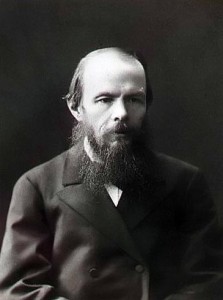

One of the most famous phrases to come out of Fyodor Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov is, “If there’s no God and no life beyond the grave, doesn’t that mean that men will be allowed to do whatever they want?” (phrasing from Andrew R. MacAndrew’s English translation). In other words, if human beings don’t have some kind of higher power to hold them accountable, won’t all hell break loose?

One of the most famous phrases to come out of Fyodor Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov is, “If there’s no God and no life beyond the grave, doesn’t that mean that men will be allowed to do whatever they want?” (phrasing from Andrew R. MacAndrew’s English translation). In other words, if human beings don’t have some kind of higher power to hold them accountable, won’t all hell break loose?

Not surprisingly, those who don’t believe in any sort of god or higher power have not only disputed the logic behind his statement, some have even denied that Dostoevsky ever said it–or that if he did say it, he didn’t actually mean it. (For the record, Ivan Karamazov did say it in the novel, but whether or not he was voicing Dostoevsky’s personal views is another matter.)

Their first line of defense is their own behavior–and that of other atheists and agnostics. As Richard Dawkins loves to point out, if you poll the religious views of most prisoners, you’ll discover atheists are by far the minority. Dilbert writer/artist Scott Adams comes at it a different way, arguing that there about 1 billion non-religious people in the world, and yet only about 8.75 million people are behind bars globally. That means 991,250,000 godless heathens should be running amok all over the planet right now creating chaos.

But that isn’t happening. In fact, most of the violence we see in the world today is motivated not by lack of belief but by some sort of religious or quasi-religious (i.e. patriotism, tribalism, ethnocentrism) conviction. Even so-called atheist regimes, such as the Third Reich, Stalin’s Russia or Mao’s Cultural Revolution, were beholden to quasi-religious ideals, with the state taking the place of God.

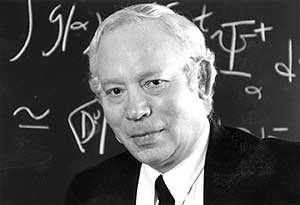

So, contra Dostoyevsky, it seems physicist Steven Weinberg got it right when he said, “With or without religion, you would have good people doing good things and evil people doing evil things. But for good people to do evil things, that takes religion.” To that I would add: “or at least something that closely resembles a religion.”

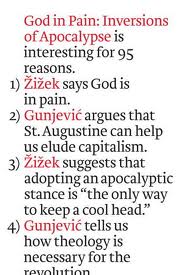

Indeed, Slavoj Žižek makes this very argument in his introduction to God In Pain: Inversions of Apocalypse,

Indeed, Slavoj Žižek makes this very argument in his introduction to God In Pain: Inversions of Apocalypse,

If God exists, then everything is permitted–is this not the most succinct definition of the religious fundamentalist’s predicament? For him, God fully exists, he perceives himself as his instrument, which is why he can do whatever he wants, his acts are redeemed in advance, since they express the divine will.

Interestingly enough, President Obama made a similar observation during his 2009 Nobel Peace Prize acceptance speech:

No Holy War can ever be a just war. For if you truly believe that you are carrying out divine will, then there is no need for restraint–no need to spare the pregnant mother, or the medic, or the Red Cross worker, or even a person of one’s own faith.

Put another way, if we believe that God exists, and that we are his/her/its agents on earth, then anything God permits is permitted for us as well. Maybe this is why A. W. Tozer said, “What comes into our minds when we think about God is the most important thing about us.” For if the God we believe in permits war, genocide and the like, what is to prevent us from carrying out such actions in his name?

Lest you think I’m being too hard on religion, let’s back up a moment and reexamine Obama’s use of the term “Holy War.” My question is, is there any other kind of war? As Yale Law School professor Paul Kahn asks in his book Political Theology: Four New Chapters on the Concept of Sovereignty, “What else but a religious commitment could make the [nuclear] destruction of the world even thinkable? What else could justify the sacrifice of soldiers in war?” Whether one is fighting for God or a state, the sacrifice demanded is the same–blood.

So perhaps we need to revise Dr. Weinberg’s quote further to say,

So perhaps we need to revise Dr. Weinberg’s quote further to say,

With or without belief in a higher power–be it a god, tribal or ethnic group or sovereign state–you would have good people doing good things and evil people doing evil things. But for good people to do evil things, that takes belief in something greater than ourselves.

If this is true, that puts all of us–religious and non-religious alike–in a bit of a pickle, because everyone’s identity is nested within familial, ethnic, racial, national and religious or philosophical structures. When one or more of those structures is threatened, it’s only natural to rise up in defense and sacrifice the lives of others or even our own lives on behalf of what we perceive to be the greater good–never mind the fact our enemies feel exactly the same way about defending their own institutions and way of life.

Thankfully, Obama’s Nobel Prize speech doesn’t end there. He goes on to say,

Such a warped view of religion is not just incompatible with the concept of peace… it’s incompatible with the very purpose of faith–for the one rule that lies at the heart of every major religion is that we do unto others as we would have them do unto us.

I’m not sure if I completely agree with Obama’s argument here. It seems a little too “implurialistic” for me–never mind the fact his administration has behaved in ways that completely disavow not only this statement but virtually every other principle he expounded in his speech. However, I definitely agree that recognizing our shared membership in the overarching structure of the human race is a good place to start.

I’m not sure if I completely agree with Obama’s argument here. It seems a little too “implurialistic” for me–never mind the fact his administration has behaved in ways that completely disavow not only this statement but virtually every other principle he expounded in his speech. However, I definitely agree that recognizing our shared membership in the overarching structure of the human race is a good place to start.

Then it’s only extra-terrestrials who’ll have something to fear…