“In the ideology of the free market, freedom is conceived as the absence of interference from others.” William Cavanaugh [1]

The article question is easy to ask, but difficult to answer.

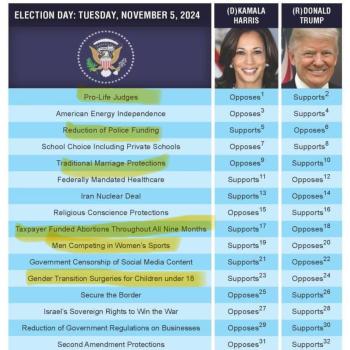

Have Politics Poisoned The Evangelical Church?

There are a couple factors affecting this article.

First, I look like an Evangelical on paper, but I have become fairly devoted to Ecumenism in recent years. One of the striking differences is engagement, i.e. in the marketplace and arenas like social justice, etc. These are political concerns some confessional communities have no problem working with.

Second, the above question is broad in scope, so I will niche it down.

My sub-question is about capitalism and worldview

Are some aspects of the capitalist system indispensable as our best way of today seeking to realize God’s intention for how we should live together? Are some aspects of the capitalist system unambiguously antithetical to this vision? [2]

To niche down further, I explore political capitalism, with an eye toward the free market economy (marketing, advertising, etc.).

Some authors will seem Evangelical. Others will not. However, all of them are dignified scholars, i.e. Theologians, ethicists, philosophers. I offer their views with little commentary of my own, as a literature review.

Although I do not always quote verbatim, I use extensive footnotes so you all can fact check my foray in political frivolity.

It is an enjoyable writing engagement.

Currently listening to the playlist: try jogging to this

I hope you all enjoy this longread.

For more reads like this, visit my category: Ethics & Society

One final caveat, I suggest this is neither an Evangelical nor an Ecumenical issue: politics poisoning the Evangelical Church.

First, nowhere in our founding documents is the separation of church and state required the way we understand it today. The principle has more to do with interference.

Second, in my opinion the authors reflect the paradigm shift from historical-criticism to post-critical postmodernity. This paradigm shift is more evident at the crux of Christianity and politics in America today than Evangelicalism or Ecumenicism.

However, I will allow you to draw your own conclusions from these snapshots of these authors, and there are other scholars, but I do not have time to write another e-book.

i. Theodore Levitt is first in the lineup.

He paints with broad strokes. Levitt actually compares good advertising to another field, the arts . . . good artwork or poetry. He says that everyone knows art and poetry serve a higher purpose, but they both embellish and distort freely to capture the imagination. Levitt quotes Charles Revson of Revlon cosmetics:

“In the factory we make cosmetics; in the store we sell hope.”[3]

With stories like this, Levitt seems a little more like a postmodern philosopher than an economist. He believes all communication is never the real thing we are talking about, so it is symbolic.[4] We always want the symbolic, the ideal.

“None is satisfied with nature in the raw . . . None is satisfied to tell it exactly ‘like it is’ . . . Few, if any of us accept the natural state in which God created us . . . Everybody everywhere wants to modify, transform, embellish, enrich, and reconstruct the world around him.”[5]

Levitt sees good in the fact man improves his surroundings with imagination.[6]

In effect, he may be chasing the theme of beauty, but he is applying it to advertising in ways that are surprising.

To Levitt the question is about the church’s stance intermingling with politics, specifically capitalism, with marketing as the example. However, Levitt narrows the question further. The question remains, how do we pursue beauty and symbol?

Levitt would say the end justifies the means. Worth is only measured by the audience our products serve.[7]

He states consumers are not interested in, “the moralizing logic of detached critics who pine for another age.”[8] He says, like it or not, marketers are caught in between what consumers want and regulations in the market. He seems like a postmodern realist, and I could be wrong.

ii. John Waide is next, with a moral argument against associative advertising.

