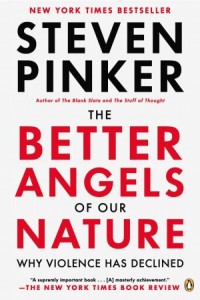

As Stephen Pinker argues convincingly in his book The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined, our sensitivity toward victims has increased substantially over the last several centuries, leading to a drastic reduction in violence. By way of example, it’s practically impossible today for any government, organization or individual to act in a discriminatory, aggressive or violent manner before before the global community blows the whistle and cries foul. This is particularly true when a huge power imbalance exists between the two parties. As soon as word of potential discrimination or abuse of power gets out, people rally around the victim and seek to shame the aggressor into backing off. This isn’t to say victimization doesn’t still happen. But Pinker assembles a mountain of data that demonstrates not only that the number of such incidents has decreased substantially over the past few centuries, even when such situations do develop, they don’t persist for nearly as long as they once did.

As Stephen Pinker argues convincingly in his book The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined, our sensitivity toward victims has increased substantially over the last several centuries, leading to a drastic reduction in violence. By way of example, it’s practically impossible today for any government, organization or individual to act in a discriminatory, aggressive or violent manner before before the global community blows the whistle and cries foul. This is particularly true when a huge power imbalance exists between the two parties. As soon as word of potential discrimination or abuse of power gets out, people rally around the victim and seek to shame the aggressor into backing off. This isn’t to say victimization doesn’t still happen. But Pinker assembles a mountain of data that demonstrates not only that the number of such incidents has decreased substantially over the past few centuries, even when such situations do develop, they don’t persist for nearly as long as they once did.

To what should we credit this growing sensitivity toward victims, and its commensurate reduction in violence? Pinker spends much of his book seeking to answer exactly this question. He credits the decline in violence to five main forces:

-

- The rise of the modern nation-state and judiciary, whose monopoly on the use of force helps prevent the threat of reciprocal violence between individuals

- The rise of “technological progress [allowing] the exchange of goods and services over longer distances and larger groups of trading partners,” so that “other people become more valuable alive than dead” and “are less likely to become targets of demonization and dehumanization”

- Increasing respect for “the interests and values of women.”

- Cosmopolitanism – the rise of literacy, mobility, and mass media, which “can prompt people to take the perspectives of people unlike themselves and to expand their circle of sympathy to embrace them”

- “The Escalator of Reason” – an “intensifying application of knowledge and rationality to human affairs,” which “can force people to recognize the futility of cycles of violence, to ramp down the privileging of their own interests over others’, and to reframe violence as a problem to be solved rather than a contest to be won.”

While I find Pinker’s insights extremely helpful, one of his major omissions is the work of Rene Girard and mimetic theory, which credits the gospel narrative (and the Hebrew and Christian Scriptures as a whole) for this shift toward non-violence. By revealing Christ, the ultimate victim, as innocent, the gospel exposes the sacrificial, scapegoating mechanism upon which culture is based, rendering it ineffective. We know too much about victims now, which is why it is so difficult to build a global consensus these days, even against someone as allegedly wicked as Osama Bin Laden. (For more on Girard and mimetic theory, David Cayley’s radio documentary for the CBC is a great place to start.)

No matter the cause, our growing sensitivity toward victims is a tremendously positive development overall. For those who believe in any sort of narrative regarding moral progress, this shift in attitudes towards victims is a hopeful sign. For those who scoff at the suggestion we are becoming less violent, once again, the credit for this skepticism must go to our growing sensitivity toward victims. Despite the solid data Pinker presents, many people see the world as growing more violent, not less. But this is partly because we are so sensitive to victimization that the slightest whiff of oppression sets us off. Incidents of violence or oppression that wouldn’t have merited a headline 100 years ago are now front page news.

Our perception is also skewed by the media–which is quick to pounce on victimizers, thus falsely magnifying the level of violence that is actually occurring in the world. The “shock and awe” factor is also at play. Even if our propensity toward violence is waxing, the means by which individuals or nation states can act on their violent impulses are more deadly than ever. Twentieth century tyrants like Hitler and Stalin are rightly villainized as some of the worst mass murderers in history. But think what Charlemagne or Ivan the Terrible or Robespierre or Nero would have done if they had the tools of mechanized warfare at their disposal.

