Thoreau was 27 years old when he built his hut on the shore of Walden Pond, which is a small body of water less than two miles long on the outskirts of Concord. The building of it must have been an intoxicating experience for him, this man who had so often relied on charity but who now was independent at last (though it must be admitted that he was living rent-free on borrowed land). Thoreau spent his days writing in his journal and working on the manuscript of what would become A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers. He fished, played his flute, and tramped through the forest, keenly observing the changes of the seasons in the woods and waters around him.

His emotional life was troubled, for he was grieving his dead brother, his teaching career had floundered, and his prospects for a career as a writer looked bleak. He took solace not only in nature, but in the companionship of friends. He frequently walked into town to socialize and would entertain guests at his home as well. While the popular image of him is of a recluse and loner, he actually enjoyed the companionship of like-mind folks. “I had three chairs in my house; one for solitude, two for friendship, three for society,” he wrote in Walden. “When visitors came in larger and unexpected numbers there was but the third chair for them all, but they generally economized the room by standing up. It is surprising how many great men and women a small house will contain.”

After two years, he decided that his experiment in simple living had run its course and he moved back into Concord. “I left the woods for as good a reason as I went there,” he wrote. “Perhaps it seemed to me that I had several more lives to live, and could not spare any time for that one.”

But out of that two-year experience, something magical emerged.

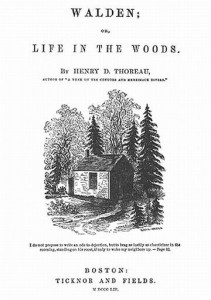

Walden is based on the journals Thoreau kept at Walden Pond, but he would spend seven years laboriously rewriting and revising them. In Walden Thoreau invents not only memoir writing but also nature writing. More importantly, its voice speaks to us like that of a prophet, calling us to a new way of living, one of simplicity and harmony with the natural world. The prose is both down-to-earth (detailing the amount he spent on each part of his house, for example) and lyrical in its descriptions of the joys and wonders of the landscape around him. Its pages exemplify the joys of a life lived simply, thoughtfully and deliberately.

Writes Susan Cheever in American Bloomsbury: “What creates a masterpiece? In the case of The Scarlett Letter and Walden, both arguably the finest works of two men whom we now regard as great writers, the impetus seems to have come from a sharp despair. Both men felt, as they began to write, that they had nothing more to lose. Hawthorne had lost his job, his mother, his hometown; Thoreau had lost his brother and the prospect of anyplace to live besides a homemade hut on borrowed land. There is a fearlessness about both these books, an honesty about the human heart, with its petty angers and dreadful fears, that neither writer found again.”

Thoreau became sick soon after the publication of Walden in 1855. He had tuberculosis, and his lungs were further weakened by working amid the fine dust and lead shavings of his family’s pencil factory. When someone asked him if he had made his peace with God, Thoreau replied, “I didn’t know we had ever quarreled.”

Concord, which for years had shaken its collective head at his peculiarities, realized that it loved him after all. At his death in 1862, the town’s children were let out of school to attend his funeral and the church bells tolled 44 times, one for each year of his life. Appropriately, his coffin was covered with wildflowers.

It would be many years before Thoreau’s genius would be recognized by the rest of the world. Thoreau earned nothing from the publication of Walden, and after his death he was remembered as a minor disciple of Emerson, if at all. But in his eulogy for his friend, Emerson got it exactly right: “No truer American existed than Thoreau. The country knows not yet, or in the least part, how great a son it has lost.”