John Waide is next, with a moral argument against associative advertising. These ads sell a product, but also appeal to a non-market good – i.e. friends, power, sex appeal, etc. So they are selling a connection between an item and usually some aspect of the good life.[9]

Unlike Levitt, Waide does not give advertisers a free pass. Advertisers look for a target audience, but he says they do not care for well-being, much less moral virtue. Instead he believes advertisers are teaching, you are what you own.[10]

John Waide takes issue with Theodore Levitt who argues in favor of advertising as a fun art we embellish like other arts.

Waide says:

“People have always had ideals, fantasies, heroes, and dreams. We have always told stories that captured our aspirations and fears. The very suggestion that we require advertising to bring a magical aura to our shabby, humdrum lives is not only insulting but false.”[11]

First of all, I do not see Theodore Levitt saying that advertising is the silver bullet, that it is something “we require.”

Secondly, I do not see Levitt pushing aside any of the arts that John Waide mentions. Levitt is merely suggesting that there are some principles of poetry and art that are utilized in good advertising as well.

In this way, I believe John Waide misrepresents Theodore Levitt. Waide’s balance of morality and virtue in advertising seems important. Waide offers some concluding suggestions, however he publishes in 1989, so I am not sure how he would write today.

iii. Rodney Clapp offers a wide history of the development of consumerism.

Basically, technology allows us to increase supply (more goods), so now we have to increase demand – and that is advertising.[12]

Rodney Clapp cites The Thompson Red Book on Advertising from 1901:

“Advertising aims to teach people that they have wants, which they did not recognize before, and where such wants can be best supplied.”[13]

Consumers are taught to be that way, not born that way. Now it has come much farther, as marketers have idealized and taught, “insatiability – the deification of dissatisfaction.”[14]

Basic cultural and Christian values are at stake, when one considers the values of consumer capitalism. Clapp argues for morality, or ethos, in advertising.

Rae and Wong review the chapter and declare, “Advertising can be described as a distorted mirror, at best.”[15]

iv. William Cavanaugh is pro-ethical in principle, with a much broader scope than advertising.

Cavanaugh sees ethical practices that affect others well as “communion” with them (i.e. he likes “Fair Trade”). He is also working between tensions, binaries such as negative freedom and positive freedom.[16] He states that now:

“In the ideology of the free market, freedom is conceived as the absence of interference from others.”[17]

I think this is important. If I am on the right track, Cavanaugh is not condemning the free market, but is stating it lacks a telos, an ultimate end or destination, which guides our virtues now.[18]

Cavanaugh draws from Augustine, who teaches freedom is not just freedom from something, but also a freedom moving to or towards something – a new take on the Classical Greek ideal of telos.[19]

Augustine asks a question that may prophetically speak to our postmodern consumerism, and to the overarching political question of this article in general:

“How, if they are slaves of sin, can they boast of freedom of choice?” Augustine [20]

William Cavanaugh states that marketing is an issue in consumer mentality. He also talks in depth about security surveillance of consumer activities (actually somewhat scary). Buyers are literally buying access to our buying habits and factoring it into marketing.[21]

Perhaps this is legal, but how ethical is it for someone to know my buying habits?

Cavanaugh addresses attachment and detachment, a relentless pursuit of something new.[22]

We are detached from producers who are detached from their workers who are manufacturing overseas.

Detachment allows us to value our comforts over theirs.[23]

Discontent, the desire for more, shopping instead of buying – are all at the heart of detachment.[24]

Consumerism is like a counterfeit search for transcendence, because we are always seeking something more.[25]

To balance detachment, Cavanaugh discusses particularization. We are now elevating and celebrating and heralding multiculturalism. Multi-national corporations offer a vast variety of products.[26]

Particularization has produced a world in which everybody is different, so nobody is.

