Today’s post is the third in a series on The Story of God With Morgan Freeman. I wrote this after previewing this Sunday’s episode, “Creation.” You can watch it on the National Geographic Channel, or on the National Geographic app beginning the day after it airs on TV.

To me the most interesting statement in the “Creation” episode comes at the very beginning, when Morgan Freeman visits his hometown in Mississippi and says, “You can’t understand me until you understand where I was created.”

That statement gets to the heart of why creation stories are important, whether they’re on a cosmological scale or a human one. How we tell our story of origin shapes us, and shapes how others see us.

I can tell you this about myself: I’m a farmer’s daughter from Iowa. And even though I’ve left that life behind in many ways, it still defines a good portion of my identity.

This brings to mind a trip I took to Galilee several years ago. At a certain point on the journey I realized there were parts of the story of Jesus that I simply hadn’t gotten before—why he used all those metaphors about sheep and vineyards, for example, and why the Sea of Galilee plays such a large role in the Gospels.

It was like being in college and going to the home of a roommate for the first time and realizing, “Oh, that’s why she’s the way she is.”

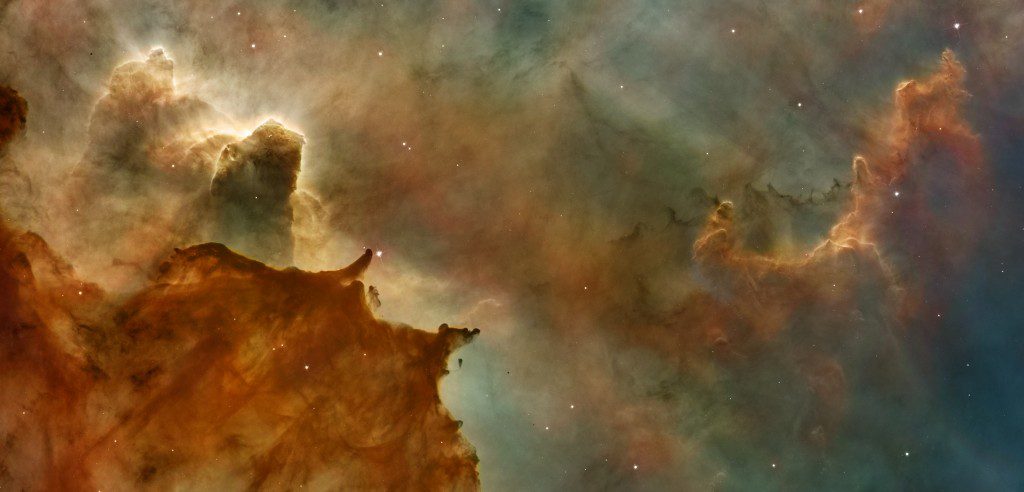

Cosmological questions, even more than individual stories of origin, always raise profound questions of identity and meaning. In the “Creation” episode, I loved the urbane Vatican astronomer who brushed aside any conflicts between the Genesis story and scientific theories of creation. It’s simply a non-issue, he says. Of course Christianity is compatible with science. Case closed.

But the Genesis account of creation (which includes strains from at least two different traditions) says several things that became foundational for Western culture: The universe makes sense. It unfolds in an orderly fashion, one that can be comprehended by humans. And it is good, for God shaped and formed every part of it. With that as a foundation, you can pile on biology and physics and astronomy and all sorts of other scientific disciplines without fundamental conflict.

That said, I must admit to not thinking very much about how the world was created. The writers of Genesis might be right, or the Hindus might be correct in saying that the universe was created and destroyed many times. However it happened, it probably involved a Big Bang of one sort or another.

But in recounting these stories, whether they’re told from a pulpit or in a scientific textbook, we claim something as humans: we assert our right to try to understand our world. And I think God sees this and smiles, for he wants us to struggle with these questions.

All of this makes me think of one of my favorite Bible stories, that of the long-suffering Job. Contrary to the popular saying that refers to “the patience of Job,” he was anything but patient—in fact, if ever there was a questioner, doubter, and complainer, it was Job. After overwhelming tragedies have befallen him, he rejects the facile philosophies of his friends and demands an answer from God himself.

And how does God respond? He answers Job with a creation story. He talks about creating the storehouses of snow and hail, of setting the stars in the sky and releasing the eagles to soar and the horses to race.

In one sense he doesn’t answer Job’s questions at all. But he also doesn’t say that Job shouldn’t be asking them.

For it is the nature of humans to question, and it is the nature of God to create. And sometimes the best answer to “Why?” is a show-and-tell: a starry night high in the mountains. The beauties of a coral reef under the sea. Flowers blooming in the desert after a rain.

For all of these are good, whenever and however they were created.

Stay in touch! Like Holy Rover on Facebook: