This will be dangerous work, these words. It be messy, and I will probably do it wrong. But it is important work. In fact, it might prove to be most important work, because it might be the key we are missing to our very own healing — as a nation, as a people, as a global community. It’s so important that I am willing to do it wrong, to put this out there and stand to be corrected, because someone has to pick up this sharp and pointy conversation, enter into it and swim among its thorns.

I am going to talk about whiteness.

First you should know that this is the beginning of a conversation, not my finished, end-of-story statement of opinion. In fact, this may just be the first in a series of posts about this topic.

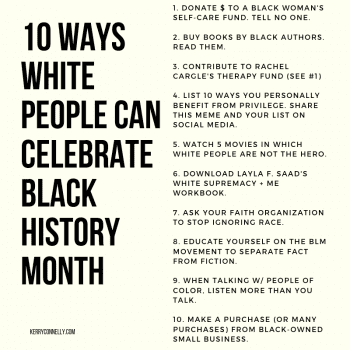

Second you should know that this was inspired by greater thinkers than me, and by a series of events in my consciousness. Back in August, when I was at Christian Theological Seminary for a weeklong intensive class called Gateway to Theological Education, we had a nice, long talk about race. As has always been the case, these discussions were enlightening, exhausting, and incredibly necessary. It’s hard to talk about race, even among people who are coming to love each other. During that conversation, we talked a lot about white privilege, about the denial of white privilege by many white people, and we talked about ways in which we can all be more aware of how institutionalized racism operates in our world.

But one woman spoke up. She is white, an attorney general for her state, and hails from Appalachia. She said (and I paraphrase), “You know, the people I come from — they will sit down with a black person and share a meal in a heartbeat. But they’re also flying the Confederate flag, because these are people who are constantly being told they are privileged, and that they need to give up that privilege. But these people are living in trailers, barely making ends meet. They don’t feel privileged. They feel like they are barely surviving, and they are thinking, What do I have that I can possibly give up? So they fly this confederate flag, and vote for Trump, because they’re afraid that what little they have will be taken away.”

She makes a point. These are the unheard voices in America who helped vote Trump into office, who go to rallies with that Confederate flag, but don’t understand why they are perceived as racist. After all, their best friend is black, and so are their neighbors, and everyone struggles the same to get by. We’re all in this together — I’ll share my meal with you, but I don’t understand when you say that I am privileged, because tomorrow, you might have to share your meal with me.

Another thing that happened is that I wrote this piece about the #TakeAKnee movement, and it was my most popular, most shared post ever. At this writing, it’s had over 38,000 pageviews, 16,000 shares, and more comments on Facebook than I can keep up with. That conversation includes the usual vitriol, but some of it is valuable. One guy said (again, this is a paraphrase), “Look, when you make a little over $200 a week, and somehow over the course of a few years manage to save enough to buy a Super Bowl ticket, you just want to go and enjoy the game. People are struggling. It’s rough out here. We just want to enjoy a game without having to see a protest.” While this comment smacks of privilege — indeed, it positively drips with the stuff — there is also an underlying sentiment that is universal to the human experience: It’s rough out there. Everyone just wants a little joy. Is that too much to ask?

If you know me at all you know that I’m far from a white apologeticist, but there’s truth in his statement, whether you’re black or you’re white. Neither whiteness nor blackness diminish a basic human desire for simple joys and pleasures. Black people very likely look at white people and think, “Your capacity for joy is a lot easier to access than mine, because you don’t have my blackness to deal with.” White people, who have neither experienced the oppression that black people have, nor do they understand how they themselves benefit from it, have heard about this thing called affirmative action which seems to be designed to punish white people for that “imaginary” oppression, and they think “Wait, I thought we were all in this together? How did I become the bad guy?”

As all of this was happening, I was also being introduced to Womanist theology — a conceptual framing that considers theological ideas through a decidedly African American woman’s lens. Reading these voices stirred something deep within me, and I was both enthralled and frustrated by these readings. Enthralled, because I related to the deep richness, the fullness of life and love and nurture and community that these thinkers described; frustrated, because it could not be for me without my appropriation of it — my unlawful ownership of it, so to speak. I was left outside of this rich landscape of thought and theology because of my whiteness. To claim it would be to exercise white power. I must instead leave it be what it will be without me, appreciate it for its beauty and gorgeous being, and stay here, in my whiteness, loving — and learning from it — from afar. This is not wrong. It is good and right that I do not get make womanist theology — something I admire and respect and yes, even love — my own. I am not whining. But I am, perhaps, grieving.

