The following is an excerpt from Reading Romans with Eastern Eyes: Honor and Shame in Paul’s Message and Mission. It is now available for pre-order at a discounted price!

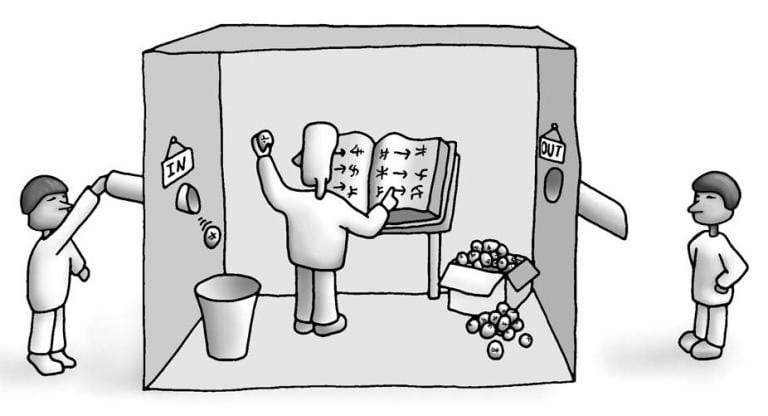

Many people are wary of “contextual” interpretations of the Bible. I completely understand the concern. More than a few “contextual theologies” co-opt Scripture for political or social purposes. Such readings seem more like applications than interpretations. This might be one reason people refer to “African theology,” “Indian theology,” or “Korean theology,” whereas “Western theology” is simply called “theology.”

Theologians increasingly recognize that all theology is contextual, since everyone reads the Bible from some cultural perspective. However, few people agree about the practical implications of this insight. Should contextual theologies use different interpretation methods? If context does affect biblical interpretation, how might we need to rethink our traditional methods of reading the Bible?[1] This book suggests a way forward.

Writing this book is risky.

On the one hand, many readers will be nervous about potentially mixing the Bible with culture. On the other hand, some people are uncomfortable speaking about an “Eastern” perspective. In today’s cultural milieu, such broad descriptions are sure to be criticized. Paradoxically, ethnicity and culture are household conversation topics that many people talk about with slight trepidation for fear of offending others.

But for the sake of the gospel and the nations, though, we need to take risks.

Who really has “Eastern” eyes?

Sports broadcaster Mike Tirico is known for being the first black broadcaster of a major PGA golf tournament. In an interview, however, he said, “I am not black,” because he has two white parents and grew up in an Italian neighborhood. He told the New York Times, “Why do I have to check any box? … If we live in a world where we’re not supposed to judge, why should anyone care about identifying?”

What does it mean to be “black”? Ironically, this is not a black-and-white question. Consider comments by Rodney Harrison, an NBC sports analyst and former NFL player. Harrison said about fellow former NFL player Colin Kaepernick, “He’s not black.” However, by conventional standards (that is, skin color), both men are considered “black.”

By contrast, megastar rapper Eminem has been dubbed a “white negro,” who “may have been born white but he was socialized as black, in the proverbial hood.”[2] Todd Boyd, a black man who holds an endowed chair for the study of race and popular culture at the University of Southern California, is more candid, saying that “Em is potentially more Black than many of the middle-class and wealthy Black people who live in mainstream White society today.”[3]

How do these examples relate to having an “Eastern” perspective?

Much in every way. Although Americans have long thought about what it means to be “black” or “white,” many still have difficulty defining who in particular is “black.” These examples illustrate a point: in some respect, being “black” is about more than skin color.

In the same way, people do not have an Eastern perspective simply because of nationality, skin color, or even ethnic ancestry. Although a counterintuitive idea, this chapter will demonstrate why readers from Alabama, Berlin, or Nairobi can use an Eastern lens to interpret the Bible.

Along the way we’ll answer a few key questions, like: What is an “Eastern” perspective? Do categories like “Eastern” and “Western” merely play on worn stereotypes? And how do Westerners adopt this perspective? We will first consider why anyone can read the Bible with Eastern eyes.

[1] I do not advocate a reader‐response method or “eisegesis,” whereby one inserts ideas foreign to the Bible into our interpretation. Instead, this book simply heeds the constructive insights from books such as E. Randolph Richards and Brandon J. O’Brien, Misreading Scripture with Western Eyes: Removing Cultural Blinders to Better Understand the Bible (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2012).

[2] Carl Hancock Rux, “Eminem: The New White Negro.” Pages 15‐38 in Everything But the Burden, ed. Greg Tate (Harlem: Broadway Books, 2003), 21.

[3] Todd Boyd, The New H. N. I. C.: The Death of Civil Rights and the Reign of Hip Hop (New York: NYU Press, 2002), 128.