It’s nineteen degrees today, the lakes are frozen solid, and the snowdrifts are twice my height, but the sun is shining, and last night, it streamed through the kitchen window as I cooked dinner. My friends in Virginia say the daffodils are coming up. Meanwhile I’m positively giddy to have made it almost halfway through my first winter up north.

It’s nineteen degrees today, the lakes are frozen solid, and the snowdrifts are twice my height, but the sun is shining, and last night, it streamed through the kitchen window as I cooked dinner. My friends in Virginia say the daffodils are coming up. Meanwhile I’m positively giddy to have made it almost halfway through my first winter up north.

We moved to Northern Michigan in time for the worst winter in twenty years, the natives tell me. I don’t know any better, so I figured subzero temperatures and snow that hasn’t stopped falling since November—about one hundred inches so far—was just our lot. Everyone asks how I’m holding up. I’m okay. Nobody is more surprised by that than I am.

By Christmas break I was ready to flee. I had the car packed before Dave walked home from teaching his last class. I was worn out from two months of rib-wrecking bronchitis, early frigid cold, and terrible, wrenching homesickness. I couldn’t wait to see my family. For the first time since childhood, we’d all be together on Christmas Eve.

The ice and snow chased us all the way to Kansas. Our soft Thule car topper was frozen hard when we pulled into my sister’s driveway in Wichita, a day later than planned. We’d gotten stuck in Missouri overnight, and later ran out of gas less than twenty minutes from her house. We were exhausted and our car looked like Doc’s DeLorean after a round of time travel.

I had no intention of going to Christmas Mass. When our family of Catholic and Episcopalian children and ex-Catholic, fundamentalist evangelical protestant parents comes together, the Reformation happens all over again, and at this point in my life I will do anything I can to avoid the drama—including skipping a holy day of obligation. Besides, the weather was terrible.

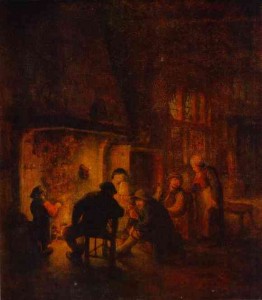

I voted for a homemade lessons and carols, planned by my little brother, who earlier in the year had announced he was gay and Episcopalian. I’m not sure which was harder for my dad. But surely this would appeal to our Mere Christianity—to read scripture and sing together. I also wanted to stay near the fireplace in my sister’s large and beautifully decorated house that looked to me, coming from faculty lodgings in the north woods, like something from The Nutcracker.

But those good Catholic children my sister and I have been raising were shocked when they overheard us talking about not going to Mass. But we have to! They protested. It’s Christmas! We immediately felt ashamed and ran to change our clothes, avoiding our dad’s eyes. The girls wanted to wear their beautiful Christmas dresses.

We arrived on time, slipping on the ice in the parking lot as we rushed for the door. In better weather, showing up merely on time would mean sitting in the school gym watching the Mass on television, but we easily found seats, filling in the last row. The priest came over and spoke gently to our children before Mass, smiling at our daughters, who made such a sweet picture, holding hands and whispering together. He seemed to take joy from their excitement, their anticipation of festivities and gifts, their happiness in the safe cocoon of love we’d created.

But there’s no way he could have known that. I’m projecting how I felt, enjoying Christmas more than I had in years, knowing what a gift we were giving them, the young cousins we’d always imagined would be so close but have seen each other less than once a year since their births. I always worry they won’t know each other—I remember painfully shy moments shared with my own visiting cousins in childhood—but each time they fly to each other with tight hugs.

Even my teenage nephews greet me with warm familiarity, and my niece, in fifth grade now, will spontaneously climb into my lap and let me braid her hair. We barely know each other in the superficial ways, and yet we know each other by heart.

In his homily, the priest spoke of the joy of children at Christmas, and how it is good and right. But, he said, if we find ourselves sad and lonely instead, as so many do at Christmas, perhaps this is right too. The joy of Christmas is only part of the story. There should never be a crèche without a crucifix nearby, he said. The baby comes into the world with a purpose, and that purpose is His passion.

Whether or not you believe in virgin births and angels singing in the fields and victory over death, there is no denying that every baby born on earth is headed for his own passion. Our most important job as parents is to prepare our children to endure.

Sorry—it didn’t seem so grim when Fr. Dan said it. I thought of what Rilke says in one of his letters to a young poet: “believe in a love that is being stored up for you like an inheritance…a strength and a blessing so large that you can travel as far as you wish without having to step outside it.” That’s what we should hope to give our children.

Normally such a homily would easily bring me to tears, but after being sick for three months and sick with longing for the green foothills of the Blue Ridge, I was not about to entertain morbid thoughts on this rare Christmas Eve. I’d just driven with my children for two solid days in the ice and snow and I didn’t want to imagine what any of our lives held beyond Christmas morning.

But I turned to see my brother crumbling in the pew. I tried to catch my sister’s eyes but saw she was crying too, and when my nephew turned to me his eyes were red and shining. My niece whimpered and my daughter buried her face in my elbow. None of us was crying for the same reason. Each of us, from eight to forty, had some private sadness or anxiety that the Mass drew out like an infection.

Later, by the fire, we went ahead with our homespun liturgy. We each took a turn reading, singing carols in between. I felt a rush of pleasure watching our children trace the words of the scriptures with their fingers, reading with such gravitas the prophecy of the light and the old tales from Luke about the baby in the stable. They made the ancient story new.

I watched my three-year-old son play quietly with his Legos, and my dad, equally distracted, leg bouncing and eyes far away, looking older this Christmas. “Seek out some simple and true feeling of what you have in common with them,” Rilke writes, “when you see them, love life in a form that is not your own.”

A gift to my children and to me, to step inside that kind of love again, to feast on it, to store it up, to carry it back through the weather.

Jessica Mesman Griffith‘s writing has appeared in many publications, including Image and Elle, and has been noted in Best American Essays. She is the author, with Amy Andrews, of the memoir Love and Salt, A Spiritual Friendship in Letters. She lives in Michigan with her husband and children.