Yesterday subbing in high school English (I know!), we were discussing “flat” versus “rounded” characters. The kids noted that one of the conveniences of slapping together a stereotype or two, giving it a name, and making it a bit player in your story is that it is easier to kill that character. Neither the author nor the readers feel much loss in the passing of a character they never loved to begin with.

It’s a germane topic for high school students, who often go through life playing the “flat character” to their classmates. Your peers give you a label based on a superficial attribute, assume there’s nothing more to be known about you, done. Having your depth and complexity as a human being summarily dismissed is social death.

Adults do this all the time, and we do it especially when we want someone to literally die. Not “literally die” like what happens when you are seventeen and it’s already April and you still can’t get a date to the prom, but literally-literally die like what happens in war and genocide.

We flatten people into negative stereotypes — or in worst cases argue they don’t exist at all, or have no remaining rights at all — when we wish to excuse our plans to destroy them, whether partially or completely.

After 9/11, there was an abrupt about-face in public opinion concerning torture. Previously, Americans (and western democracies generally) had viewed ourselves as people who don’t torture. If you are too young to remember last century, I assure you: Prior to 9/11/2001, not torturing people was a value firmly embedded in our cultural norms across the political and religious spectrum. In the wake of the fear and anger following that momentous terrorist attack, very quickly we as a nation abandoned that identity; those of us who persist in rejecting torture as a moral option have largely been marginalized.

It’s not even really discussed anymore. The debate was held, “enhanced interrogation” won the day, Americans are now people who try not to think too much about the barbarism that has become an accepted military tactic.

If you are unable to remember the days before torture became acceptable to the American public, let me explain why we felt that way, back then. We felt that way because we acknowledged that even our worst enemies, even the ones who were literally Hitler and his minions, were still human. To kill in self-defense might be unavoidable, but even the enemy’s humanity needed to be respected once the immediate danger of battle had ended.

(This is the same reason police brutality is always wrong, even though there are occasions when it is necessary to use force to stop a genuine threat. Brutality is when you begin or continue to inflict pain or injury despite a lack of threat.)

Flattening people, the intentional refusal to experience an emotional connection, is how we justify all kinds of sins. Racism requires denying the complexity and full humanity of people we’ve categorized as not-like-us. Indeed the whole “Oh, I don’t mean you, I mean those other people of your group” is the homage racism plays to the experience of accidentally being able to relate humanely to someone you would otherwise have blissfully marginalized.

Flattening takes its toll even when you’re one of the lucky few in the out-group who gets the pass to be considered more or less fully human. Emily DeArdo writes about what it feels like to be one of the survivors of that mentality.

Flattening, of course, is a political tool, and lately it has become the political tool. Instead of appealing to the voter’s common humanity with the candidate or the cause, there’s an appeal to the lack of common of humanity with one’s opponent or opposition. As a result, we end up with this absurdly awkward interview between The Atlantic‘s Emma Green and Kyle Mann at The Babylon Bee. It’s the one job of a journalist to understand the subject of the story, but Green is categorically unable to understand the point of view of the person she’s interviewing. Meanwhile, over at the Bee, the humor has largely grown dull: You just can’t satirize effectively a subject you don’t know well.

It’s a case study in mutual-flattening. Liberals can’t understand conservative humor; conservatives are churning out weakened, one-note jokes because they lack a nuanced appreciation of the depth and breadth of liberal points of view.

This particular interview struck me as an especially vivid example of the intellectual self-destruction that occurs when we flatten because both publications are capable of excellently nuanced examination of a topic when they so choose.

***

When I began teaching debate, I rejected from the outset the widespread practice of having students defend positions they don’t believe. The goal of that practice is laudable: You want students to learn to see the opponent’s point of view. You want to un-flatten the debate. In practice, though, what you end up with are students skilled at intellectual dishonestly. This is of course in part the fault of thinking that there are only two sides to an issue, or that you can know before examining the issue what those two sides are.

Photo of a rainbow arching over a bright-red ship, blue sky in the background: “The Australian Antarctic Division’s icebreaker, the Aurora Australis, berthed in Hobart, Tasmania, Australia, under a rainbow. The French Antarctic vessel, L’Astrolabe, can be seen behind some yachts to the right of the Aurora Australis.” Click through to Wikimedia for more info. CC 3.0. Photo chosen semi-randomly, but conveniently metaphorical all the same.

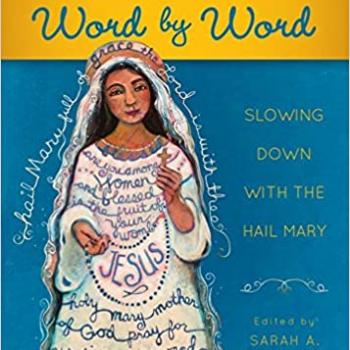

Related: If you’re Catholic and you’re ready to welcome into the Church people who don’t fit profile, there’s a book for that.