WILLS POINT, TX – Gospel for Asia (GFA) Special Report on child labor today: Millions of Children Trapped between Extreme Poverty and the Profits of Others

Why Are These Children Working?

Many children work to survive, but it is a combination of perverse incentives and unjust business practices that creates the demand for child labour.

The Families’ Context

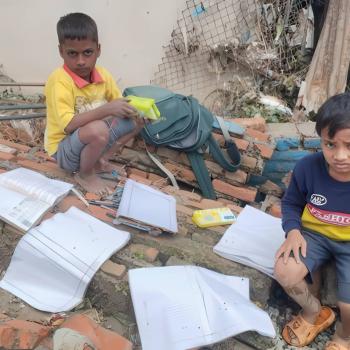

Families caught in generational or situational abject poverty are desperate. Some are suffering from the social inequities of the culture in which they live. Others have been displaced by war or famine and have no source of income at all. Either of these exacerbates the situation.

In many cases, the parents are illiterate and have no skills, and whatever jobs they have pay very little. These families are so poor and often in so much debt that they are not likely to recover from either without enlisting their children as breadwinners. They can see no way out of their poverty, so they sacrifice the future (the education and success of their children) on the altar of the immediate (survival now).

That resistance is not uncommon. A single child working in cotton fields can contribute as much as a quarter of the family’s income. Why would a family want to give up 25 percent of their income when it is already nearly impossible for them to meet their family’s needs for food, clothing and shelter? Their focus is on staying alive.

Partly to blame for their decision to send their children to work is their lack of understanding of the world outside their limited geographic sphere. They have little or no concept of the profits being made at the end of the supply chains that are linked to their hands and feet.

Remember Lukasa? On a good day, he makes about $9 mining about 22 pounds of cobalt. That’s $0.41 per pound. The market price of cobalt reached $80,490 per metric ton in 2018. That is $36.52 per pound or 89 times what Lukasa makes. On a good day.

These people live in desperate circumstances. Losing income will only make matters worse.

The Employers’ Context

Employers are responsible for generating a reasonable return on shareholders’ investments. It’s all about profitability. No business can continually operate at a loss. The highly competitive nature of international trade is predicated on getting products to market quickly, efficiently and at the lowest prices possible for consumers. Each level of the supply chain, from the top down, pushes the entire chain to reduce costs. The key for each link is to acquire at the lowest possible cost and to sell at the highest cost the market will bear.

152 million

children are in forced child labour

When businesses throughout the chain fail to manage this dynamic, they go out of business. When they succeed, the two links at the far ends of the chain suffer the most. The first-touch laborers are destined to subsistence wages or less, and the consumers expend more for the final product. There are no winners at either end of the chain.

Many employers maximize their gain from production by employing low-cost labor. Children are the least expensive labor; they have little or no bargaining power, and they are easy to manipulate. Because of the desperate status of millions of families in developing countries, unscrupulous employers take advantage of their willingness—or force them—covertly or otherwise to minimize their costs.

Other Obstacles to Ending Child Labour

Child labour is a well-known evil, and it is receiving global resistance. In Target 8.7 of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, member nations are obliged to take “immediate and effective measures to … secure the prohibition and elimination of the worst forms of child labour, including recruitment and use of child soldiers, and by 2025 end child labour in all its forms.”

UNICEF is the UN torchbearer for changing the cultural acceptance of child labour and offering “supporting strategies and programming to provide alternative income to families.” They expect to employ a multi-prong agenda, including legal reform; education; social protection; and access to health services in cooperation with other organizations, including corporate, governmental and NGOs, to accelerate child labour reduction in countries around the world.

Groups such as these are making headway in combatting child labour, but this global problem is not going down without a fight.

Obstacle 1: Lip Service

Maplecroft’s insights and analysis on Child Labour Index exposed the ease with which countries can and do pay lip service to the advancement of child labour eradication and other human rights. They simply sign a commitment that makes them acceptable in the sight of their peers but which they have no intention to keep. For that reason, successful eradication of child labour may be predicated upon the ability to “differentiate between the states taking appropriate action to stop child labour and those that are just paying lip service.”

Obstacle 2: Intransigence

Intransigence is being discovered within all levels of both government and industry.

Pakistan has ratified the Convention on the Rights of the Child and enacted laws to deal with eliminating child labor. However, an investigation launched by Dawn News discovered that the departments responsible for implementing those laws showed little or no concern about doing so.

Article 11 of the Pakistan Constitution states, “No child below the age of fourteen years should be engaged in any factory or mine or any other hazardous employment.”

