My aunt is attracted black men. That means I now have two black cousins related by blood. During middle school, my dad, one of my cousins and I went to the store. I kept my distance from them, at least 20 yards.

It was not until adulthood that I found out my actions were grossly misunderstood. Apparently, my father supposed I was embarrassed to have a black cousin. I was appalled at the suggestion. I love my cousin deeply. We were close. In actual fact, I was embarrassed to be around my dad! (I won’t go into my reasons at the time.)

This story illustrates how prone we are to misinterpret and mislabel people’s actions. Everyone has personal baggage. Our background shades our perspective. We create narratives that filter our experience and can unfairly condemn even those near us.

What is “white privilege”?

At A Life Overseas, an Asian writer Grace Lee complains of “white privilege” in western missions. She doesn’t define the term. Instead, she gives examples of past offenses.

As a missionary, she frequently feels “ignored and irrelevant within the predominantly white missions community.” She recounts a time

our missions agency was considering mobilization of internationals. Leaders from around the region gathered together to discuss the pros and cons of such an endeavor. I and other minority members expressed our apprehension of recruiting locals into a primarily white organization, citing concerns about expansionism and assimilation.

She concludes, “instead of hearing [her] reservations,” the task force moved ahead with plan to mobilize internationals in an integrated fashion.

She then adds,

I think of my father, who has written countless books about missions, is a sought-after speaker for conferences, and has five decades of ministry experience as a missionary, pastor, professor, and mobilizer. Go anywhere in the world and ask any believer with my ethnic background, and they probably know of him. Yet very few white missionaries have ever heard of his name.

Her experiences teach her that non-whites are “invisible”, “ignored” and “unheard.” Thus,

When those with white privilege are the only people with influence, people of color inevitability feel stripped of power. When theirs are the only voices we hear, people of color feel unheard. When there is a lack of representation and diversity within the missions community, people of color feel dismissed.

I’m deeply saddened by her pain. Various things in her past have obviously left her feeling wounded. As I reflect on her comments, a few thoughts come to mind.

A lingering question is this: What is “white privilege”? Although the answer seems obvious, I’ll explain why the question deserves attention.

On the one hand, “white privilege” could be a mere description. As such, the term describes a historical and social phenomenon whereby white people have gained certain privileges as a result of various unfortunate events in the past.

On the other hand, it might carry negative connotations about those with white privilege. Specifically, the term could suggest that such people continue to have prejudice and so actively protect certain privileges for white people to the exclusion of non-whites.

Both circumstances are lamentable. But the second claim is far more incendiary and represents a grievous obstacle to the church’s unity and mission. How we understand “white privilege” makes a significant difference not only in how we understand her complaints but how we move forward as Christ’s followers.

In my opinion, her strong words suggest the second, more provocative meaning. They imply a systemic albeit subtle effort (in her words) to “dismiss”, “ignore” “silence” and “disenfranchise” people of color.

If so, her blog post is riddled with problems. Furthermore, it represents a destructive approach to a multifaceted problem that is easier to name than solve.

Where is “white privilege”?

Lee asks for “compassion”, which she explains as “suffering with” those like herself. As our sister, we desire to empathize with her. Yet, Jesus-like compassion has an active, problem-solving nature (cf. Matt 14:14; 15:32; Luke 10:33).[1]

What is the basic problem underlying Lee’s essay? It lacks generosity.

By this, I mean she seems to assume the worst––or something thoroughly negative––about believers, especially missionaries. While no one is perfect, we have many reasons to assume the contrary–– that most white missionaries are not prejudiced against non-white missionaries. She assumes ill of others without considering other possible reasons for her complaints.

I’ll begin with the items that least support her contention.

1. The organization did not listen to her advice

This is a flawed example for multiple reasons. First, considering someone’s advice and agreeing with their advice are entirely different. Second, a task force receives a lot of (contrary) input from many people. It’s possible that other non-Caucasians (whether from inside or outside the organization) agreed with their decision. There is no reason to insinuate prejudice. Third, they might simply disagree with Lee’s view. Being non-white does not entail always being right.

Someone could just as well argue that creating organization silos based on ethnicity or skin color perpetuates our basic problem. A more integrative method, even if it’s messy, might work better in the long run.

2. Few white missionaries know her father’s name

Her objection sounds more like a statement of love for her father than a legitimate reason for claiming “white privilege” (as subtle prejudice). It seems she wants people to know her father but many do not. So, she feels hurt on his behalf. Her affection for her father is admirable. That doesn’t make it good evidence for her argument.

For one thing, we must accept her word that he is as famous as she claims. Also, she presumes to know what white people know or don’t know about him. That’s a big claim. What’s more, we know nothing about the nature of his ministry, who he published with, how many books are published in what languages and about what topics, where he traveled, where he’s taught, etc.

Moreover, she seems unaware of a more basic consideration. Even white people are relatively clueless about many very famous white theologians and missiologists.

For example, I know many missionaries that have never heard of N. T. Wright, despite the fact he probably is the most well-known or influential theologian alive. Not only that, I’ve found that theologians don’t know famous missiologists and missiologists are unfamiliar with well-known theologians. It’s not a color thing.

