(For full disclosure, I recently become the new book reviews editor for Themelios’ Mission and Culture section.)

I should first add a note of appreciation. Without question, Song strives to protect the church against syncretism and wrong interpretations of the Bible. It’s refreshing to see his candid engagement with the book since many book reviews are dry reads.

Nevertheless, Song seriously misinterprets what Elshof does in Confucius for Christians. I’ll survey some of Song’s comments.

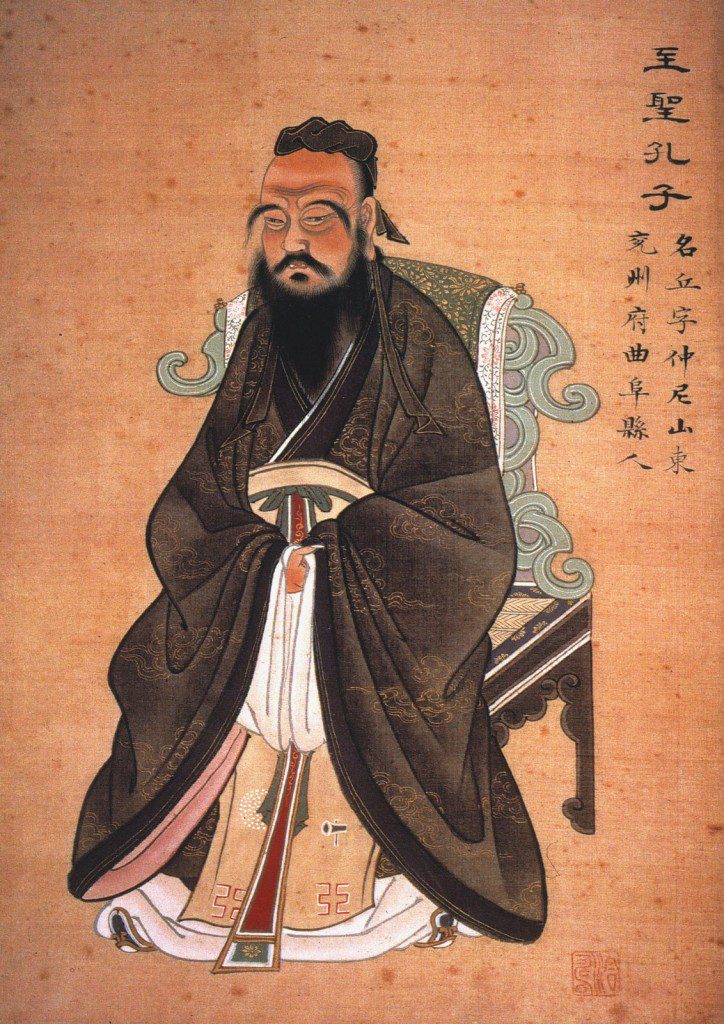

Confused about Confucius?

Song objects to Ten Elshof emphasis on Confucianism centrally as a type of moral or wisdom tradition. He says Ten Elshof’s “understanding of Confucianism as a wisdom tradition is confusing, problematic, and misleading,” citing sociologist Anna Sun, who “observes that it is common for a Confucian to worship Taoist Caishen (“god of wealth”) and Buddha together. Thus, it is syncretic for Ten Elshof to propose the identity of ‘Confucian Christian.’”

In my opinion, Song’s objection is unfair to what Ten Elshof actually says. Early on, Ten Elshof acknowledges,

But it’s a matter of some controversy among scholars whether or not Confucianism is, in fact, a religion. The question turns on complicated issues having to do with the defining marks of a religion.…. What is not controversial is that Confucianism (whether or not it is a religion) is a deep and influential wisdom tradition. (p. 5–6)

In other words, it makes no difference to Ten Elshof’s argument whether some Confucians worship this or that god. Ten Elshof never claims Confucianism is merely about ethics. Rather, he simply begins with what is common and not controversial about various expressions of Confucianism. Song’s appeal to his own experience in China or to certain person’s worship of gods does not set aside Ten Elshof’s specific point.