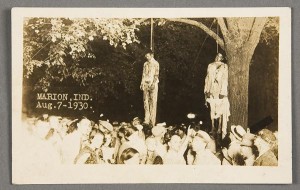

Speaking of the past, ignorance of history is another factor. We don’t have to look too far back in time to remember when aggressive attempts to take over neighbouring countries was not only expected, it was celebrated. Ever since World War II, however, such acts of aggression are condemned almost immediately, as we’ve seen with Russia’s recent exploits in Ukraine, Saddam Hussein’s foray into Kuwait, and America’s adventures in Iraq and Afghanistan. We also don’t have to think too far back to a time when lynchings in America were a public event, to the point people collected souvenirs from the victims and sold postcards like the one below. This wasn’t even 100 years ago. Yes, despite appearances, we’ve come a long way, baby. At least in North America.

Like any good thing, however, our sensitivity toward victims also has its down side. Things have reached the point that victimhood has become almost the highest virtue one can attain. Often, attaining victimhood status is akin to a form of moral purity, to the point where we think someone who has been victimized can do no wrong. However, in a cruel, ironic twist, these days claims of victimhood have become a precursor to violence and war. After all, who can question the actions of someone who has been dealt with so harshly? After everything they’ve endured, surely they deserve to live in peace and safety. By any means necessary. If this involves retaliatory or preemptive strikes against their enemies, so be it.

Like any good thing, however, our sensitivity toward victims also has its down side. Things have reached the point that victimhood has become almost the highest virtue one can attain. Often, attaining victimhood status is akin to a form of moral purity, to the point where we think someone who has been victimized can do no wrong. However, in a cruel, ironic twist, these days claims of victimhood have become a precursor to violence and war. After all, who can question the actions of someone who has been dealt with so harshly? After everything they’ve endured, surely they deserve to live in peace and safety. By any means necessary. If this involves retaliatory or preemptive strikes against their enemies, so be it.

In such an environment, “Never again” become two of the most dangerous words one can utter. Though originally coined to ensure an act of oppression was not forgotten, and to prevent similar situations from developing in the future, all too often “Never again” becomes a precursor to violence, to ensure never means never.

As a result, today we see conflicts, such as the current war in Gaza, that essentially amount to competing victimhood narratives, with people on each side vying for our sympathies. Hamas feeds the world nonstop footage and photos of dead civilians and devastated communities. Meanwhile, Israel wages its own propaganda war, playing up the evil deeds Hamas might carry out if their tunnels and weapons are not found and destroyed. As the body count piles up, outside observers dig in on one side or the other, ironically, all for the right reasons. People on both sides feel like they are standing up for victims. However, too often this defence amounts to little more than assembling evidence and arguments to justify further violence against their chosen victimizers.

Returning to Rene Girard and mimetic theory, if the gospel has shown us anything, it’s that the moment we find ourselves pointing the finger, the moment we find ourselves standing with the mob yelling, “Crucify him!”, we have departed from the way of Christ and joined his enemies. It doesn’t matter how convinced we are of our group’s purity and our enemy’s guilt–especially if we think we are pointing the finger on behalf of God–we are in the wrong. After all, the religious authorities of Jesus’ day were absolutely convinced of Jesus’ guilt and the threat he posed to their faith and their nation. In their eyes, Jesus wasn’t the victim; they were.

This is why we need to be extremely careful when confronted by situation where we’re asked to take sides–particularly on behalf of victims. As convinced as we may be that God is on our side and the side of our chosen victims, as Stephen Sizer asks in a documentary I co-wrote about Christian Zionism, “The real question we should be asking is not, ‘Is God on my side?’ but ‘Am I on God’s side?”

This is why we need to be extremely careful when confronted by situation where we’re asked to take sides–particularly on behalf of victims. As convinced as we may be that God is on our side and the side of our chosen victims, as Stephen Sizer asks in a documentary I co-wrote about Christian Zionism, “The real question we should be asking is not, ‘Is God on my side?’ but ‘Am I on God’s side?”

How can we know if we’re on God’s side? Simple. As Jesus says in Matthew 25 when speaking about the poor, “Whatever you do for the least of these, you do for me.” We tend to think of the least of these as those without power, the victims of this world, which is true. But more and more, I’m becoming convinced that those in greatest need of our love and empathy are not the ones who find themselves facing the barrel of a gun but also those whose finger is on the trigger. That’s right, I’m talking about our enemies.

As Marshall McLuhan once said, “All forms of violence are a quest for identity.” If this is true, and I think it is, those who practice violence are operating out of a tremendous lack, a deep, personal poverty that should elicit not our hatred but our empathy. Therefore, rather than mirror the violence of our enemies, we should mirror Christ, who never once adopted the perspective of his violent enemies and yet still managed to defeat them–not through destroying them but by transforming them into his likeness.

If we don’t walk this path, if we choose instead to continue down the road of violence, history has shown us that rather than be morph into the likeness of Christ, there’s only one person into whose likeness we will be transformed: our enemies.