Then, I listened to this interview with Ruby Sales, for a Biblical Reflection class I am taking, and I was blown away. When she was 17, a white seminarian named Jonathan Daniels threw himself in front of a bullet, saving Ms. Sale’s life. She has since become, among other things, a public theologian, and when Krista Tippett interviewed her, she said the following, and it rocked my world:

What is it that public theology can say to the white person in Massachusetts who’s heroin-addicted because they feel that their lives have no meaning, because of the trickle-down impact of whiteness in the world today? What do you say to someone who has been told that their whole essence is whiteness and power and domination? And when that no longer exists, then they feel as if they are dying or they get caught up in the throes of death, whether it’s heroin addiction.

I don’t hear any theologies speaking to the vast amount — that’s why Donald Trump is essential, because although we don’t agree with him, people think he’s speaking to that pain that they’re feeling. So what is the theologies? I don’t hear anyone speaking to the 45-year-old person in Appalachia, who is dying of a young age, who feels like they’ve been eradicated because whiteness is so much smaller today than it was yesterday. Where is the theology that redefines to them what it means to be fully human? I don’t hear any of that coming out of anyplace today.

And we’ve got a spirit — there’s a spiritual crisis in white America. It’s a crisis of meaning, and I don’t hear — we talk a lot about black theologies, but I want a liberating white theology. I want a theology that speaks to Appalachia. I want a theology that begins to deepen people’s understanding about their capacity to live fully human lives and to touch the goodness inside of them rather than call upon the part of themselves that’s not relational. Because there’s nothing wrong with being European American. That’s not the problem. It’s how you actualize that history and how you actualize that reality. It’s almost like white people don’t believe that other white people are worthy of being redeemed.

-Ruby Sales, interviewed by Krista Tippett;

“Where Does It Hurt?” OnBeing, September 15,

2016.

I want a liberating white theology too. I want a theology that liberates white people from the chains of our supremacist past. I don’t want us to dodge our responsibility. On the contrary. I want us to live in enough freedom to own our lineage and say, “Never Again.” I want us all to have the chance to become fully human, and I’m starting to realize that oppression is a two-faced prison warden, whose chains go both ways, shackling both the oppressed and the oppressor, stealing away the humanity of each. This is not the freedom that God imagines.

The generosity of spirit and love that Ms. Sales displayed left me floored for days. I listened to this interview over and over again, and every time I was equally moved and struck by it. Leave it to God that the healing of a white patriarchal nation’s soul might come through an elderly black woman. That is exactly the kind of thing I would expect God to do.

So all these consciousness events — these tiny awakenings within me — lead me to ask a number of questions. With each synapse fire, another question arises, so this list is by no means exhaustive. But this is a list that I would like to explore over the coming weeks, and which I hope will spark more conversation on the being of whiteness. I have so many questions, such as:

What is whiteness? What is the white identity? What should it be?

Can whiteness exist apart from an identity of (false) supremacy?

What does it mean for a white person to give up their white privilege? How does one do that, in real life, practical ways?

How does white guilt operate to perpetuate racist systems? Whom does it serve?

How can we move past our shared history of guilt and the pain of believing in our false supremacy, and still not diminish the very real ramifications of our privilege and racism on people of color?

How does God want to redeem whiteness?

Can an inclusive theology exist? Must we always be separate?

Whose job is it to dismantle racism? How do we dismantle it when it’s such a big problem?

These questions — and others — are what I hope to explore over coming weeks. I hope you will think about these questions as well, and share them in the comments page or on the Jerseygirl, JESUS Facebook page. For more conversations about this and other cool stuff, pop on over to my website, and join my mailing list while you’re there, too.

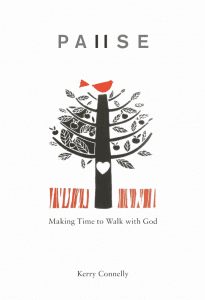

My book, PAUSE: Making Time To Walk With God is available now exclusively at Barnes & Noble. Called “A spa day for the soul,” it’s a different kind of devotional that invites you back into the garden, so you can truly experience the shalom of God. Order your copy today.

My book, PAUSE: Making Time To Walk With God is available now exclusively at Barnes & Noble. Called “A spa day for the soul,” it’s a different kind of devotional that invites you back into the garden, so you can truly experience the shalom of God. Order your copy today.