Concord was a small town during the time of the Transcendentalists, and it’s still a small town today. A whiff of Old Money lingers in its air, and though there are certainly tourists in Concord, the town seems to have a somewhat ambivalent relationship to them, encouraging them to visit but not totally rolling out the welcome mat.

While its downtown can be crowded with visitors, its residential streets give the best sense of the true Concord—genteel, discreet, and dignified. Picket fences guard stately homes that bear plaques proclaiming the dates they were built and the names of their distinguished former residents.

Many visitors come to Concord to visit the Minute Man National Historic Park, which preserves the site of the first battle of the American Revolution on April 19, 1775. But I would guess even more come to town because of Concord’s connection to some of the best-known writers in American history: Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, Louisa May Alcott, and Nathaniel Hawthorne.

Concord, in short, is a place that reduces English majors to quivering, hyperventilating groupies.

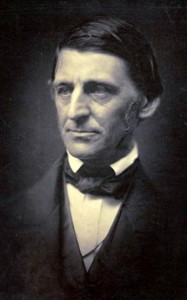

That said, visiting Concord requires a bit of imagination. One needs to know something about the authors who once walked its streets to fully appreciate the town’s significance. Of that distinguished set, it was Emerson who was the great celebrity of his day—you could say, in fact, that he was the literary equivalent of a rock star, lionized and admired throughout the nation.

Emerson had grown up in Boston and became a Unitarian minister after attending Harvard Divinity School. His first marriage ended tragically when his wife died of tuberculosis at the age of 20. Emerson was devastated by her death, which triggered a crisis of faith that exacerbated the doubts he was already having about the doctrines of the church. In the words of Susan Cheever, author of American Bloomsbury, Emerson turned instead to find “spiritual solace in other people, in the natural world, and in his own breaking heart.”

Supported by the money left to him in his wife’s estate, Emerson remarried, settled in Concord, and began to write essays and poems that eventually made him the most influential thinker of his day. In 1840 he founded The Dial with pioneering feminist Margaret Fuller, a magazine that published many of the most important writings of the Transcendentalists. His best-known essays often began as lectures, discourses on topics such as self-reliance, love, friendship, and heroism.

While he was famous in his day—no doubt helped by being tall and handsome, with a resonant baritone voice—Emerson’s star as a writer and thinker declined after his death. His most lasting legacy is the literary community that he helped form in Concord. One gets the sense that Emerson enjoyed conversation so much that he was willing to do almost anything in order to have kindred souls around to talk to. He issued invitations to like-minded folks, luring them to Concord with offers of assistance, and it was his wealth that often kept the rest of the literary crew afloat. (Louisa May Alcott recalled that when Emerson came to visit her family, he often left a stack of bills tucked discreetly under a plate.)

Those who wish to pay their respects to Emerson should visit the home where he lived for nearly 50 years. Another major site is the Concord Museum across the street, which has a room that contains the contents and furnishings of his study as it was left at the time of his death. This time capsule preserves what was once the epicenter of intellectual life in America.

But really, Emerson’s most significant legacy is the set of books written by his friends, volumes that exist in part because of his generosity. Without him, we wouldn’t have Walden, in particular, and for that masterpiece alone posterity surely owes Emerson lasting thanks.

Much of Emerson’s work has a musty quality to it, seeming wordy and over-written to modern ears. But his words on friendship still resonate, especially because we know that he practiced to the fullest what he preached: “When friendships are real,” he wrote, “they are not glass threads or frost work, but the solidest things we can know.”