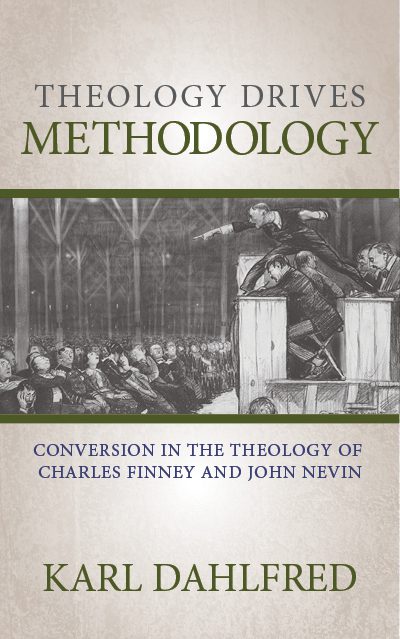

I recently had the privilege of reading Karl Dahlfred’s Theology Drives Methodology: Conversion in the Theology of Charles Finney and John Nevin. It is a published version of his Th.M thesis (Talbot School of Theology). It is well written and organized so that readers can clearly understand the the relevant history and theology being discussed.

Dahlfred is an OMF missionary living in Bangkok. In a few weeks, he’ll answer some of my questions about the book and how we might apply its insights.

Dahlfred is an OMF missionary living in Bangkok. In a few weeks, he’ll answer some of my questions about the book and how we might apply its insights.

Dahlfred uses Finney and Nevin to examine the larger issue of how one’s theology influences one’s evangelistic methods. His thesis might be summarized, “Methodology is not neutral. Churches may be undermining their very mission by using borrowed methodology that is hostile to their core convictions” (Kindle Loc, 3191).

The contrast between the two is made abundantly evident throughout the book. Finney typifies a pragmatic, Arminian-leaning, evangelism-focused strand of evangelicalism. Nevins represents a meticulously conservative, Calvinistic leaning, church-based expression of evangelicalism. Finney popularized such things as alter calls (invitations to repent at the end of church meetings), standing or raising hands as an acknowledgement of faith, and the “anxious seat.” Nevin worried that such methods led to false conversions since the pressure of the emotionally laden meetings could often manipulate people’s emotions, leading to false “decisions” to follow Christ.

Finney emphasized the decisive role of human free will and limited God’s sovereignty to the manipulating of circumstances. Nevin, on the other hand, thought God must first change a person’s heart (via regeneration) in order that he or she would believe (thus convert). As a result, Finney felt it was imperative to bring people to a point of crisis and demand an immediate decision. Methodology is to be determined more by the needs of the listeners rather than Scriptural precepts. He even sees methods like alter invitations and the anxious bench as modern equivalents to baptism. Dahlfred points out that Finney’s Systematic Theology gives virtually no attention to the doctrine of the church and to God’s attributes (Kindle Loc 2641, 3018).

Nevin regards the Church as God’s primary ordained means of spreading the gospel. Through faithful preaching, pastoral attentiveness and visitation, and godly conduct, God would help people to come under conviction of the gospel proclaimed by the church. Contrary to Finney’s charge, Nevin and those like him did not reject the use of means in evangelism. In other words, methods did matter to Nevins, however, one must be careful that methods do not undermine the diverse aims of Scripture and/or obscure the glory of God with man-centeredness. Dahlfred summarizes one of Nevin’s concerns by saying revivalism’s “promotion of individualism [makes] the Church redundant” (Kindle Loc 1036). In addition, Nevins rejects Finney’s pragmatic approach because “instead of destroying nominal Christianity, it actually created it” (Kindle Loc, 2879).

Dahlfred’s book is largely descriptive. He sides with Nevins after briefly assessing the two views from a Scriptural standpoint. The book has tremendous value for catalyzing thought about modern missiological practice. Though the book generally focuses on soteriology, I found some of the most provocative and helpful insights to concern ecclesiology. One’s soteriology will direct methodology, which then shapes the church that emerges. There are very few books that deal so directly with the relationship between theology and methodology. It’s a relationship many people talk about but few examine with the carefulness of this book. Dahlfred’s work serves as a good catalyst.

In the next post, I’ll attempt to relate Dahfred’s reflections to the current state of evangelicalism.