Last year, I had a conversation with a woman I’ll call Sandy.* Sandy was a coaching client of mine who is a leader in the world of progressive Christianity. She’d helped organize an event, and she and her colleagues wanted to be very intentional about including multiple voices. They know that one of the biggest problems facing Christianity today — including progressive Christianity — is the fact that so many of our conferences have all white speakers — often, all white male speakers. We like to talk the talk, but when it comes time to step aside and give up the platform to people of color, we forget our own ideology. We’re so busy talking we forget to actually do.

Sandy and her friends didn’t want that to happen, and they were successful. There was one white male speaker — a big shot kind of guy — who more than filled the space of the older white male perspective. Other voices got their time at the podium: black men and women, Latino people, and indigenous peoples were all represented. The organizers were successful in offering platform to a diverse group of speakers, and that’s great.

Except for Ray*.

Ray is a good friend of Sandy’s, an older, white man, and someone who’s used to speaking at events like this. He’s used to being asked to speak at events like this. But this time, because the big shot kind of guy was there, and they were making room for other perspectives, no one asked Ray to speak. And Ray noticed.

Now Ray wasn’t complaining. He understood why it happened, and he thought it was right and good that diversity was their goal and their priority. But he was left wondering if he had become irrelevant.

Ray’s story stuck with me for days, and I held the tension of a double-edged emotional response. On the one hand, I kept thinking, “Well, Ray, welcome to my world.” I can’t tell you how often I have felt silenced and overlooked. I have sat around conference room tables, in planning meetings, and participated in the organization of events for which I am more than qualified to speak or teach and I have never been asked. I know what that feels like, to be invisible. And let’s face it — I’m not that invisible. I tend to be a loud-mouth. I speak truth to power (it’s exhausting) and I have a platform, small as it may be. I get to be seen by some people. I can only try to imagine how people who are marginalized, who do not have the privilege that I have a as a white, educated, upper-middle class woman might feel.

But on the other hand, I think Ray had ridden this thought train right to the edge of a cliff, and dangling over the edge is the big question: What’s next? When a white person gives up their privilege, what’s next for the white person?

Until we answer this question, until we can get a grip on what that looks like, and until white people can develop an identity that allows for our full humanity without unearned privilege and pseudo-supremacy, we’re going to hold onto that privilege with a vice grip. It’ll creep into everything we do, even as we insist that we are allies and scream from the mountaintops that black lives matter.

We will most likely get much of this wrong, and we will require much grace from people of color as we attempt to plod through this hard, gritty work. But it’s incredibly important that when we get that grace, we use it well, and we use it to do better.

It’s not fun or easy to be called out for when our privilege is seeping into what we thought was the good work of dismantling injustice, but a large part of creating this new identity — and accepting grace — is in how we respond when we do. A great example of how not to respond came from Michael Hardin, the founder of the now defunct Preaching Peace conference.

After writer Kathy Khang questioned the all-white lineup of heavy-hitting progressive Christian speakers, Hardin offered an apology, but then filtered that apology through a white-washed excuse of “We couldn’t find any speakers of color.” I’m really not sure what happened there — I only heard this narrative recently and it apparently started way back in May — but Hardin eventually cancelled the conference and sent out a blistering email to everyone who had registered, blaming Kathy by name for not only the demise of the conference, but his own ruined finances, and his exit from the faith.

Would you like fries with your nice heaping plate of white male frailty?

In my mind, Hardin came to the same precipice that Ray did, but while Ray is standing there, trying to find a bridge across the crevasse (while possibly mourning the end of the road), Hardin took a flying, suicidal leap to the depths. I’m not sure I know yet the building blocks of Ray’s bridge. That’s why I’m writing about this topic — I think it’s time we start mining for the building materials of this new white identity — one that cedes power and platform, that intentionally makes room for diversity without tokenism, and that celebrates difference without appropriating it.

But one thing I do know for sure is that a temper tantrum isn’t the way to go.

While I don’t doubt that Hardin truly feels as though he has been hurt, his unwillingness to take responsibility and his trigger response to place blame on both individuals of color and the whole people group he calls “the militant progressive Christian left” tells me he’s less interested in building bridges and more interested in blowing them up. He can’t see what’s next for his white identity because he’s choosing not to look for all the pyrotechnics.

I don’t know, either, how to answer that question, “What’s next?” Are white people bound to feel irrelevant if we step aside and give the podium to other voices? Is that what giving up privilege means?

And is that whole conversation about conferences and podiums in itself privileged, when we think about the marginalized folks who not only can’t afford these conferences, but are too busy surviving to care? We in our progressive intellectualism can stand to do better there, too.

And after all our navel gazing is done, what are going to do? How will we lean into the fullness of our humanity, find our value apart from pseudo-supremacy?

And where does Jesus fit in? What does Jesus show us about this? What does Jesus tell us about our capacity for love, for justice, and for silence and podium-giving?

This is where the real work begins, I think. We must become whole human beings — and our system of white supremacy and privilege has kept us from doing that. Because we sense our lack of wholeness, we hold on to pseudo-supremacy, never realizing that something infinitely diverse and more gorgeous is dancing out there on the edges, and we only need to let go of the one in order to grasp the other.

As long as we don’t offer an alternative white identity to the ideology of supremacy that helps white people feel whole, valued, and loved apart from pseudo-supremacy, that void will always be filled with Neo-Nazism, #MAGA mindsets, and Breitbart-fueled agendas. White people need to own racism. White people need to do the work. And the work that needs to be done is on the white person’s identity as worthy in and of itself — not as an alleged “superior race” (that’s bunk), but as children of God.

*Not their real names.

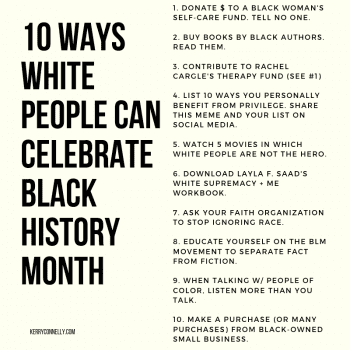

Like this discussion? Connect with me at www.kerryconnelly.com