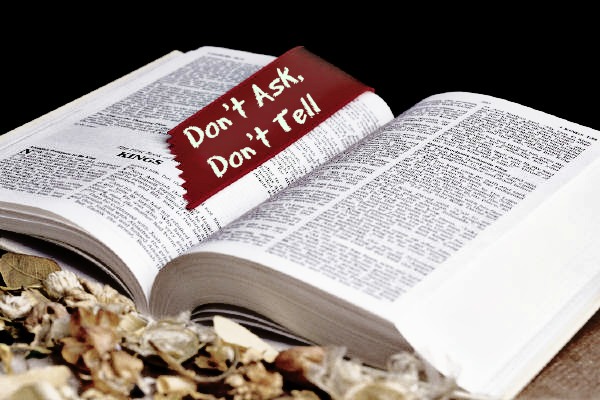

When people are not against something but not necessarily “for” it, what do they do? They adopt a “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy.

In theology and specifically contextualization, I think a similar dynamic can sometimes occur. Perhaps we will affirm some truth claim/doctrine, yet we virtually never talk about it. Functionally, we have a “don’t ask, don’t tell policy.” If they don’t ask, we don’t tell.

In theology and specifically contextualization, I think a similar dynamic can sometimes occur. Perhaps we will affirm some truth claim/doctrine, yet we virtually never talk about it. Functionally, we have a “don’t ask, don’t tell policy.” If they don’t ask, we don’t tell.

Why be hesitant to talk about themes that we believe in?

It is easily to believe that if we do affirm some facet of an issue, then we are not affirming some other aspect. We fear being misunderstood. Think through a lot of common controversies: If you here someone talk about how the gospel compels us to do “social justice” ministry (care for orphans, slave trafficking, education, poverty, environmental needs, health concerns, etc., then someone else will quickly jumpy in wondering if the first person is minimizing eternal life and salvation. Or, take the atonement. If an individual emphasizes the “Christus Victor” theory of the atonement, some may wonder if he or she cares much for penal substitution.

Let’s think about this in terms of missions and contextualization.

What if someone wanted to explore the doctrines of justification and Christ’s atonement, but rather than use traditional legal motifs, he explored the theme of honor-shame or “face”? How quickly would someone wonder if that person really believed in traditional law-oriented conclusions? I faced these kind of questions when I first began my research on honor-shame in connection with salvation.

The most common objection went some like this: “You just can throw away law-language.” Or they might say, “Sure, we need to talk about honor-shame, but we have to get to law if we are going to explain the gospel.” People assume that my particular focus at the same somehow implied a denial or minimization of their own preferred category–law.

Couldn’t I ask the same question in reverse? If you agree that themes like honor, shame, and glory are key biblical eyes, then why do you not mention much more? Are you denying or minimizing them? Is God’s face (i.e “glory”) not important? Are we to ignore the countless verses that talk about human shame? Doesn’t Paul, in Romans, parallel salvation with people not being put to shame (Rom 5:5, 9, 10; 10:11–33; cf 9:33)?

Likewise, we cannot necessarily conclude that criticism implies rejection. “Right” and “wrong” are not the only two categories by which to judge something. An idea or system can be incomplete. What is affirm may be right; however, its silence on some issue is deafening. In that case, one must critique where it is seriously deficient. Sometimes, the right distinction is not “right” versus “wrong.” Instead, we want to discern the major and minor themes and problems.

We must not compromise the gospel by settling for truth.

Imagine what this all means for contextualization.

If our theologies are only big enough to account for one or two themes, we do not appreciate the rich array of ways the Bible talks about countless issues. We then set up one text and theme against another biblical passage and idea.

When a Westerner, for example, crosses cultures, the consequence may then be that he or she talks only about the legal dimensions of the Bible and salvation, entirely neglecting what is arguably a larger category of thought––honor and shame. Whatever the comparable “size” of the two metaphors, honor-shame is not minor idea in the Bible.

Functionally, we can adopt a “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy. If they don’t ask about things like collective identity and “face”, then we won’t tell them. We might not overtly deny that these issues matter, but our silence can then be harmful. In fact, we must be on guard that we not “Judaize” people from other cultures as a result of our nearly exclusively highlighting one theme over another.

Of course, we can’t say everything all the time; however, we should say some things some of the time. Otherwise, what results is an unholy silence.