Public Domain, via The Times of Israel

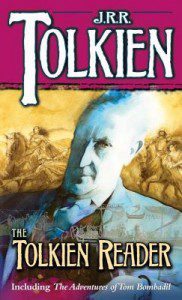

Leaf by Niggle is a personal favorite. It’s right up there with Smith of Wootton Major for me.

They’re two of Tolkien’s lesser works, but only if length is the measure. I think they’re distillations, densely flavored samples of the master’s mind. Smith embodies everything On Fairy Stories explicates in prose, the strangeness and melancholy of faire. But Leaf gives us something more personal, and a reason to hope.

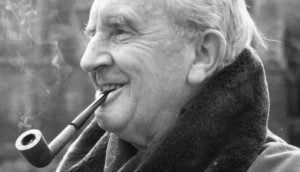

Everyone who’s read the story knows it’s about Tolkien. The protagonist Niggle is a niggler, something Tolkien called himself. Niggle is a painter whose ambition exceeds his skill. He allows his visions to run away with him, and he can’t seem to finish anything, or capture is visions to his satisfaction. He knows it will all come to an end eventually when he must go on a journey. We’re never told directly just where this journey will take him, but as we read we intuit that the journey is Niggle’s impending death.

Something that frustrates Niggle is the needs of his neighbor Parish. Parish is a clever name, alluding to a community–in Tolkien’s case probably Oxford as well as his actual church parish. He is always calling him away from his work. Not only that, Parish is a philistine, a man with a mind given entirely to practical matters, impatient with the painting (which he sees as a waste of time).

Niggle is torn, he knows that Parish makes legitimate demands on his time, but wouldn’t it be nice if the practically minded Parish would make a little room for painting? Well, to make a short story even shorter, he doesn’t, and then Niggle dies. And his paintings are forgotten.

But that’s only part of the story.

In our mundane-mundo Niggle is moved by a tree, a marvelous Tree. It’s what he wants to paint. He wants to get every detail right, each leaf, each glistening drop of dew. But when he dies his canvas is used to repair Parish’s roof, and even though a single fragment of it survives, a Leaf by Niggle, even that is lost eventually. And so the story ends, but only in this world.

In the world to come Niggle sees his tree again, more wondrous than he ever knew. Although it is never framed quite this way in the story, what arises in my mind whenever I read Leaf by Niggle is this: which is it, did the Tree appear in the world to come because Niggle saw it here, or did Niggle see it here because the Tree is already in the world to come before Niggle sees it?

I suppose I could be happy with the ending either way, but I have a feeling that this is more a matter of both/and rather than either/or. (There’s more to the story than this, it’s a densely flavored story, as I said.) But let me just distill a question for our consideration: “Do we have reason to hope that our works will be waiting for us after death, not only our good works, but our good work?”

Parish only thinks about good works. Parish is a philistine, after all, and all that matters to him is right and wrong. Something like beauty isn’t quite so important to him. For Parish pretty things are nice, but they don’t really matter. But for Niggle, and artists like him, beauty is the point. Even good works are meaningful because they’re beautiful (something upon which Von Balthasar and Jonathan Edwards agree).

The anxiety bubbling barely beneath the surface of the story is Tolkien’s fear that he may be wasting his life.

Leaf was written sometime between 1937 and 1942. (It was published in 1947.) But at that point the only thing published from the corpus we know today was The Hobbit. Things were not looking good for his true love, The Silmarillion, and Lord of the Rings languished. What would become of all this work?

Leaf is a self-administered consolation. But is that all it is?

We’re told in scripture that our works will follow us (Rev. 14:13), and that the kings of the earth will bring their tribute before the great king on the last day (Rev. 21:24). Are we talking only about ethics–works for which we will be rewarded? Is Mozart to be consigned to the flames?

I wonder.

Protestants like me are pretty quick to consign everything to the flames. It’s all stubble, vainglorious stuff. If it is tinctured with sin in the slightest degree, it’s worthless. But it that the case? Do our intensions lend our works their full meaning? There’s something modern about that, and vaguely gnostic.

Don’t we work with the materials God made and gave to us? And what about those flames, didn’t Paul say some things will pass through them purified? (1 Cor. 3:12)

I know what my Protestant friends are thinking right now, works! Yes, works. But let’s make sure the antithesis is the right one. Faith and works shouldn’t be confused. But grace is at work in our works if we are working by faith. (Perhaps that’s too parsimonious still.) Tolkien saw grace at work in his work. When Niggle sees his Tree for the first time what does he say?

“It’s a gift!” he said. He was referring to his art, but also to the result; but he was using the word quite literally.

Yes, he literally was. That’s the sort of literalism we could use more of. It would be an even more beautiful world if we did.