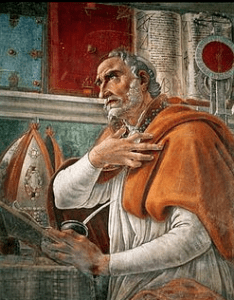

What happens to a mathematician or science-type who decides out of curiosity to spend gobs of time — weekends, conferences, reading time — with the creationists? Their number, as the recent Gallup poll indicated (though this book refines those numbers a bit), is not small. What happens when you spend time with creationists? Jason Rosenhouse, a professional mathematician, did just that and wrote up a book about it. His book is called Among the Creationists: Dispatches from the Anti-Evolutionist Front Line (Oxford Univ Press, 2012). It’s a good read; it’s an alarming read at times; it’s an attempt at comprehending creationists; it’s by an atheist, an evolutionist, and someone who has a hobby of wondering what makes creationists tick. He’s deeply bothered by the approach — and Rosenhouse’s opening encounters are illustrated by this cartoon to the right.

What happens to a mathematician or science-type who decides out of curiosity to spend gobs of time — weekends, conferences, reading time — with the creationists? Their number, as the recent Gallup poll indicated (though this book refines those numbers a bit), is not small. What happens when you spend time with creationists? Jason Rosenhouse, a professional mathematician, did just that and wrote up a book about it. His book is called Among the Creationists: Dispatches from the Anti-Evolutionist Front Line (Oxford Univ Press, 2012). It’s a good read; it’s an alarming read at times; it’s an attempt at comprehending creationists; it’s by an atheist, an evolutionist, and someone who has a hobby of wondering what makes creationists tick. He’s deeply bothered by the approach — and Rosenhouse’s opening encounters are illustrated by this cartoon to the right.

The book opens with some Vignettes and then turns to reports about some conferences: the Creation Mega-Conference at Lynchburg, the Darwin vs. Design Conference in Knoxville, the Creation Museum, and the 6th International Conference on Creationism in Pittsburgh.

Creationism has many meanings, and we’ll get to his definition next post, but in general it refers to people who believe science conforms to a kind of reading of Genesis 1-2 (traditional, literal, etc). What bothers you most about this approach? Do you think his sketch is typical? What are your experiences with the creationists? How pervasive is this approach in home-schooling? Do you think there is a disposition against the scientific facts here?

We’ll not understand ourselves well until we understand what outsiders encounter; so whether you are a Young Earth Creationist or a creationary evolutionist (theistic evolution) … if you believe the Bible as God’s Word, then this book is worth reading. Why? We might call it mirror reading of the evangelical science-faith conversation.

In 2000 Rosenhouse attended a religious home-schoolers conference on education, and one of his first impressions: “from their perspective, evangelical Christianity was a tiny island of righteousness adrift in a sea of secular evil” (3-4). They were, in effect, in a “war zone” (4). He encountered Ken Ham who made some forays into mathematical theories of probability and information, Rosenhouse’s field for his PhD and academic work. Rosenhouse: “his arguments ran afoul of certain basic facts” (4). So he had a conversation with Ham that also went afoul, including Rosenhouse reporting that Ham called him “arrogant.” Rosenhouse: “I replied that arrogance was standing on a stage pretending to know something about science” (4).

Rosenhouse is irritated when conservative Christians lecture publicly about public school and secularism indoctrinating students. He also observes that “creationism’s most notable failures have come in the courtroom and the seminar hall” (5) — why? In those settings what matters is where the evidence takes us. He contends creationism devotes attention to judges and professors because those are the settings it struggles to keep up.

He tells of a long conversation at a subway with an adult woman and three teenagers. He also attended an evening with Luis Palau, and then the Dartmouth student newspaper had a big battle over these issues … and Rosenhouse was snagged into the debate. Here are some elements of the creationists game that bother him:

1. Evolution is “ridiculous” and there is “no evidence” for it and “massive, irrefutable evidence” for YECreationism — leading to this: “Evolution… was not even about science at all. It was about promoting the religion of secular humanism” (18). In other words, science is caught up into (colonized by) another narrative about belief vs. unbelief.

2. Scientists, most of them, have gotten it completely wrong. “It is one thing to suggest that the scientists are wrong, but it is quite another to suggest that they are stupid or have overlooked simple errors” (18). As a professor, I’d like to make a simple but penetrating point: young scholars feast on making their mark by offering some contribution to knowledge; if the basics of evolution were wrong, the young scholars would feast on it because they could make their contribution. Don’t forget that: this stuff is being checked day in and day out.

Rosenhouse has problems with religion. He is an atheist, which doesn’t mean he is “metaphysically certain there is no God” or that he wallows in nihilism or moral relativism (standard observations among the creationists because the slippery slope argument is used so often). What are his problems?

1. It is very difficult to square evolution with a Christian view of the world.

2. Science has not found any evidence of an intelligent designer.

3. He believes in a kind of knowledge based on evidence and only on evidence, which means he’s got the typical scientific, mathematical skeptical approach.

This all means he wonders what religious folks know that he can’t find access to. Other issues:

1. The cultural and social dimensions, fine; ritual and tradition, fine; disposition toward nature, fine.

2. Problems: adherence to doctrine; the Bible as the Word of God and he sees little different in the Bible than other sources; how can religion justify its knowledge? The ease with with people speak of God; God’s foreknowledge and human free will; explaining things with God leads to problems with God. The moral argument doesn’t work: not all believers are good; some nonbelievers are good; some societies that pervasively are nonbelieving are happier and have more goodness.

But the smart people who believe make him pause; he wants to comprehend this stuff.

Thus, his confession: “Atheism just makes the fewest demands on my credulity” (24).