Although it contains several misunderstandings, I am grateful for articles like “Did the Apostles Proclaim an Honor-Shame Gospel?,” recently posted on a missions website, AccessTruth. The writer expresses many of the same concerns I’ve heard elsewhere.

This series will answer common objections people have to honor and shame as they relate to the gospel and contextualization. Hopefully, my responses will clarify a few key ideas that remain muddled in people’s minds. In this first part of the series, I’ll comment on the biblical interpretation.

What “controls” biblical interpretation?

I appreciate the author’s clarity in stating what bothers him. He says,

“My concern, from a missiological standpoint, revolves around the controlling interpretive role that the honor-shame movement grants to the target audience culture.”

In a footnote, he adds,

“I highly value the target culture and its interpretive role in communicating the gospel. However, I do not see it as having the controlling interpretive role that the honor-shame movement wants to give it. The culture affects the presentation of the gospel, but it does not determine the content of the gospel.”

In response, I would agree if it were true that proponents of honor-shame movement wanted to grant the target audience a controlling interpretive role. However, I and others adamantly reject anything that smells like eisegesis or “reader response” interpretations of the Bible.

What should control biblical interpretation. Answer: The Bible.

What does that mean more specifically? We must read the biblical text in context. “Context is king.” The Bible’s own literary and cultural context should shape our interpretation, not our context or agendas.

Why the confusion?

So why the confusion? I and others have labored to point out an undeniable fact and limitation in the interpretive process. We all have perspectives that are limited by our own experience, assumptions, and (sub)cultures. It cannot be any other way. We are not omniscient. At best, we can gain only a partial glimpse at the ancient world as seen by the biblical writers. In myriad ways, ancient biblical cultures are more foreign to us than cultures that exist today.

This does not imply we are so hopelessly disconnected such that we can’t possibly interpret the Bible faithfully. Humility requires we simply acknowledge two points.

1. We all have limited perspectives.

2. Our cultural vantage point inevitably influences our interpretations, whether for better or worse.

By comparison, we all know the value of time and experience for understanding the Bible and the world. Ideally, a more mature perspective helps us better to grasp key ideas in the Bible. Just as we admit the limitations of our 25-year-old self, so we acknowledge the limits of our cultural perspective. Even with such limitations, we can discern much truth, but we all have room to grow.

What can we do?

While most people concede this point, one scarcely finds anyone talk about how to solve the problem. How do we improve biblical interpretation when inevitably read the Bible through historically and culturally biased lenses? Of course, we need to understand the ancient biblical context, but, as we’ve noted, we’re limited in our ability to fully apprehend the worldview of the original audience.

So, what can we do? I want us to get practical and not merely acknowledge the problem in theory.

Once we admit the influence of culture on our interpretation, I suggest we harness it for our advantage. How we do that is the subject of One Gospel for All Nations. In the final chapter, I explain why the approach I suggest is not eisegesis and does not allow contemporary cultures to have a “controlling interpretive role.”

“In order to interpret and apply Scripture, it is critical that we balance our particular perspective by becoming aware of other ways of seeing the world. Let me reiterate a quote that captures the spirit of this chapter quite well…. ‘[A] cross-cultural reading is more objective than a monocultural reading of the biblical text.’ Inevitably people from some cultures will grasp aspects of biblical teaching more easily than those from other cultures (and time periods) …” (p. 183)

We cannot entirely set aside our worldview lens, but we can certainly try to broaden our perspective. Notice I said “broaden,” not replace.

I reject any suggestion that we should prioritize any cultural lens (e.g., honor-shame, guilt-innocence, fear-power, etc.) when reading the biblical text. I and others merely advocate the need to broaden our cultural lens. Why?

“…the Bible was written for all humankind. Therefore, interpreting the Bible is not the exclusive privilege of any one particular culture or tradition” (p. 144).

Practical Implications?

