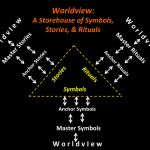

I’m thrilled to welcome Tom Steffen as a guest writer to the blog. I’ve asked him to introduce some of the big ideas you’ll find within his fantastic new book, Worldview-based Storying: The Integration of Symbol, Story, and Ritual. He is longtime leader in the orality movement. Teaching for years at Biola, he is the author of many articles and books, including Reconnecting God’s Story to Ministry and The Facilitator Era.

This first post is historical, looking back on the orality movement. The next post will discuss some practical tools for discovering another’s worldview.

“You’re not going to bed until I hear about what you’ve been doing in Palawan,” I impetuously dictated to Trevor McIlwain in the New Tribes Mission (now ETHNOS360) guest home in Manila in 1980. Our conversation went deep into the night. What I heard was something that would change Christian communicators and their recipients around the globe.

The next morning, I talked to our Field Director, Dell Schultz, about the possibility of getting McIlwain on the agenda for the upcoming South East Asian Leadership conference in Thailand two months out. The agenda was amended. McIlwain took four hours a day to go over his (still unnamed) model that tied evangelism and follow-up seamlessly together using Bible stories chronologically, beginning with Genesis. No one knew at that time that a spark had been lit that would turn into a modern-day movement—the Orality Movement.

Some Backstory

The McIlwains found themselves assigned to disciple a people movement among the Palowanos of the Philippines in which many were thought to have suddenly believed in Christ through the efforts of a missionary who communicated mostly through English. What the sincere but culturally naïve missionary did not know was that the Palawanos had a myth that told them if someone comes carrying a black book, do whatever he says.

That someone came. And they did what he said! Destroy your fetishes, get baptized, meet together… Contrary to expectations, the McIlwains soon discovered that most of the Palawanos had misunderstood the gospel. Destroying fetishes, abstaining from certain practices, and attending church services had become substitutes for salvation. Now what?

To try to rectify the problem, McIlwain decided to restart evangelism from the beginning of the Bible, identifying salvation themes from the stories presented in Genesis to the ascension. This provided a foundation for the New Testament Jesus story while allowing time for the Palawanos to sort out truth from error.

Chronological Bible Teaching (CBT)

He eventually called it Chronological Bible Teaching (CBT). It is now titled Firm Foundations. Syncretism birthed the CBT and the Orality Movement that would follow.

Over time, McIlwain developed a seven-stage story model that covered the entire Bible in a relatively short period, moving seamlessly from evangelism to follow-up:

- The 68 lessons of Phase 1 (Genesis 1-Acts 1) focused on evangelism (separation from a holy God and the solution through Christ).

- Phase 2 repeated Phase 1, adding the theme of security for believers.

- Phase 3 (Acts 2-28) introduced new believers to church life and the spontaneous spread of the Christian movement.

- Phase 4 (Romans-Revelation) covered the epistles, bringing conclusion to the God-story with Revelation.

Several assumptions drove CBT:

- The Bible is one story.

- It is not only the record of the words of God but also an account of the historical, revelatory acts of God.

- God, in his Word, has not only told us what to teach but by example, shown us how to teach.

- Doctrines can only be understood if taught according to their historical revelation and development.

- God prepared the Bible as his message for all cultures.

- There must be adequate Old Testament preparation for the gospel.

Morphings of the Movement

The first half of Worldview-based Storying: The Integration of Symbol, Story, and Ritual documents some of the major morphings that have transpired in the movements now almost 40-year history. Here are a few samples:

- The Bible started to be perceived as the Scripture Story rather than a textbook of systematic theology.

- Bible translation actually became “Bible” translation because it now included the Old Testament. Genesis replaced Mark as the first book to be translated.

- The Old Testament now played a major role in evangelism and follow-up. The whole is greater than the parts.

- New Tribes Mission passed the baton to the IMB (International Mission Board), who helped propel it into a global movement.

- Contrary to most movements, it began rurally and moved to the urban centers.

- Story was found to be as effective for urbanites as it is was for tribal people.

- Biblical theology and narrative theology challenged systematic theology as a start point.

- The definition of orality moved beyond story to include such things as drama, the arts, song, symbols, rituals, and so forth.

- It’s more than chronology. Start points can, and should, differ, but eventually circle back to Genesis.

- The curriculum moved beyond the dominant value system of guilt/innocence to include shame/honor, fear/power, and pollution/purity.

But a weakness remained. Few storytellers could tell you the worldview of their audience or how they tell stories.

Worldview-based Storying

How well do storytellers know the worldview of their audience? The second half of the book investigates the topic of worldview in relation to orality. That will be addressed in the next post. In the meantime, here’s the outline of the book:

Introduction

Part One: Tracking the Orality Movement

1 Pioneers of the Past

2 Rural Roots

3 City Connections

4 Movement Morphings

Part Two: Making the Case for Worldview-based Storying

5 Making the Case for Symbol

6 Making the Case for Story

7 Making the Case for Ritual

8 Making the Case for Worldview-based Storying

9 Envisioning the Future