Today’s guest post is by my friend and colleague Dr. Adina Kelley. Dr. Kelley earned her Ph.D. in 2019 from Baylor University, where she won the university’s Graduate Student Teaching Award. She then served as a full-time instructor in Baylor’s history department 2019-2020. This fall Dr. Kelley will begin a new full-time position as instructor of history at University of Northwestern – Saint Paul. Congratulations, Dr. Kelley!

As a college history instructor, the end of a semester brings a combination of relief and sadness as courses end and students move on from my classroom. Seasoned teachers know, however, that students permanently leave behind a piece of themselves, or more accurately, their opinions, in the form of course evaluations. These reviews can range from disparaging to glowing even within the same course section. Whether posted on a public site such as RateMyProfessors.com or submitted to the university as an official evaluation, multiple studies have shown that female and minority professors encounter significant bias when being reviewed by students. According to this research, simply being a woman or a minority faculty member can result in being docked up to -0.5 points on a 5 point scale.

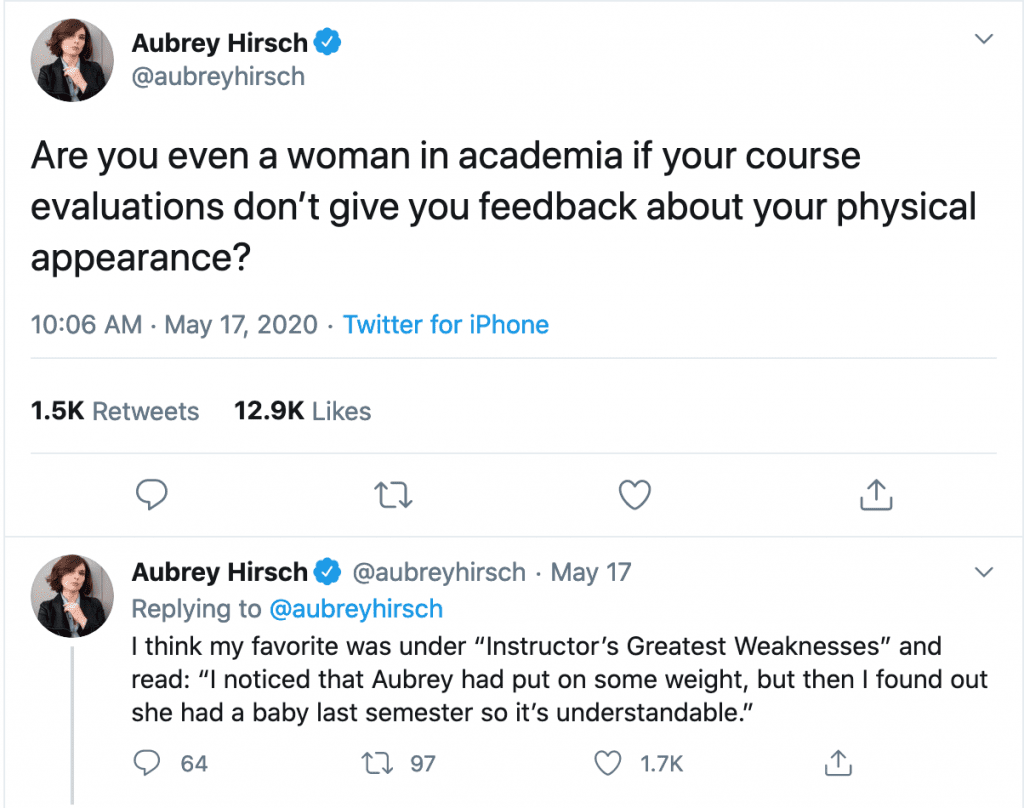

What this bias can look like on a practical level became apparent after Aubrey Hirsch posted this tweet:

The tweet garnered over three hundred responses, many from female academics sharing their own stories of how students had addressed their physical appearance in course reviews.