William Cavanaugh makes note of the reality of: “‘mass individualism’: the more we celebrate our differences for their own sake, the more similar we become.”[27]

Cavanaugh connects the dots between politico-capitalism, consumerism, and religion. In the same ways that we can access all the products of the world and our local region, we can access all the religions. Like particularization and mass individualism, pluralism has elevated every religion, yet it does not recognize any particular religion.[28] He bemoans the loss of a guiding telos in global capitalism and pluralism:

“The pluralist is above and detached from all particular traditions . . . the consumer consumes; rather than being drawn ecstatically into a larger drama.”[29]

v. John R. Schneider offers positive arguments for capitalism.

Schneider reminds us Pope Leo XIII declares the virtues in owning property, the dignity and freedom of the individual, and character in freedom.[30]

Capitalism helped “The Greatest Generation” to forge a new America after the Depression, World War II, and through the Cold War.[31]

He offers statistics on how the percentage of the affluent in America has increased, and how those at the poverty line or below are still far better off than other nations.

John cites Augustine, Luther, Calvin, and Wesley.

He believes they focus on wealth that is not properly distributed. To their credit, he reminds us a capitalistic system never existed before America.

It is not until Jonathan Edwards and the Puritans that Christian views emerge helping us understand ourselves. Puritans are often misrepresented as originators of the Prosperity Gospel.[32]

I assume John Schneider refers to values like the Puritan Work Ethic, seemingly at the crux of the newly forged political freedom offered by capitalism in America.

What has capitalism afforded in regards to the poor of the world?

We do not utilize capitalism to take away wealth, but to create wealth, and we have impacted the world.

Schneider does not preach the virtue of simplicity.

He does not ignore the political woes of the system either.

We have set up politico-capitalism not to reward the bad guys, but people who prove their reputation.

John Schneider states there is nothing wrong when Christian virtue goes to a meetup with dignified work, and then reaps a reward.[33]

footnotes:

[1] William T. Cavanaugh, Being Consumed: Economics and Christian Desire (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans, 2008), 2.

[2] adapted from a presentation by Jared Ingle for Kevin Kinghorn and Jason Vickers, “TH634 Theology and Ethics of Work” (Asbury Theological Seminary, 2017).

Theodore Levitt

[3] Theodore Levitt, “The Morality (?) of Advertising,” in Beyond Integrity: A Judeo-Christian Approach to Business Ethics, 2nd ed., ed. Scott B. Rae and Kenman L. Wong (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2004), 341.

[4 – 8] Ibid., 342, 343-344, 346-347.

John Waide

[9] John Waide, “The making of Self and World in Advertising,” in Beyond Integrity: A Judeo-Christian Approach to Business Ethics, 2nd ed., ed. Scott B. Rae and Kenman L. Wong (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2004), 348-349.

[10 – 11] Ibid., 350, 352.

Rodney Clapp

[12] Rodney Clapp, “Making Consumers,” in Beyond Integrity: A Judeo-Christian Approach to Business Ethics, 2nd ed., ed. Scott B. Rae and Kenman L. Wong (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2004), 355.

[14] Ibid., 358.

[15] Scott B. Rae and Kenman L. Wong, “Marketing and Advertising: Commentary,” Beyond Integrity: A Judeo-Christian Approach to Business Ethics, 2nd ed., ed. Scott B. Rae and Kenman L. Wong (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2004), 364.

William Cavanaugh

[16] William T. Cavanaugh, Being Consumed: Economics and Christian Desire (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans, 2008), ix-x.

[17 – 26] Ibid., 2, 5, 7-8, 19, 35, 39-49, 65-66.

[27] Christopher Clausen, Faded Mosaic: The Emergence of Post-Cultural America (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2000), 7, quoted in Cavanaugh, 68.

[28 – 29] Cavanaugh, 70-74

John Schneider

[30] John R. Schneider, “The ‘New’ Culture of Capitalism,” The Good of Affluence: Seeking God in a Culture of Wealth, (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans, 2002), 15.

[31 – 33] Ibid., 18, 26-28, 37.