Recall that in recent years the Chinese government has utilized Confucianism for his own purposes. Certainly, the atheistic government isn’t exploiting Confucianism because they want to encourage the worship of gods. In fact, the Chinese Education ministry explicitly states that the use of Confucianism is “to aid ‘personality development,’ encourage altruism and instill ‘Chinese national moral thinking.’”

Is it syncretism to be a “Confucian Christian”?

Song thinks “it is syncretic for Ten Elshof to propose the identity of ‘Confucian Christian.’” Unfortunately, Song seems unaware of how intertwined are some cultural and religious/philosophical terms. In the West, unlike elsewhere, a person’s “religion/philosophy” is routinely separated from one’s identity in the larger culture.

For example, a number of evangelical Christians would claim to be “Muslim Christians” because they regard the term “Muslim” as a cultural marker, not necessarily implying the worship of the god of Mohammad. While people might not be comfortable with this, we can’t deny the fact that people use terms in multiple senses. Thus, the label “Christian” is diversely used to describe people, music, and even T-shirts.

Since Ten Elshof clearly states that he primarily uses “Confucian” to refer to a way of ethical thinking, it is unfair to charge him with syncretism, especially true since the phrase “Confucian Christian” prioritizes Christian identity whereby “Confucian,” for many people, becomes synonymous with “Eastern” or “Chinese.”

Are Analects and the Bible equal?

Song then accuses Ten Elshof of “valuing Confucian Analects and the Scripture as equal.” However, Song never substantiates the claim. It’s a sheer accusation. At the beginning of the book, Ten Elshof affirms, “As a Christian, my fundamental allegiance is to Jesus Christ” (p. 6). Furthermore, he adds that not everything that “Plato or Confucius taught can be reconciled with the claims of Christianity” (p. 3).

What then is Ten Elshof doing? In part, he uses Confucius to balance the influence of Plato on Western Christianity (pp. 3–4). In so doing, Confucianism is simply a tool to remind Christians that the Bible says a lot more about certain issues and priorities than people typically notice. For example, collective identity, the importance of family, mutual dependence, familial piety, practical ethics, etc.

It appears that Ten Elshof anticipates the sort of misreading we find in Song’s review. On page 2, Ten Elshof reminds readers that “to deviate from stereotypical Western Christian thinking is not to abandon Christianity.” Song seems to have not taken this warning seriously enough.

Restoring the Imago Dei?

Furthermore, I cannot make sense of Song’s criticism below:

It appears that Confucians later adopted Mencius’ (372–289 BC) view of the innate goodness of the individual. It seems that Ten Elshof has adopted an optimistic anthropology, and such a view affects his view of the family and filial piety. He explains that as for Confucians, “a human person just is a being in-relationship” (p. 12, emphasis original). Family becomes then “the primary venue for growth into the full expression of being human” (p. 13).

Unless I’m grossly missing something, this argument is a non-sequitur. On the one hand, it does not follow that the view of Mencius should somehow be attributed to Ten Elshof. On the other hand, nothing in what Ten Elshof says about being human should be construed as “optimistic anthropology,” at least in any unbiblical sense.

In context, Ten Elshof simply makes the claim that God created humans to live in community. Ten Elshof challenges Western individualism. He says,

To fail to be in relationship — and to do relationship well — is to fail at being human. To grow in goodness you must find your way increasingly into the full expression of what you are. And a human person just is a being-in-relationship. A life devoid of significant and well-ordered relationships can no more be human than can an organism devoid of a root system be a tree. (p. 12)

Therefore, he adds,

If we wish to be good, we must grow in our ability to be together. This is why filial piety is at the center of virtue — the root of goodness — for the Confucian. (p 13)

Ten Elshof issues a much needed corrective.