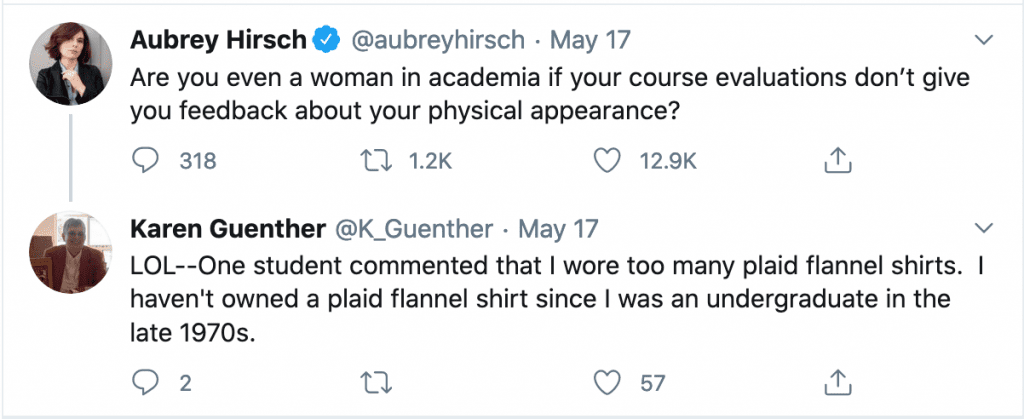

The stories ranged from humorous:

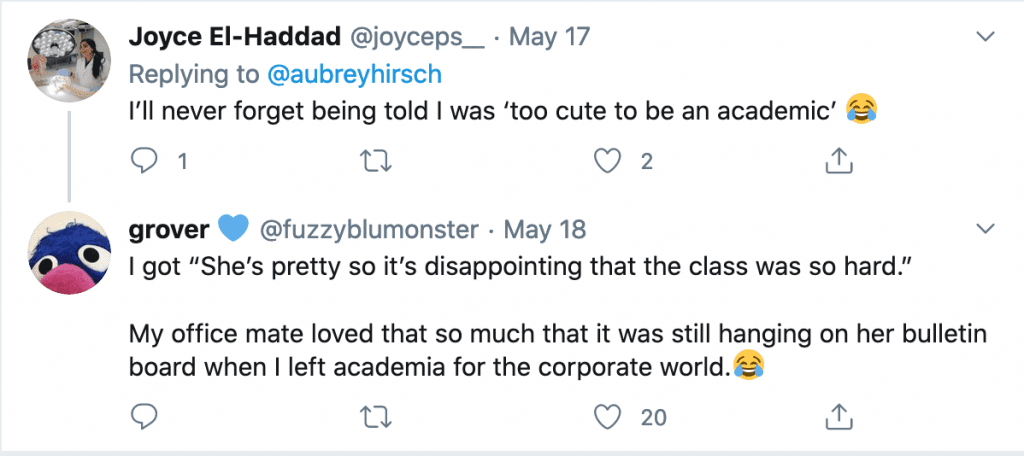

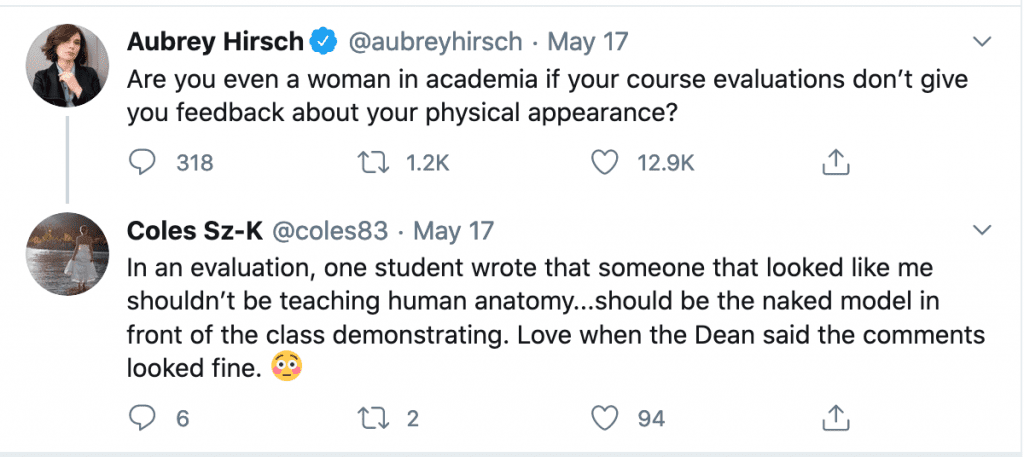

to concerning:

Since I have not personally had students comment on my body or clothing during my seven semesters teaching survey classes at Baylor University, and the majority of the responses to Hirsch’s post were from faculty at state or non-religious institutions, I became curious about my female colleagues’ experiences at Baylor and other Christian colleges. An informal survey of eight fellow female history instructors, ranging from Graduate Student Teacher of Record to Associate Professor status, showed a variety of experiences regarding mentions of physical appearance in course evaluations. Four had not had any students comment on their appearance, one had seen multiple “positive” comments about her clothing and one comment about her body type. Three professors had students negatively comment on their appearances, clothing and body, including changes experienced during pregnancy, which one student called “distracting.”

