Ed Stetzer had an interesting post on his blog last week – 3 reasons for Christians to Engage in Science. This post is a reprint of an essay he wrote for a small booklet recently released by the National Association of Evangelicals: When God and Science Meet and available for free download. The booklet includes essays by John Ortberg, Mark Noll, Christopher Wright and more.

Ed Stetzer had an interesting post on his blog last week – 3 reasons for Christians to Engage in Science. This post is a reprint of an essay he wrote for a small booklet recently released by the National Association of Evangelicals: When God and Science Meet and available for free download. The booklet includes essays by John Ortberg, Mark Noll, Christopher Wright and more.

Stetzer’s three reasons (read his essay on his blog or in the booklet for his elaboration of these points, bold added):

First, creation speaks to a creator. Because we know there is a creator, we should be the ones most concerned about his creation. …

In Romans 1, Paul points out that attributes of God are made clear in creation. We can know his eternal power and divine nature, because they have been clearly seen since the creation of the world.

If Scripture says creation, and therefore the sciences that explore it, point to God, why would we run away from that? We, above all others, should love, study, explore, examine and care for the creation that provides evidence of God and his character.

Second, dismissing science undermines our witness. But many evangelicals are backing away from science. In a society driven by scientific achievement, it is unwise and counterproductive to our mission for Christians to embrace an anti-science label.

Third, science can better society. … The fact is, as we find better ways to farm, powerful new medicines to heal and more effective ways to power our society, the poor benefit, societies are transformed for the better and the world looks and is more of what God intended it to be.

Christians are to champion the good of their city and society as a whole. Leveraging scientific study and achievement for the betterment of people is an entirely Christian thing to do.

All three of these are great reasons for Christians to engage in science. The pursuit of science brings a sense of wonder, beauty, and awe to many scientists, religious or not. For a Christian in the sciences there is an added wonder and beauty. When we, as scientists, study the “natural” phenomena of the universe, whether in physics, chemistry, paleontology, geology, biology or some other science, we are studying the nature of God’s creation. This can make the pursuit of scientific understanding a form of worship as Dorothy Chappell, Dean of Natural and Social Sciences at Wheaton College, says in her essay:

Scientists can discover, study and contemplate the complexities of the created order while apprehending God’s glory, which remains resplendent throughout the creation; in other words, they can worship and interact with God as they do their own professional work. This represents a profound discipline: doing good science and practicing vibrant faith. A natural outcome that results when scientists explore the mysteries of creation from a biblical worldview is a greater capacity for wonder, awe and humility. These, after all, are the traits of effective scientists and devout Christians. (p. 36, When God and Science Meet)

Stetzer’s third reason is also highlighted in a number of the essays in When God and Science Meet. The pursuit of science is transforming the world for the better. This isn’t to embrace the myth of human moral progress where human effort will produce a perfect society or bring the Kingdom of God. It is simply to state a fact – vaccinations, sanitation, clean water, efficient transportation, medicines, instrumentation for imaging and diagnosis, all of these and many more developments, have made life for many longer, healthier, and safer. “Leveraging scientific study and achievement for the betterment of people is an entirely Christian thing to do.”

Finally his second reason, which is undervalued or misinterpreted by many: Dismissing science, or worse yet distorting and misrepresenting science, undermines our witness as Christians in profound ways. The church needs Christians engaged in science to hold fellow Christians to a high standard and to provide the needed expertise and review. John Ortberg notes in his essay:

I have seen too many young people in too many churches exposed to bad science in the misguided idea that someone was defending the Bible; then they go off to college and find out they were misinformed and they think they have to choose between the Bible and truth. (p. 28)

Bad science does no one any good. Not Christians adults or youth, and certainly not non-Christians who find bad science a reason to dismiss any need to dig deeper and understand Christian faith. We need to pursue the truth.

Christian faith and the study of science are not mutually exclusive pursuits. Taking the Bible seriously does not mean holding to positions clearly contradicted by modern science. The Bible is not a science book. Taking the Bible seriously does call us to stand against the metaphysical conclusions that some draw from science, just as it calls us to stand against the “wisdom of the world” driven by the pursuit of money, sex, and power.

The pursuit of scientific understanding has unearthed a wealth of new information. Information that our predecessors had no knowledge of and did not need to wrestle with … the vastness of the universe, the age of the earth, evolution. The church today does need to wrestle with this data. In order to do this we need people who are conversant in science, who will take the time to explain the data and explore the relationship between the new insights from science and Christian theology. One of the reasons we need Christians to engage in science is to lead the church faithfully into the future.

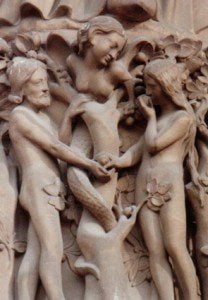

And this leads to Adam. If that seems like a sharp left turn, changing the subject, it shouldn’t. Every discussion of science and Christian faith these days seems to return to the question of Adam, human evolution, and common descent. This is an overstatement, but not by much. Many of my posts over the last several years have turned around the discussion of Adam. In general I’ve focused on the biblical and theological issues because, quite frankly, I am convinced by the evidence of common descent. As a result I am deeply interested in the ramifications this has on our understanding of life from a Christian perspective.

And this leads to Adam. If that seems like a sharp left turn, changing the subject, it shouldn’t. Every discussion of science and Christian faith these days seems to return to the question of Adam, human evolution, and common descent. This is an overstatement, but not by much. Many of my posts over the last several years have turned around the discussion of Adam. In general I’ve focused on the biblical and theological issues because, quite frankly, I am convinced by the evidence of common descent. As a result I am deeply interested in the ramifications this has on our understanding of life from a Christian perspective.

Many readers, however, remain unconvinced that a unique couple is disproved by the scientific data. We need Christian scientists with the expertise and patience to explain the scientific data and consensus on a level accessible to non-scientists and to point out both the strengths and the weaknesses of the data and interpretation. I haven’t the patience (or the ready expertise in genetics) to offer a coherent and accessible explanation on common descent and human genetics. Fortunately Dennis Venema, professor of biology at Trinity Western University in Langley, British Columbia, has the patience, expertise and ability. Dennis is in the middle of a long series of excellent posts at Biologos exploring Adam, Eve, and human population genetics.

The last few installments of Adam, Eve, and human population genetics have looked at the arguments Dr. Vern Poythress advanced in his recent short book Did Adam Exist?. Dr. Poythress’s scientific argument leaves much to be desired. He misinterprets the scientific papers he uses to defend his position that common descent is unsupported by the genetic data and that science cannot rule out a bottleneck consisting of one unique human couple as progenitor of the entire human race. Dennis does an nice job of pointing out the problems with Dr. Poythress’s scientific argument. Bad scientific arguments are far too common and do devastating damage to the faith of far too many. (See John Ortberg’s quote again.)

We need Christians like Dennis, engaged in science and with a heart for the church.

Why should Christians engage in science?

Do Stetzer’s reasons ring true? What might you add to the list?

How should Christians respond to the challenges raised?

If you wish to contact me, you may do so at rjs4mail[at]att.net.

If interested you can subscribe to a full text feed of my posts at Musings on Science and Theology.