I live in Iowa City, Iowa, home to the famed Iowa Writers Workshop, the nation’s oldest and most respected creative writing program. Over the years I’ve known a number of workshop graduates, and I’ve frequently been amused by their black humor as they talk about tragedies in their lives. In the literary world, having something awful happen to you or your family is a big plus, for it provides a rich vein of writing material. The more unusual and tragic, the better.

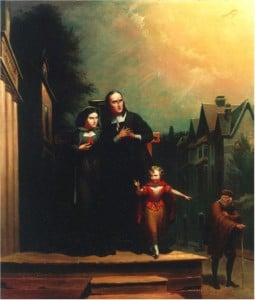

If having something dark in your past is an asset, Nathaniel Hawthorne hit the jackpot. Hawthorne grew up in Salem, Massachusetts, the site of the notorious witch trials of 1692-93, when 20 innocent people were executed as a result of hysteria, ignorance, and religious intolerance. What’s more, his ancestor William Hathorne had been one of the presiding judges (Hawthorne added a “w” to his name, perhaps to distinguish himself from his hated ancestor).

All of this provided Hawthorne with a wealth of material indeed. While his fellow Concord luminaries were idealistic Transcendentalists, confident of the perfectibility of humans, Hawthorne became the dark muse of the Puritan soul, exploring its limitations, strengths, and complexities with keen psychological insight.

Hawthorne was a shy recluse in his early adulthood, but eventually married a woman who was a follower of the Transcendentalist movement. The newlyweds were invited to Concord by Emerson, who helped them rent a house known as The Old Manse.

Though he had some initial successes as a writer, after three years Hawthorne had to return to his hometown of Salem because of mounting debts and financial difficulties. There he became a customs inspector at the port, a position that he later lost because of political reasons. Unemployed, in mourning for the death of his mother, and desperately sad, Hawthorne began to write The Scarlet Letter, a tale of adultery and intrigue in a seventeenth-century Puritan town.

When it was published in 1850 the book became a best-seller, but the people of Salem were far from happy at what had been created in their midst. The book forced them to reflect on the ways in which neighbor can betray neighbor and fear can poison a community, just as had happened during the Witch Trials. While the story of the sympathetically portrayed adulteress was outrageous enough to the proper townsfolk of Salem, they were also incensed by the book’s introduction, which many took as an insult.

“If I escape town without being tarred and feathered,” Hawthorne later wrote to a friend, “I shall consider it good luck.” He and his wife returned to Concord in 1852, where they bought Hillside, the home formerly occupied by the Alcott family. The next year they would leave once again after Hawthorne was appointed U.S. consul in Liverpool, England (a plum appointment courtesy of his friend, President Franklin Pierce).

Though friends with his fellow Concord authors, Hawthorne’s outlook on the world was fundamentally different from that of the Transcendentalists. “Eager souls, mystics and revolutionaries, may propose to refashion the world in accordance with their dreams,” he wrote, “but evil remains, and so long as it lurks in the secret places of the heart, utopia is only the shadow of a dream.”

I found myself surprisingly intrigued by Hawthorne during my time in Concord, though his imprint on the town is much less than that of Emerson, Alcott, or Thoreau. In many ways I prefer the sunny idealism of the Transcendentalists, but in the end, I think that perhaps Hawthorne had the deeper insights into the workings of the human soul. Having an ancestor who was a judge at the Salem Witch Trials will do that to a person, I suspect.

And such a writer he was! I leave you with another quote, this from “The Haunted Mind” in Twice-Told Tales:

“In the depths of every heart there is a tomb and a dungeon, though the lights, the music, and revelry above may cause us to forget their existence, and the buried ones, or prisoners whom they hide. But sometimes, and oftenest at midnight, these dark receptacles are flung wide open. In an hour like his….pray that your griefs may slumber.”