Far from denying human sin, he highlights the human problem that results from the fall. In fact, Song himself quotes Ten Elshof’s who says, “But after the fall, our obsession with knowledge has blinded us to the beauty of unknowing, impotence, submission, and dependence (p. 34).”

This hardly resembles an “optimistic anthropology” that warrants the concern expressed by Song.

Song seems to stumble on Ten Elshof’s phraseology. Song writes, “for Ten Elshof, it is possible to ‘find our way back’ by simply ‘reflecting on the Confucian emphasis on the love of learning’ (p. 35).” He apparently interprets Ten Elshof as referring to the imago Dei (image of God). Such an inference is unfounded. A simple search of the book shows that Confucius for Christians not once uses the terms “image,” imago, and Dei.

Read the paragraph from which Song quotes. Ten Elshof writes,

But at the center of the fall, then and now, is a profound disenchantment with the power-down condition built into the fabric of human nature. We’ve fallen out of love with what God designed us to be. Our obsession with knowledge has blinded us to the beauty of unknowing, impotence, submission, and dependence. Perhaps reflecting on the Confucian emphasis on the love of learning can help us find our way back. (pp. 34–35)

In context, “finding our way back” refers to our once again loving what God designed us to be––i.e. followers. Lest someone accuse Ten Elshof of being unclear, in the immediate prior paragraph, he explains,

Adam was designed for inclusion in a community wherein he would eternally be the follower. In the context of the community for which he was created, Adam was designed to be eternally — inescapably — in the power-down position. He was designed to be relatively impotent, submissive, dependent, unknowing — to be the follower. (p. 34)

The phrase “finding our way back” does not suggest that restore imago Dei through self-study, etc.

Rather, he simply seeks an answer to a question posed early in the book, “Steeped as we are in the patterns of thought and life shaped by an individualistic heritage, how can we find our way into something more human?” (pp. 10–11)

Was Jesus “merely a man”?

Finally, Song makes a charge against Ten Elshof yet again does not explain why. Song states, “Ten Elshof portrays Jesus as merely a man whose work was to make people follow his way to distinguish justice and love.” What is peculiar about Song’s criticism is that he pulls from Ten Elshof’s chapter on ethics. Naturally, he would focus on the ethical implications of Jesus’ life. It’s completely unfair to criticize Ten Elshof as if he tries to present a full-orbed Christology.

Instead, Ten Elshof simply tries to stress the fact that Jesus “invites his disciples to follow him into the nitty-gritty circumstances of life” (p. 58). Accordingly, Ten Elshof says Confucianism can help us reclaim important insights about Christian discipleship. He says,

But for those of us who’ve been caught up in the attempt to codify the ethics of Jesus, the Confucian emphases on context-sensitivity and the centrality of the master-apprentice relationship for the cultivation of the moral life may call attention in a new way to the emphasis on discipleship in Jesus’ strategy for bringing his students into his Way. (pp. 59–60)

In other words, Christian discipleship and ethical training is personal and practical.

Given Song’s criticism, I can only guess he wants Ten Elshof to somehow link Christ’s divine nature with ethics. Since none of us have a divine nature, I’m not exactly sure what that would even look like or how useful it would be.

If anything, what Ten Elshof does do only reinforces the findings of brilliant theologians like Richard Bauckham and others (which I’ve discussed previously on this blog). They point out a paradoxical truth of ancient Jewish monotheism. One thing that made Israel’s God so distinctive is that he dwelt among them in practical ways, intervening in concrete history. The Lord is not an abstract idea or a far off deity. Thus, Ted Elshof’s portrait of Jesus only reinforces the glorious truth that our God dwells among us “the nitty-gritty circumstances of life.”

In this post, I mainly defend Ten Elshof’s work by responding to Song’s review. In the next post, I’ll offer a more positive and constructive review of the book. I will highlight some of the great insights you’ll find in Confucius for Christians.