For much of my adult life I’ve been a wannabe meditator. But even with good intentions and periodic resolutions that this-time-it’s-going-to-be-different, I could never keep a practice going for more than a few days. It all sounded so good in theory, but when it actually came time to sit with my eyes closed, trying to clear my mind of thoughts, I instead thought about an endless stream of thoughts that needed to be thought about right now.

And then Andy came into my life.

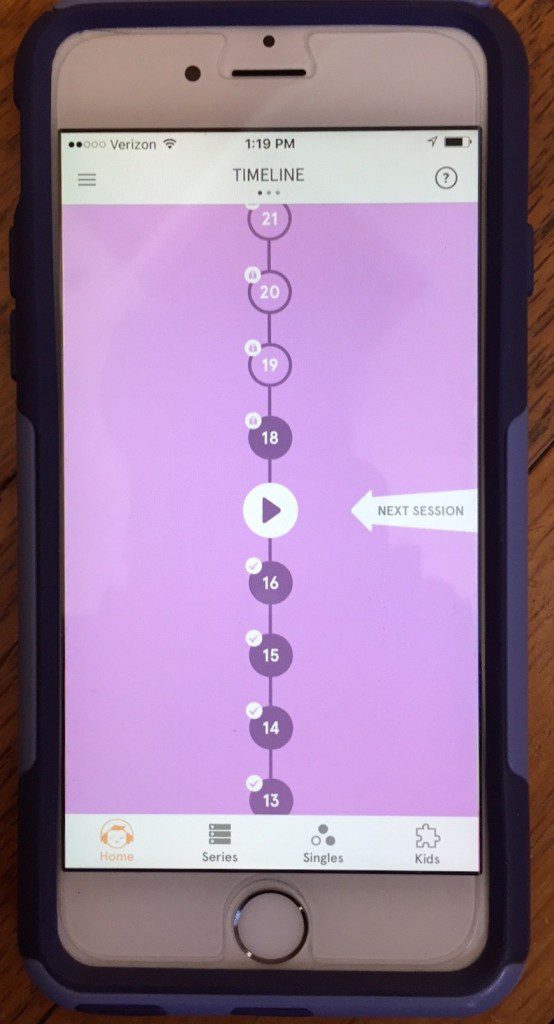

Andy lives inside my smart phone. He has another existence as well, I realize, but for my purposes he lives inside that little handheld device, ready for me whenever I need him. And I’ve come to rely on his gentle guidance given through a humble phone app (if you want to try it yourself, go to Headspace). Perhaps it’s the combination of the technology (“you’ve meditated for 10 days in a row—good job!”) and my over-50 stage of life that have finally given me some commitment to the practice of meditation.

To my embarrassment, after a few months I’ve become one of those people who keep bringing up meditation in conversation, extolling its benefits and urging people to try it. I take some comfort in the fact that this is more socially acceptable than being a born-again Christian (at least in my social circle), but born-again meditators can have a similar sense of evangelical zeal. I’ve discovered this amazing thing—don’t you want to hear about it?

The problem is that the insights that seem so significant when my eyes are closed don’t attract much interest from anyone else. “In my meditation this morning I was obsessing about something and then I had this great moment when I just let it go,” I told Bob.

“And?” Bob asked. “What happened next?”

“I just let it go,” I repeated, a little peeved that he didn’t recognize what a breakthrough this was.

“Good for you,” he replied, and then asked what else needed to be put on the grocery list.

Andy often gives me metaphors to help explain a concept, including one that says thoughts are like boats passing by on a river. You’re supposed to look at them pass by, but not catch a ride on them.

Sometimes, I must admit, I ride one of those boats for quite some time, and my meditation time is just an excuse for daydreaming. But sometimes-—often enough that it keeps me meditating—-I experience something else: Stillness-with-a-capital-S. There’s a kind of weightlessness about this state, a clarity of heart and mind that almost shimmers.

And more and more when Andy’s soothing voice tells me my session was over, I’m surprised, as it feels like I’d been mediating for only a few minutes. It gives me a glimpse of what it would mean to have that internal, ceaseless dialogue turned off, or at least toned down.

My budding meditation practice gives me glimpses of the architecture of my mind. It isn’t a grand cathedral, alas—more like an attic with lots of nooks and crannies, piled high with boxes in one corner, a few broken picture frames in another, and occasionally a forgotten treasure. In walking through it, in witnessing it, I’m beginning to have a sense both for its reality and for its unreality.

I’m finding intriguing new connections between what I’m experiencing and Christian teachings I’ve heard many times before. Author and spiritual teacher Cynthia Bourgeault, for example, links Centering Prayer (a Christian form of meditation) with the often-quoted line of Jesus, “He who would save his life must lose it.” Meditation is one way this can happen, she believes. “There comes a moment when the ego is no longer able to hold us together, and our identity is cast to the mercy of Being itself,” she writes. “This is the existential experience of ‘losing one’s life.’”

I’m beginning to see how this dying-to-self phenomenon can happen in a meditative practice, which requires letting go of our sense of self-importance and our relentless focus on the I. Instead, these techniques can create space for God to lead us to another way of being. Christian theologians have a fancy term for this process: kenosis, a Greek word meaning self-emptying. Jesus provided the model for how to do this: he was a master of the art of clinging to nothing and instead giving himself over entirely to God. He was reckless in his love for others, even at the cost of his own life.

Where did he get this ability to transcend the pettiness of ordinary existence? It’s clear from the Gospels that he sought solitude again and again in his life, retreating often to pray. He advised his followers to do the same, directing them to pray in secret behind closed doors. “Then your Father, who sees what is done in secret, will reward you,” he said.

And the more I think about it, his promise isn’t all that different from what the Buddha taught. The Buddha spoke of inner awakening; Jesus about salvation. Both encourage us to build a bridge between the small self and something greater, truer, deeper—-and both teachers say that the most important part of our practice happens not when we’re on our cushion or praying in secret, but after we open our eyes and re-enter the world in a new way.

Jesus called this place the Kingdom of Heaven, and it’s open to everyone, anytime. But sometimes an app helps.

Stay in touch! Like Holy Rover on Facebook: