford was an antisemite and one of America's staunchest proponents of eugenics.

The President should apologize.

If he doesn't know why, our backgrounder on Ford's legacy will help:https://t.co/U3uxpdEDto https://t.co/0CdzCGLKvu— Jonathan Greenblatt (@JGreenblattADL) May 22, 2020

I’ll let a historian who has actually written a book on Ford’s anti-Semitism explain the meaning of Donald Trump’s apparent ad lib in the context of his presidency. I’m certainly no expert on Henry Ford or white nationalist dog whistling.

But I am working on a spiritual biography of Ford’s friend Charles Lindbergh. And even as Trump spoke last week, I happened to be writing about that famous flyer’s embrace of eugenics, which seeks to improve the human species by amplifying desirable genetic traits and eliminating others. That is, to promote “good bloodlines” and blot out others.

So, having often used this blog to think out loud about ideas before I started writing the book, let me now use it to test drive some of what I’ve been drafting.

I’ve blogged about eugenics once before, but that post mostly concerned Christian support for eugenicists like the Minnesotan physician Charles Fremont Dight, who certainly believed in “that [bloodlines] stuff.” Here he is in the Minneapolis Daily Star:

Just as a stream will be impure that takes its origins from a cesspool, so will the children be defective or diseased who spring from parents, both of whom have the same inheritable defects, or who, if not themselves defective, carry in their blood – the germ plasm — the determiners of inheritable disease or a morbid mentality; and this takes place no matter how much the parents may have been improved by education or environment.

Fresh off getting a 1926 law passed that eventually led to the forced sterilization of over two thousand Minnesotans, Dight tried to give Minnesota’s favorite son a medallion honoring “his superior hereditary endowment.” There’s no evidence that Lindbergh ever saw Dight’s honor in 1927, and he said nothing about his views on eugenics at that time. But let’s fast-forward ten years…

In October 1937 the Lindberghs were in their second year of living in England. Finally free from the press attention that had made his life miserable, the pilot had time to start writing more philosophical reflections on topics that ranged far beyond aviation. For example, he began to address a paper “to a minority of people…

to the men and women who are not willing to accept all others as their equals…. It is based upon the belief that individual character controls the trend and measures the quality of civilization, and that the richness of life is caused by differences and not by similarities. It challenges the doctrine of right based upon the quantity of men and advances the claim of right based upon the quality of men, and in opposition to the attempt to bring the spirit of man within the formulae of Science.

Eleven months later, in the middle of his efforts to lobby for Western appeasement of Nazi Germany — or even alliance with it, Lindbergh began to expand on that essay. Using religious language that would have seemed foreign to him a few years before, he refused to sacrifice “the quality of life” to the worst of all “idols set up by man,” the

false… god of equality. Men are not equal and should have no desire to be equal. The richness of life lies in its differences, and not in its similarities. A world of equal people would be like a desert of sand.

The doctrine of equality is a doctrine of death…. There is no equality in nature, in beauty, or in life. It is a concept of man, and not of God.

Lindbergh prefaced those comments with the proviso that he was engaged in “an attempt to clarify my own ideas. In the present stage, the writing is so incomplete that it may easily give a false, and in some cases opposite conception to that which I hold.” But if his thoughts were “incomplete,” he was right to worry: for anyone writing such a document in mid-September 1938 had to know that he might sound a bit too much like a German dictator in the midst of expanding his thousand-year Reich. Especially as Lindbergh continued his draft and started to defend inequality in explicitly racial terms:

Shall we submerge the spirit and life of Europe in the Yellow of Asia, or the Black of Africa? Or shall we stand with the Athenians at Marathon, unmindful of opposing numbers? Equal rights exist only among equal people — equal by their own nature, and not because they simply look similar to other men.

After a visit to Germany the following month, during which Hermann Göring awarded him the same swastika-emblazoned medal given to Henry Ford that summer, Lindbergh returned to his family’s new home in Brittany and continued writing his appeal “to a minority of people.” (It is unclear if he penned what follows before or after Kristallnacht, the vicious pogrom on November 9-10 that made even Lindbergh question the Nazis’ treatment of Jews.) He now began to articulate the importance of eugenics more explicitly than ever before:

Our primary concern must be the stuff of which man is made. The quality of children depends on the quality of their ancestors. Good heritage is mans [sic] most important and should be his proudest possession. It is on heritage that our Western Civilization is built. And on heritage it will stand or fall. This is the element which divides the European from the African and the Asiatic, which forms the intangible border between West and East. It is the strength of families and of nations; the difference between genius and mediocrity, (between) courage and cowardice, health and disease….

Now it is perfectly obvious that a high type of people will not result from indiscriminate marriage, or from the mixing together of all classes and races. We will not create better children by mating white with Negro, or by throwing America and Europe open to the Asiatic. On the contrary, we must choose with the utmost care. We must surround ourselves with people who add quality of mind and strength of body to our community, with people whose sons and daughters [blood] we are willing to have mixed [mix] with the blood of our children… Thus, and thus only can Democracy endure. (emphasis mine)

Now, it’s not surprising to find such a prominent American espousing such views in the first half of the 20th century. In 1901, for example, Stanford University president David Starr Jordan wrote a series for Popular Science entitled The Blood of the Nation: A Study in the Decay of Races by the Survival of the Unfit. (A year later those articles were published as a book by the American Unitarian Association.) In 1936 Anne Morrow Lindbergh’s first book, North to the Orient, was replaced at the top of the non-fiction bestseller list by Man, the Unknown, a strange, rambling book that decried the “demoralization and the disappearance of the noblest elements of the great races.” According to its author, Alexis Carrel, insanity, feeble-mindedness, and other “diseases of the mind” were “to be feared, not only because they increase the number of criminals, but chiefly because they profoundly weaken the dominant white races.”

