I started this series as a way of addressing a common problem I’ve encountered throughout my career in documentary film making–our seeming inability to have constructive conversations about controversial topics. All too often, if someone refuses to accept our view on a given issue, such as hell, we walk away assuming some sort of moral, psychological or even spiritual defect on the part of the other. Why else would they refuse to adopt our position? Clearly some powerful force is blinding them from the truth.

What I’ve tried to demonstrate in this series is that even though stubbornness, ignorance, stupidity and/or insanity can play a role at times, more often than not, when two people of roughly equal intelligence and goodwill disagree, it’s not a matter of blindness. It’s a product of two people seeing the world in a completely different way. This doesn’t mean every perspective is equally valid or accurate. But if we’re to have any hope of evaluating our positions–much less agreeing on a criteria by which to make such judgments–we need to stop writing people off the moment our initial attempt to recruit them to our point of view fails.

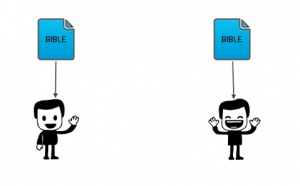

So let’s go back to my first diagram:

If this is how we think the world works, there’s really only one kind of conversation we can have:

If this is how we think the world works, there’s really only one kind of conversation we can have:

However, if we come to realize that none of us experience the world in such a direct fashion but rather through a complex set of filters, what I call an “Interpretive Principle,” all sorts of other possibilities open up.

This doesn’t mean we won’t still have conflicts. But once we back off from a totalitarian view of the truth–where the slightest provocation can offend and the smallest doubt can potentially undermine the coherence of our entire existence–differences of opinion are much less likely to engender malice, ostracism and violence.

What do these new kinds of conversations look like? For starters, behind every Interpretive Principle is a story. So perhaps that’s a good place to begin, by telling your story, and allowing others to do the same.

Telling your story is a great way to make sense of your experience, because it forces you to impose a narrative onto what, at the time, may have felt like a series of random events. Recounting how you arrived at your current set of beliefs also reminds you that you didn’t get here on your own. Your beliefs are the product of all sorts of influences, both internal and external, positive and negative. Furthermore, it will also become apparent that your beliefs have changed drastically over time. In fact, you will probably find that change, rather than stasis, has been the norm–which should give you pause whenever you’re tempted toward triumphalism. Telling your story also helps to reveal “holes in the plot,” so to speak, points at which you made certain assumptions or drew certain conclusions that no longer seem as valid when examined in hindsight or brought into the light for others to see. Finally, swapping stories also humanizes your conversation partner. You’re not simply sharing ideas; you’re sharing an experience. And I can’t think of a better foundation for friendship.

Now that we’re all arm-in-arm and singing songs around the campfire, perhaps it’s a good time to bring up the issue of criteria. We understand each other better now, but we still don’t agree. So what can we do about that? One option, as I’ve suggested before, is to forestall agreement in favor of friendship. We all have a limited perspective on the truth, so perhaps the best we can be is partly right. And maybe that’s good enough. But something about that notion doesn’t quite work for me. There must be some way of figuring out if we’re at least heading in the right direction, even if we don’t yet have the full answer. And yet it’s difficult to imagine a criteria that isn’t itself a product of a certain Interpretive Principle. Even so, I’ll give it a whirl.

In science, the best explanations are simple, elegant, testable, explain a wide array of phenomena and yield the most accurate measurements. Perhaps we can apply a similar criteria to arbitrating other epistemological disputes. So the best Interpretive Principle is the one that follows the law of parsimony, for example, the one that requires us to make the fewest number of assumptions. It should also have an aesthetic element, an inner beauty and coherence. And, finally, it should allow us to make predictions and then test them against the real world.

To my way of thinking, the criteria that best meets this description is a four-letter word: L-O-V-E. Love is simple, it’s beautiful and it’s easy to observe and experience its effects on the world. What is love?

Love is patient, love is kind. It does not envy, it does not boast, it is not proud. It does not dishonor others, it is not self-seeking, it is not easily angered, it keeps no record of wrongs. Love does not delight in evil but rejoices with the truth. It always protects, always trusts, always hopes, always perseveres. Love never fails. (1 Corinthians 13:4-8)

In light of this, evaluating our Interpretive Principle is rather simple. Does it make us patient? Kind? Forgiving? Trusting? Hopeful? A lover of truth? Or does it elicit envy, pride, selfishness, anger and vengeance?

If it’s the latter, perhaps it’s time we went back to the drawing board. If it’s the former, we still may not have the whole truth, but at least we’ll know we’re on the right track. And by all accounts, that’s the best we can hope for in this life.

For now we see only a reflection as in a mirror; then we shall see face to face. Now I know in part; then I shall know fully, even as I am fully known. (1 Corinthians 13:12)