Though my survey is certainly not conclusive, it does show that appearance matters for many Christian students when evaluating female professors. My own research on evangelical ideals of femininity shows that Protestant women in the public sphere in the United States have long had their perceived competence tied to their physical appearance. One specific example of this phenomenon is women who take on the role of the “Minister’s Wife.” Kate Bowler recently published an excellent book on the role of female evangelical celebrities, including those she calls “preacher’s wives” since the 1970s. However, preacher’s wives were also a central part of evangelical culture during the 1950s, and like female professors, their physical appearance was noted by their congregants.

Though my survey is certainly not conclusive, it does show that appearance matters for many Christian students when evaluating female professors. My own research on evangelical ideals of femininity shows that Protestant women in the public sphere in the United States have long had their perceived competence tied to their physical appearance. One specific example of this phenomenon is women who take on the role of the “Minister’s Wife.” Kate Bowler recently published an excellent book on the role of female evangelical celebrities, including those she calls “preacher’s wives” since the 1970s. However, preacher’s wives were also a central part of evangelical culture during the 1950s, and like female professors, their physical appearance was noted by their congregants.

In January of 1959, the Conference of Ministers’ Wives of the Southern Baptist Convention sent out a press release to denominational magazines throughout the United States. The announcement asked for nominations for an award for “Most Outstanding Minister’s Wife,” stating that such a woman, “might be a musician, a writer, a teacher, or any Southern Baptist minister’s wife you feel has made the most outstanding and worthwhile contribution to the denomination.” As a result of these advertisements, over 175 letters from twenty-five states poured in, each letter explaining why its nominee was the ideal pastor’s wife.

Of these nominating letters, a significant number noted the physical appearance of their minister’s wife as an attribute that should make her more qualified to be “most outstanding.” Mrs. Carl Scott, of Central Baptist Church in New Mexico, was praised as “a very attractive brunette.” Of Mrs. Doris Moody, of First Baptist Church in Owensboro, Kentucky, it was said, “Her beauty is of soul as well as of face,” and “Besides being beautiful and charming, she possesses much talent.” But bodily appearance was not the only visual factor taken into account. Much like college professors today, it was expected that minister’s wives dress appropriately for their public role, and “appropriate attire” was determined by the eye of the nominator. Mrs. Tom Carmichael of Grand Avenue Baptist Church in Amarillo, Texas, was described as “a very attractive person, always simply though extremely well-dressed; neat, small in stature . . ..” Likewise, the nominator for Mrs. Helen Carpenter of Trinity Baptist Church in Albuquerque, New Mexico, exclaimed, “She dresses neatly and economically. Her appearance radiates her wonderful personality.”

While these are just a few of many examples, they illustrate the importance that physical appearance held for congregants evaluating the performance and effectiveness of their minister’s wife. Of course, much like college instructors, the minister’s wives were judged on many other criteria as well. Some measures directly related to their public roles, such as volunteer work and influence, and others less-obviously so, like the category the committee called “home loyalty,” defined as, “No neglected, much less delinquent, children,” or a “hungry husband, while mama shone before the WMU Exec. Board.”

Both my research and Bowler’s show that in mainstream and Christian culture, in 1959 and today, women are judged not just by their competence but also by their appearance. But it seems to me that Christian college faculty, both male and female, with their specific mission to build character or, in the case of Baylor, “create caring community,” have the opportunity to address this issue head on. Course assessments may give us a hint of the abilities of the instructor, but they often tell us even more about the character of the students. By educating students about the history of gender bias within mainstream and Christian communities and helping them to develop more thoughtful, appropriate, and respectful means of assessing temperament and ability, we can help them to grow in seeing the Imago Dei in themselves and in others. Course reviews can be a teaching tool not just for faculty looking to improve their teaching but also a means of identifying and addressing implicit and explicit gender bias in the academy and among Christians.