“I keep thinking of Carrel’s book,” wrote Anne from the 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin, where Hitler had long since implemented eugenics. “Of what use is it? Is the emphasis correct? Is the spiritual and mental up to this? Or will it breed a race of tall soft-headed athletes?” But next to her, Alexis Carrel was the greatest influence on Charles Lindbergh’s spiritual and intellectual development.

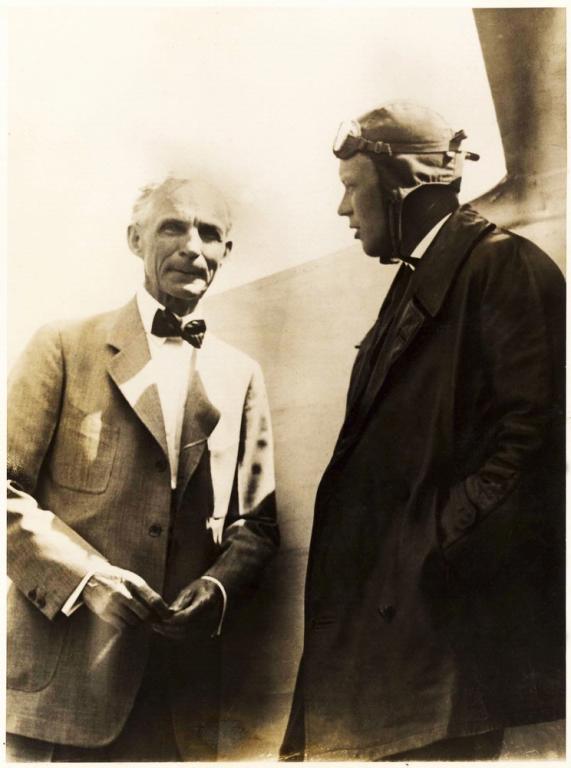

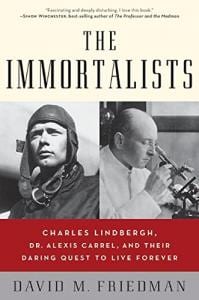

A French surgeon who won the 1912 Nobel Prize for Medicine, Carrel got to know Lindbergh in 1930, when the pilot started a second career as an amateur biologist. Using a pump designed by Lindbergh, Carrel kept alive tissues and organs for experimental surgery. (Their work was published in the journal Science.) But Carrel, a Catholic mystic who had studied the healing miracles at Lourdes, sought to take science beyond its modern boundaries. In Man, the Unknown, he encapsulated his ongoing efforts to achieve “a much more profound knowledge of ourselves” that would not reduce humanity “to a physiochemical system nor to spiritual entity” but instead fuse empirical, philosophical, and religious ways of knowing into a single “science of man.” Eugenicist Raymond Pearl (a biology professor at Johns Hopkins) praised Carrel’s book in a long review for the New York Times: “For probably the first time in history the Soul has taken a duly appointed place in a first-rate professional treatise on biology.”

A French surgeon who won the 1912 Nobel Prize for Medicine, Carrel got to know Lindbergh in 1930, when the pilot started a second career as an amateur biologist. Using a pump designed by Lindbergh, Carrel kept alive tissues and organs for experimental surgery. (Their work was published in the journal Science.) But Carrel, a Catholic mystic who had studied the healing miracles at Lourdes, sought to take science beyond its modern boundaries. In Man, the Unknown, he encapsulated his ongoing efforts to achieve “a much more profound knowledge of ourselves” that would not reduce humanity “to a physiochemical system nor to spiritual entity” but instead fuse empirical, philosophical, and religious ways of knowing into a single “science of man.” Eugenicist Raymond Pearl (a biology professor at Johns Hopkins) praised Carrel’s book in a long review for the New York Times: “For probably the first time in history the Soul has taken a duly appointed place in a first-rate professional treatise on biology.”

Such thinking had a profound impact on Charles Lindbergh, who began to place “less and less value on the mechanistic qualities of life.” But even as he absorbed some of Alexis Carrel’s fascination with the mystical and supernatural, he also adopted his mentor’s concerns about the “future of the race” that had built Western civilization. The more “spiritual, but not religious” he became, the more Lindbergh seemed to embrace the racialized worldview of eugenics.

In 1936-1937, Carrel sent his protégé drafts of a proposal for an “Institute of Man, or Institute for Human Betterment,” whose first goal would be the “use of voluntary eugenics in the building up of a stronger race.” From the study of everything from physiology to prayer, Carrel hoped to promote “the improvement of the spiritual and bodily state of the individual… For the quality of life is more important than life itself.”

This was the source of Lindbergh’s oft-stated interest in enhancing the “quality of life” — a concept that he wrote about in his 1937-1938 ruminations, and then for the rest of his life. Carrel’s Institute of Man never got off the ground, though he found support among wealthy businessmen like John Harvey Kellogg (whom Carrel credited with foreseeing “more than fifty years ago, the deterioration of the white races, which is evident today”) and, yes, Henry Ford, who offered the use of Ford Hospital in Detroit for Carrel’s research into “voluntary eugenics.”