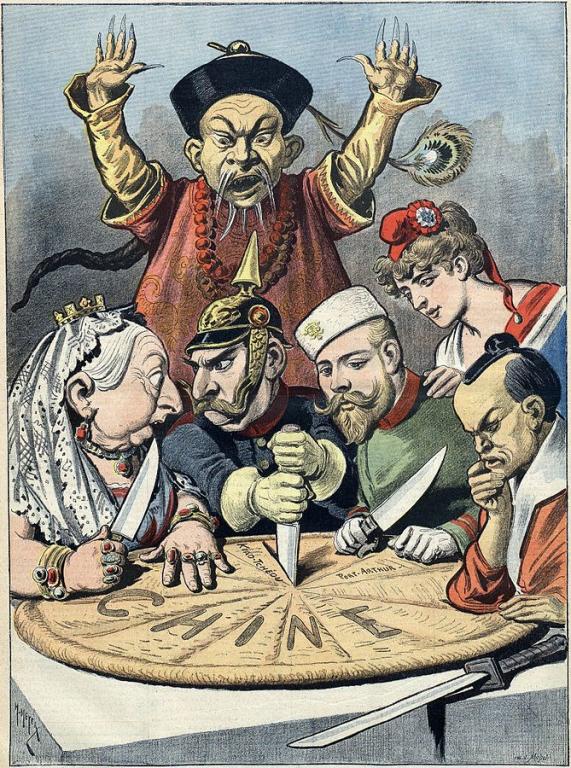

3. The disproportionate number of white missionaries

This point seems to be Lee’s root concern. Obviously, there are many historical reasons for this. Contemporary missionaries cannot be blamed. Systemic change takes time.

She does not entertain possible influences that might explain why progress is not more rapid. For instance, many Asia families ––including Christian families––fiercely resist their children becoming missionaries because it lacks the prestige or does not provide a high income.

It’s also possible that many churches insufficiently emphasize missions. I have listened for hours to people from New York’s Chinatown as they rant with anger about Mainland China. Many of them still hold grudges and prejudice against China. One should not ignore factors like this, not to mention other possible aversions people might have to cross cultural work.

One person responded to her post, “I have been struck by how very non-diverse American missionaries seem to be.” The question remains––who is to blame? I don’t think it’s missionaries, the people who serve people who typically have a different ethnic background. By analogy, most NBA players are not Caucasians. Are we to assume the reason is that non-white players are discriminating against whites?

“Everyone is overlooked sometimes.”

We need to engage in debates about discrimination and prejudice in more productive and generous ways. A Life Overseas posted Lee’s article on Facebook. One women, Lisa, wrote

The use of the term “white privilege” was a poor choice. White privilege discussions are about shaming white people. We should not be doing that in the body of Christ. I’m a white missionary who has been on the field for more than thirteen years. My husband is Asian and an ethnic minority. I have not seen him ignored by my white colleagues. They are usually interested in his perspective. However, I have seen him railroaded by Asian colleagues, some of whom are Chinese.

Lisa then points out, “Everyone is overlooked sometimes.” J. K. Rowling’s Harry Potter was rejected 12 times before begin accepted. William Golding’s Lord of the Flies was rejected 20 times. Should we blame those rejections on the fact that Rowling is a woman or that Golding is a British white male?

I could likewise share stories of “Asian privilege” where people assumed––based on skin color–– that new American-born Chinese missionaries (who could not speak Mandarin) understood Mainland China better than long-term white missionaries.

Lee unleashes her personal hurt in a way that ultimately undermines the goal she seeks. She offers a compelling personal narrative that ultimate distracts from more concrete forms of discrimination. A very common example exists among Chinese pastors (not white missionaries). Potential church leaders are routinely passed over for no other reason than because they originally came from “out of town” (外来的人).

Finally, we not only need to change our terms and our tone; we should rethink our tactics. By framing her argument in terms of “white privilege”, Lee accomplishes two things, neither of which is healthy.

1. Lee shields herself from criticism.

This is because anyone who disagrees with her would have to talk past the emotive appeal of her argument. Objections from white people can be written off immediately as further validation of “white privilege.”

2. It’s so difficult to prove people’s motives.

As a result, her accusations are almost unassailable. As long as her rationale is somewhat plausible, one is hard pressed to provide counter evidence that completely dislodges the narrative she offers.

I am thankful for Grace Lee’s willingness to share her concerns. I hope a fruit of her article will be that we begin self-reflecting. Where might we engage in attitudes and practices that do not foster genuine unity?

As we do this, I urge people to give pause and also consider how they discuss these sensitive subjects. We should offer careful, clear and constructive arguments that advance the conversation. Are we accusing or asking genuine questions? Are there more generous ways to interpret others’ actions? What is a personal problem and what is a broader issue of prejudice?

And by His grace, we will honor one another in the process.

[1] Also, Matt 9:36; Mark 6:34; 8:2; 9:22; Luke 7:13; 15:20.