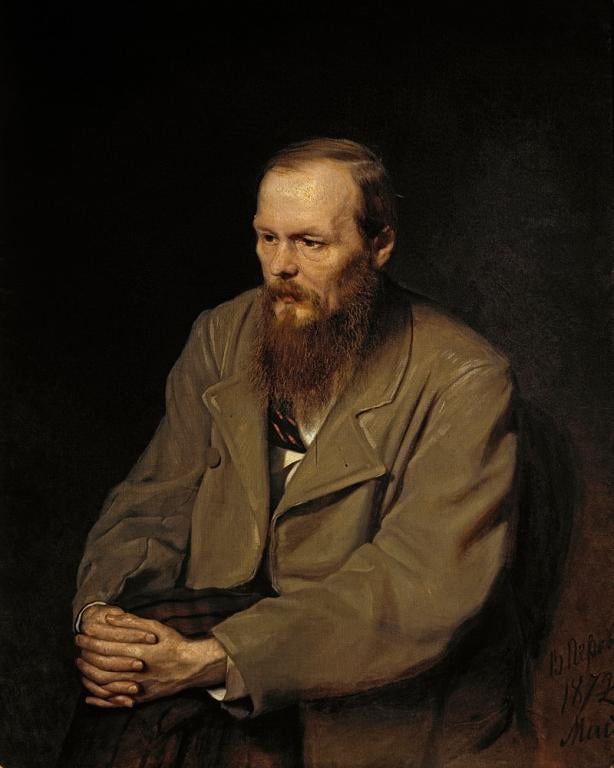

While rereading Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment recently, I’m stuck by its enduring relevance for us today. In the book, honor and shame are woven throughout the story, driving the characters’ moral and spiritual journeys. Set in 19th-century Russia, where honor was highly valued and shame carried public weight, Dostoevsky uses these themes to challenge utilitarian morality, depict the destructive nature of guilt, and show how humility and faith can lead to redemption.

Shame and Raskolnikov’s Inner Struggle

Raskolnikov, the protagonist, is consumed by both personal and social shame from the start. His poverty and failure to meet social expectations make him feel worthless. They drive him to adopt a nihilistic worldview where he seeks to prove he’s an “extraordinary man” above common morality (comparable to Napolean). His murder of the pawnbroker is not just a crime but an attempt to assert his superiority.

However, this act thrusts him into deep psychological torment. Though his shame isn’t publicly exposed at first, it festers internally. It leads to paranoia, physical illness, and erratic behavior. Dostoevsky shows that shame, deeply bound to our conscience, cannot be reasoned away, no matter how philosophically justified a person may try to make their actions.

The Social Dynamics of Honor and Shame

Dostoevsky contrasts Raskolnikov’s personal shame with society’s notions of honor.

Characters like Luzhin and Svidrigailov pursue honor through wealth, status, or control over others, exposing how superficial and corrupt social definitions of honor can be. Luzhin’s manipulative courtship of Raskolnikov’s sister, Dunya, and Svidrigailov’s hedonism are foils to Raskolnikov’s struggles. They show how detaching honor from true virtue leads to moral emptiness. At the same time, the fear of public disgrace intensifies Raskolnikov’s inner conflict, particularly in his interactions with the sharp and probing detective, Porfiry.

Characters like Luzhin and Svidrigailov pursue honor through wealth, status, or control over others, exposing how superficial and corrupt social definitions of honor can be. Luzhin’s manipulative courtship of Raskolnikov’s sister, Dunya, and Svidrigailov’s hedonism are foils to Raskolnikov’s struggles. They show how detaching honor from true virtue leads to moral emptiness. At the same time, the fear of public disgrace intensifies Raskolnikov’s inner conflict, particularly in his interactions with the sharp and probing detective, Porfiry.

These moments illustrate the communal nature of morality in Dostoevsky’s view: individual actions ripple through the social order, and public shame can bring to light truths that private guilt keeps hidden.

Sonia: A Redemptive Vision of Honor

Sonia, who has suffered profound shame through her descent into prostitution, embodies a redemptive and spiritual kind of honor. She doesn’t internalize her shame but embraces her suffering with faith and humility, finding dignity in loving her family and trusting God. Sonia’s example challenges Raskolnikov’s approach to shame and guilt, pointing him toward confession and repentance. A prostitute is the virtuous truthteller. Through her, Dostoevsky redefines honor as alignment with a higher moral and spiritual truth rather than social validation.

Redemption Through Confession and Suffering

The turning point comes with Raskolnikov’s confession, spurred by Sonia’s encouragement. In admitting his crime, he faces the public shame he’s feared, yet this act marks the beginning of his spiritual renewal.

In Dostoevsky’s framework, honor isn’t about avoiding shame but confronting it and allowing it to lead to transformation. While in Siberia, Raskolnikov experiences a spiritual awakening, mirroring Sonia’s embrace of suffering and finding purification through humble repentance. Surrendering to love begins the subversion of shame.

Conclusion

Through Crime and Punishment, Dostoevsky examines the transformative power of honor and shame in shaping human morality and identity. Shame exposes the flaws in Raskolnikov’s utilitarian philosophy, while the true nature of honor emerges through faith, love, and moral integrity.

Dostoevsky critiques social values that prioritize wealth and status, offering a vision of honor rooted in humility and alignment with God’s truth. His work challenges readers to reevaluate their own understanding of honor and the redemptive role shame can play in the human experience.

For those interested, I also have similar posts focusing on honor and shame within Othello and Frankenstein.