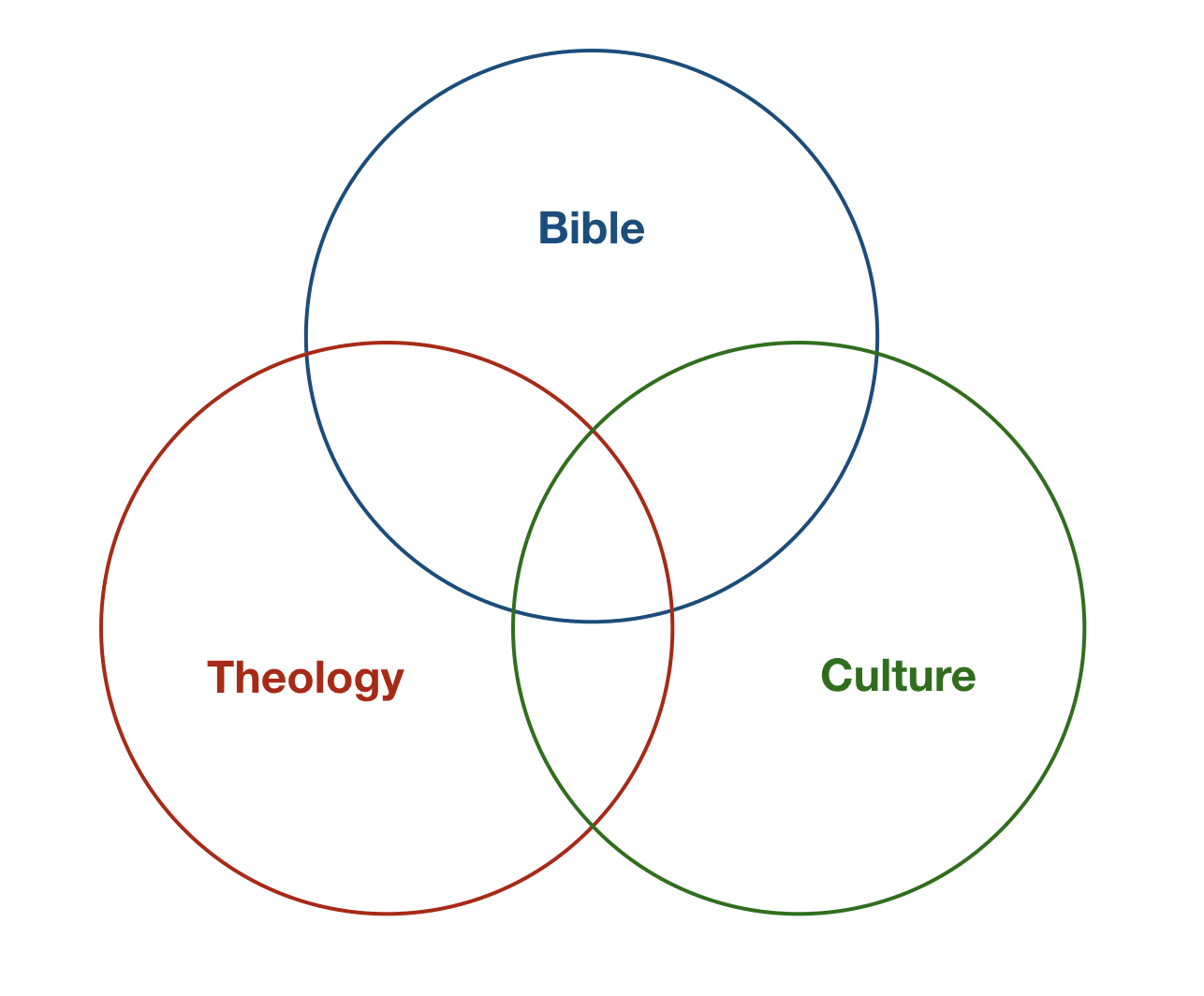

What happens if we admit our limitations but do nothing about it? We will eventually confuse the Bible with our own theology. In other words, we will limit or mistake the Bible’s message to the scope and content of our theology, which is partially filtered by our culture.

As a result, we might affirm many glorious biblical truths yet overlook or underemphasize various other biblical teachings. This does not honor God’s word.

As a result, we might affirm many glorious biblical truths yet overlook or underemphasize various other biblical teachings. This does not honor God’s word.

On the other hand, what happens if we take seriously the above ideas? What if we do broaden our cultural lens? What if we do engage in serious dialogue with people who read the text from different cultural backgrounds?

“Naturally, the various interpretations that result will have differing points of emphasis. Trying to reconcile these competing ideas only complicates the interpretive process. Interpreters will be tempted to accuse one another of eisegesis, whereby people force a meaning into the text that is actually foreign to the author’s intent. Likewise, readers will be quite unaware of their own eisegesis, since they naively presume the biblical author categorized the world in the same general ways that they do. One should not assume that these differing interpretations contradict; they may simply have distinct points of emphasis.” (pp. 183-84)

This last paragraph from One Gospel captures a fundamental dynamic at work in the article posted on AccessTruth.

Honor and shame should not control how we interpret the Bible. The same should be said about any single aspect of culture. However, honor and shame should influence our theology as we become aware of topics and themes that concerned the biblical authors. It is their concerns that should shape our reading of the text.

In the next post, I will focus on what some call the “honor and shame gospel.”