Public Domain, via The Times of Israel

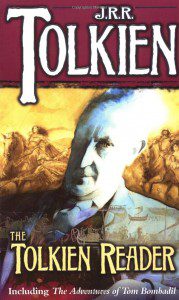

J. R. R. Tolkien in his famous essay, On Fairy Stories noted that a story is a spell, it has the magic to take you out of yourself and transport you somewhere else. He even pointed out that the gospel, etymologically speaking, is God’s spell. (The folks on Broadway picked up on that, if you recall.)

But a good deal of the preaching I hear leaves hearers where they are, trapped in themselves.

Most preaching feels more like literary criticism than a retelling of the greatest story ever told.

I think it has something to do with the tendency to merely report the facts, something I think the historical-critical method of interpretation lends itself to.

And even when preachers move on from that, they go straight to doctrine, or if they’re really into “applying the Bible”–life tips.

What this sort of preaching can’t do is help people trade in their scripts, or help them see the big story that that is being told all around them by God himself.

I had to learn to tell a good story the hard way

Actually, I’m not sure there is any other way to learn to tell a good story than the hard way.

I used to travel a lot preaching at youth camps and retreats around the country. I could tell a pretty good preacher’s story. You know, pull a tear from a dry eye, or get roars of laughter. And the stories always tied in nicely to points I was trying to make. So when I felt an urge to write fiction, a long and involved story, a novel, I thought I was up for the challenge.

I was wrong.

After trying my hand at it I could only produce reams of lifeless allegory. My characters were phony, my plots contrived, and my narration overbearing. I could only produce The Pilgrim’s Progress in new clothes, and the clothes weren’t very good.

So I did a lot of reading, got some impartial criticism, did a lot of re-writing. And finally, after a couple of years at it, I got the hang of it, good enough to win some small inconsequential awards and get into some third tier publications. I was even able to get the attention of some important literary agents in New York.

Here are some things I learned by trying to write a good story.

Honest characters make an honest story.

What’s an honest character? It’s a character who has a will of his own, not a cardboard cutout, something you can move around at will.

An honest character has motivations and goals, a history and fears. When you write about an honest character you have to ask, “What would she do in this situation?” You don’t make the character do things just because you need her to do them to keep the plot going in the direction you have predetermined. When you write honestly you discover things you could not have anticipated. Things tend to take on a life of their own. One reason so much so-called, “Christian fiction” is lifeless is because the characters have no life to speak of. They’re set pieces. In fact, the stories don’t even need to be told. nothing could possibly happen in them that would surprise anybody.

Anyone who reads this blog regularly knows I’m about as conservative as they come. But I knew I had nailed writing honest characters when I got fan mail from lesbians. I even got a note from a fan who lives in the sort of commune that should probably be burned to the ground. (Not that I would actually do that. I was employing hyperbole, you see. It’s a literary device.)

The best plots take the scenic route.

As honest characters pursue their goals in a good story, the plot weaves here and there. That’s why a good story almost always has a surprise ending; but it is almost always the inevitable ending at the same time. And in the hands of a Christian, it can be a good ending, a eucatastrophe, according to Tolkien–a joyous turn. But it is a happy ending that doesn’t elicit a groan.

For that to happen it can’t move in lock-step along the way, there needs to be a meandering quality to the story. (There can be foreshadowing, and there should be.) It’s this, along with honest characters, that make a work of fiction believable. That’s because this is the way our daily lives feel. They seem to meander pointlessly, just one thing after another, as we struggle to get along with, or fight, real people who have goals of their own.

How this all ties into preaching.

First of all, when you have mastered the art of telling a good story your own powers of interpretation will be more insightful. You’ll come to see narrative threads in scripture that were there all along, but you were just blind to. You’ll also find yourself stepping inside of biblical characters and seeing things from the inside out instead of the outside in. And you’ll recognize real people, not just cutouts that God moves around to make some doctrinal point.

(And you’ll see that the Bible is the book of the world, helping you to interpret the story that God is telling with the history of the world. And because the story hasn’t come to its end, even though we know it comes to a good end, you will be humbled by events rather than emboldened by them. That’s because good stories meander and take surprising turns. You’ll know you have no idea what is going on, even though you know the story will have a good ending.)

All this will help you connect with real people and their real lives. You won’t be able to impress crude, cookie-cutter interpretations on things people are going through. And you won’t feel you have the right to just push people around. You’ll more likely listen and wait and see. You’ll use words like, “maybe” or “could be”. After all, God is telling a story with us, and he’s not just pushing us around. He tells an honest story. But because he is the greatest story teller of all, we can be sure the ending will satisfy us, even though we can not possibly imagine how he will pull it off.