Nonetheless, the Dawn report revealed that around 1.5 million children were engaged in labor work across a single province. The laws have been written. They just aren’t enforced.

In yet another incident, Human Rights Watch reported in 2016 that by the order of local officials in Uzbekistan, classes were cancelled and children as young as 10 years old were removed from school and sent to pick cotton.

As these examples illustrate, economic results were considered more important than the morality of employing child labor.

Obstacle 3: Limited Resources

Sometimes what looks like intransigence is simply a lack of resources.

Laws, regulations, mandates, goals, and agendas require resources to implement, monitor and enforce.

According to the Viet Nam News, “Vietnam was the first country in Asia and second country in the world to ratify the United Nations’ International Convention on the Rights of the Child.” Yet an estimated 1.75 million children are working in the nation. The labor inspectorate there is noted as “chronically underfunded and understaffed,” and if penalties are imposed, they often “amount to no more than a slap on the wrist.”

Tulane University professor William Bertrand has studied lofty aspirations, including federal and international mandates, and found that some—if not many—are “totally unachievable.” But it sure looks good on paper—especially to constituents.

From a corporate perspective, even if a company or entire industry budgets substantial financial outlays to prevent child exploitation as evidence of their “commitment”, that often does not reflect progress on the ground. One insider observed, “They talk a lot about the money spent on various activities related to child labor, but when we did the calculations, a fair proportion of that money was spent on sitting around and talking about it in London and Geneva.”

Funds spent on pontification in luxurious facilities have no effect on the places where they are most needed.

Included in the “most needed” is the ability to enforce laws where they exist.

Valiant Richey of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, told Reuters, “We can’t prosecute [cases of labor exploitation] fast enough. … The scope of the problem exceeds our ability to respond to it as law enforcement.”

250,000+

Krygyzstani children subjected to hazardous work

A 2018 study by the Kyrgyzstan Federation of Trade Unions (KFTU) found that implementing and enforcing are inconsistent at best. Although it had been 10 years since the country ratified the International Labor Organization convention for the elimination of the worst forms of child labor, more than 250,000 children were still subjected to hazardous work. The KFTU said the lack of ability to enforce the child labor laws is the greatest single obstacle to the elimination of child labor in the country.

Obstacle 4: Pushback

Unfortunately, this problem of pushback is as apparent in the United States as it is anywhere else in the world. In 2011, the Department of Labor (DOL) attempted to update the list of agricultural jobs dangerous for children under the Fair Labor Standards Act, but it was stymied by resistance from farm lobbying groups, including the American Farm Bureau.

The lobbying association reminded the DOL that “Farm Bureau advocates for the interests of farmers.” The powerful group is composed of farmers and related parties. Those delegates and their representatives seek to protect the farming industry, not to ban the employment of children on tobacco, cotton, or other farms. Farm lobbying groups say that restricting child workers in the agricultural industry threatens the fabric of American farms. Their position is that farms are generally family-run businesses. Evidence, however, suggests that child labor is more of a problem on large, industrially-operated endeavors.

When we understand that this is the nature of the beast in the United States, it should increase our awareness of the severity of pushback faced in developing countries.

Consider the case of Alternative Turkmenistan News (ATN) reporter Gaspar Matalaev. He is an investigative reporter working undercover to expose the state-run nature of forced and child labor during cotton harvests in Turkmenistan. Matalaev was arrested in 2016, two days after he published a report on the newspaper’s website about the state-orchestrated forced labor of children.

Refusal to contribute to the cotton harvest is considered insubordination, incitement to sabotage and contempt of the Turkmenistan homeland. Reporting on it is even worse.

Matalaev was tortured with electric shocks until he reportedly confessed to filing a fraudulent report. He remains imprisoned in a labor camp and is suffering from ill health as a result of the poor conditions.

There is pushback against attempts to eradicate child labor from the children and their families to the executive boardrooms, to the halls of humanitarian aid institutions, and to the highest national political offices.

Child Labor: Not Gone, but Forgotten: Part 1 | Part 3

Source: Gospel for Asia Special Report, Child Labor: Not Gone, but Forgotten

Learn more about the children who find themselves discarded, orphaned and abused, and the home and hope that they can be given through agencies like Gospel for Asia.

Click here, to read more blogs on Patheos from Gospel for Asia.

Learn more about Gospel for Asia: Facebook | YouTube | Instagram | Sourcewatch | Integrity | Lawsuit Update | 5 Distinctives | 6 Remarkable Facts | Media Room | Poverty Solutions | Endorsements | 40th Anniversary | Lawsuit Response |