My recent situation with Trinity Western University is a reminder of why I’ve always had difficulty with faith statements. On the one hand, I don’t think I’ve ever read a faith statement with which I can agree wholeheartedly. And I don’t think I’m alone in this. I often tend to disagree with myself mid-sentence, so that shouldn’t come as any surprise.

Therefore, when faced with the prospect of signing a faith statement, which I’ve had to do several times over my career, I’m left with two options:

1) Lie. Just sign the damn thing and don’t kick up a fuss. The problem is, lying is, well, a sin! Not only am I misrepresenting myself to the organization, I’m not being true to myself or my beliefs. So ultimately, it’s a cowardly, fear-driven act.

2) Offer a qualifying statement (or two or three). This is where the fear of scapegoating kicks in. The last thing you want to do within a creedal tradition is draw attention to yourself as some sort of an iconoclast. All eyes turn to you, wondering, “If he doesn’t agree with us on this point, what other seditious thoughts are circulating in that bald head of his?” From that point onward, if you aren’t expelled from the group outright, you are watched carefully in case you finally slip up and show your true colors.

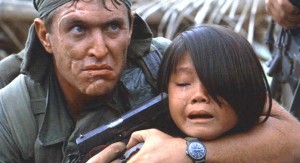

For such groups, conformity to the creed and perpetuation of the institution is paramount. The needs of various individuals within the group are secondary or tertiary at best, because they often see themselves as embattled organizations, under attack by the culture at large. Like an army in the midst of a firefight, summary expulsion is completely justified, because they simply can’t afford to have people running around doing their own thing. As Sgt. Barnes says in Platoon,  one of my all-time favorite films:

one of my all-time favorite films:

There’s the way it ought to be. And there’s the way it is… Now, I got no fight with any man who does what he’s told, but when he don’t, the machine breaks down. And when the machine breaks down, we break down. And I ain’t gonna allow that in any of you. Not one.

This is essentially how a fourth year Trinity student described the college’s current situation in an email yesterday when she urged me to simply accept the President’s decision and be quiet for the good of the school. How’s it going to look for us if we graduate from a college that is viewed as “narrow, provincial and fundamentalist” (as one of my friends put it)? In other words, shut up, because you’re making us all look bad.

So while I view this second option as far superior to the first, as I (and others) have discovered, it’s also much riskier.

Which leaves to my second problem with faith statements: To my way of thinking, Christianity isn’t about assenting to a set of propositions. It’s about following Christ. It’s not a statement of faith; it’s a way of life. It’s about loving God first of all, which frees us to love our fellow human beings, to practice self-sacrifice rather than demanding that someone be sacrificed for the sake of the group.

So rather than require prospective members to assent to a body of beliefs, which seems like a hyper-rationalist version of religion, if you’re going to ask them to sign anything, it makes more sense to request that they assent to a shared way of life, a way of living in community and relating to God and their fellow human beings.

Unlike a statement of faith, with brooks no compromise, a statement of community ideals or values is just that, an ideal. No one matches it perfectly, but no one realistically expects anyone is capable of doing so. Rather than serve as a pretext for scapegoating, a statement of values is a continual reminder that we all fall short of the glory of God every day. But we are united in our efforts to attain this ideal and to help others do the same.

I’m not saying scapegoating can’t also happen within such a context. We’re highly imaginative creatures, and outside of Christ, we know of no other way of forming an identity except through sacrifice of the other. So our first instinct is to bend everything toward some sort of scapegoating mechanism.

However, I still think inviting people into a shared way of living rather than demanding conformity to a set of beliefs presents a much stronger appeal to what Steven Pinker calls “The Better Angels of Our Nature.”