Kris and I were in Vancouver for seven days where I was teaching at Regent College in the mornings, and we spent the afternoons visiting a number of places — what a beautiful city! — but more about Regent and Vancouver on another day. All this to say, not much when it comes to Meanderings… sorry. But here’s four choice items.

Pamela Wood: “On Maryland’s Eastern Shore, a previously untold story of free African Americans is being told through newly discovered bits of glass, shards of pottery and oyster shells. Piece by piece, archaeologists and historians from two universities and the local community are uncovering the history of The Hill, a part of the town of Easton believed to be the earliest community of free blacks in the United States, dating to 1790. It also could have been the largest community of free blacks in the Chesapeake region. During the first census in 1790, about 410 free African Americans were recorded living on The Hill — more than Baltimore’s 250 free African Americans and even more than the 346 slaves who lived at nearby Wye House Plantation, where abolitionist Frederick Douglass was enslaved as a child. Free African Americans in Easton lived alongside white families, said Dale Green, a Morgan State Universityprofessor of architecture and historic preservation who is working with the University of Maryland‘s Mark Leone on the Hill project. “It’s not just a black story. It’s an American story,” Green said.”

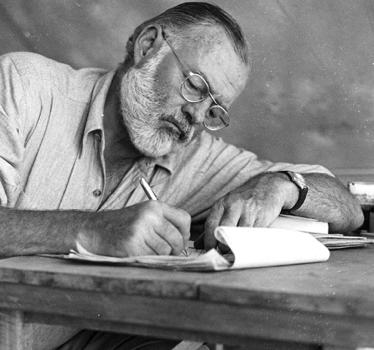

Olivia Laing, on the alcoholism of great writers, a long essay worth your time: “In order to understand how an intelligent man could get himself into such a dire situation, it’s necessary to understand what a glass of champagne or shot of scotch does to the human body. Alcohol is both an intoxicant and a central nervous depressant, with an immensely complex effect upon the brain. A single drink brings about a surge of euphoria, followed by a diminishment in fear and agitation caused by a reduction in brain activity. Everyone experiences these effects, and they are the reason alcohol is such a pleasurable drug; the reason why, despite my history, I too love to drink.

Olivia Laing, on the alcoholism of great writers, a long essay worth your time: “In order to understand how an intelligent man could get himself into such a dire situation, it’s necessary to understand what a glass of champagne or shot of scotch does to the human body. Alcohol is both an intoxicant and a central nervous depressant, with an immensely complex effect upon the brain. A single drink brings about a surge of euphoria, followed by a diminishment in fear and agitation caused by a reduction in brain activity. Everyone experiences these effects, and they are the reason alcohol is such a pleasurable drug; the reason why, despite my history, I too love to drink.

But if the drinking is habitual, the brain begins to compensate for these calming effects by producing an increase in excitatory neurotransmitters. What this means in practice is that when one stops drinking, even for a day or two, the increased activity manifests itself by way of an eruption of anxiety, more severe than anything that came before. This neuroadaptation is what drives addiction in the susceptible, eventually making the drinker require alcohol in order to function at all.

Not everyone who drinks, of course, becomes an alcoholic. The disease, which exists in all quarters of the world, is caused by an intricate mosaic of factors, among them genetic predisposition, early life experience and social influences. As it gathers momentum, alcohol addiction inevitably affects the drinker, visibly damaging the architecture of their life. Jobs are lost. Relationships spoil. There may be accidents, arrests and injuries, or the drinker may simply become increasingly neglectful of their responsibilities and capacity to provide self-care. Conditions associated with long-term alcoholism include hepatitis, cirrhosis, gastritis, heart disease, hypertension, impotence, infertility, various types of cancer, increased susceptibility to infection, sleep disorders, loss of memory and personality changes caused by damage to the brain. More stress, of course: to be drowned out in turn by drink after drink after drink.

George Will on Detroit: “Here, where cattle could graze in vast swaths of this depopulated city, democracy ratified a double delusion: Magic would rescue the city (consult the Bible, the bit about the multiplication of the loaves and fishes), or Washington would deem Detroit, as it recently did some banks and two of the three Detroit-based automobile companies, “too big to fail.” But Detroit failed long ago. And not even Washington, whose recklessness is almost limitless, is oblivious to the minefield of moral hazard it would stride into if it rescued this city and, then inevitably, others that are buckling beneath the weight of their cumulative follies. It is axiomatic: When there is no penalty for failure, failures proliferate.

This bedraggled city’s decay poses no theological conundrum of the sort that troubled Darwin, but it does pose worrisome questions about the viability of democracy in jurisdictions where big government and its unionized employees collaborate in pillaging taxpayers. Self-government has failed in what once was America’s fourth-largest city and now is smaller than Charlotte.”

Nikki Toyama-Szeto:”How do we as women steward power well?

For one thing, I think it is really important for women to embody their leadership. Because so many of our leadership models are male-based, women don’t necessarily embody it in their own selves. They try to dress differently. They try to, in a sense, operate cross-culturally, the culture being cross-gender, in order to be effective. And I think sometimes that is appropriate, but I really appreciate work such as MaryKate Morse’s work on women and embodied leadership, knowing the space you take up, knowing the impact your space has on other people. I think that’s all part of power, understanding and knowing within your own self what is the power that you have, and also the source of that power. Some of it is God-given authority, some of it is positional authority, some of it is authority that we’re given because of our education, our economics, our fluency in English, etc.

And then, I think, trying to grapple with how you steward it. I have come to understand that leadership is more about other people’s experience of my presence, and the impact that my presence has even when I’m not there. I think a good litmus test for someone who is using power well, as reported in Lean In, is when you’re gone, do people feel less oppressed, a greater sense of freedom, or — the language I like to use is — does my presence bless people? Or is my presence a hardship?

There are also cycles of power we need to recognize. It’s very interesting to look through a Christian lens — there’s having power, there’s giving up power, and then there’s claiming power. Some of it depends on where you are in that circle, what the faithful response to power is. So in some cases, if you have power, the faithful response is actually to relinquish power or to use your power for somebody else. And then in other cases, when you’re disempowered, the faithful response is actually to step and to claim power. For example, trying to step into Shalom. Our world is broken and you might actually need to step in and say, this isn’t right. It is important for women in power to understand what of the power they have is theirs to give away, where do they need to take that power and step in and claim more– possibly for their own self or for a greater thing such as the health of their organization — and where do they just need to steward the power that they have.