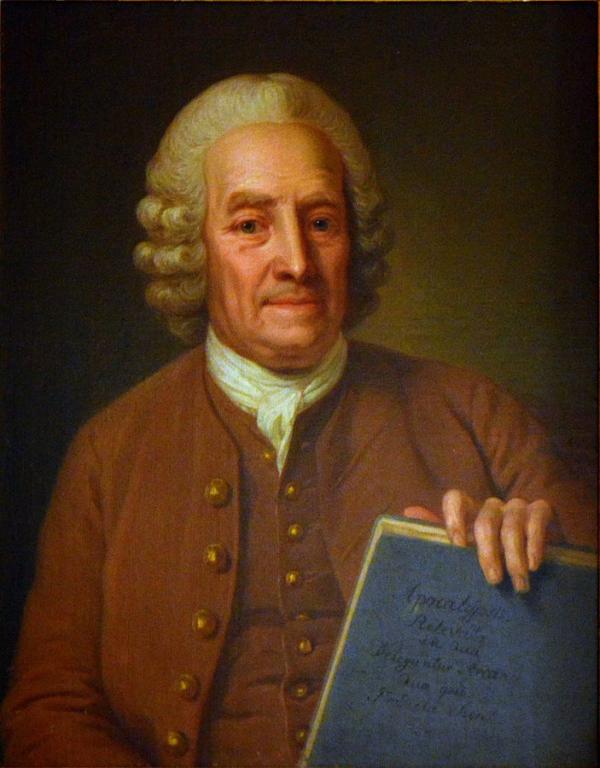

Yesterday marked the 330th anniversary of Emanuel Swedenborg’s birth (going by the Julian calendar, anyway). In my particular denomination of Swedenborgianism, our celebrations of Swedenborg’s birthday are more muted than they once were – we rarely any longer sing, “To Swedenborg, Our Wondrous Seer” (a real song, sung to the tune of “O Tannenbaum”). But blue and yellow Swedish cupcakes are still a common enough sight in New Church schools this week, and many talks and sermons this past weekend gave a nod to Swedenborg’s legacy.

As I’ve written before, those of us who believe in the Divine inspiration of Swedenborg’s theological works have a complicated relationship with Swedenborg the man. We insist, with Swedenborg, that he was nothing more than a servant of the Lord; but at the same time, we look for evidence that God was preparing him throughout his life for a special mission. It’s a worthy search, but one that sometimes results in a whitewashing of his life story.

Swedenborg was indeed a brilliant and talented man. But he also had faults. His scientific works contain theories and hypotheses that were not confirmed until centuries later. They also contain flights of fancy that are not supported by modern science. There is evidence that Swedenborg was a devout, charitable, hard-working citizen. There is also ample evidence that he was a little bit full of himself.

He wrote in a 1719 letter, for example,

“There are enough men in one century who plod on in the old beaten track, while there are scarcely six or ten in a whole century who are able to generate novelties based upon argument and reason.”

It does not take a great leap of imagination to suspect that Swedenborg numbered himself among those six or ten men.

I remember being taken aback when I first studied Swedenborg’s life in depth and noticed these hints of pride; I had apparently absorbed more hagiography than I’d realized. But the fact is, Swedenborg openly recognized this tendency in himself, and in his Journal of Dreams (written in the early years of his spiritual awakening), he wrote the following:

I saw a bookshop, and immediately the thought struck me that my work would have greater effect than the works of others, but I check myself at once by the thought that one person serves another and that our Lord has many thousand ways of preparing every one, so that every book must be left to its own merits, as a medium near or remote, according to the state of the understanding of every one. Nevertheless, the pride at once was bound to assert itself; may God control it, for the power in His hands.

A significant percentage of that journal is dedicated to Swedenborg’s wrestling with his own pride.

And I love this. I love seeing the puffed up language, the ornateness, the worldly ambition in Swedenborg’s early works and career. I love it for two reasons. First, because it punctures the kind of unhealthy hero-worship that can develop in any sect that admires a writer, try as we might to avoid it. Secondly, though, the style of Swedenborg’s later revelatory work is markedly different from the style of his earlier works – much more humble, and bereft of any self-important flourish. The evidence that he underwent painful changes to write those works is more compelling evidence to me of their truth than if they were a smooth evolution from his previous writings.

And so I say, here’s to Swedenborg, our wondrous seer – faults and foibles and all.

(Image by Per Krafft the Elder – Photograph: Esquilo, Public Domain, Link)