What were the 1950s like? Maybe we should rework that question to What was the future’s hope as expressed in the 50s? George Marsden: The 50s were in continuity with the American Enlightenment in the hope or belief that “a coalition of cultural leaders, including some religious leaders, despite their differences, could somehow guide the society toward a progressive, enlightened, and humane cultural consensus” (xxiv), from The Twilight of the American Enlightenment.

What were the 1950s like? Maybe we should rework that question to What was the future’s hope as expressed in the 50s? George Marsden: The 50s were in continuity with the American Enlightenment in the hope or belief that “a coalition of cultural leaders, including some religious leaders, despite their differences, could somehow guide the society toward a progressive, enlightened, and humane cultural consensus” (xxiv), from The Twilight of the American Enlightenment.

I want to draw out some ideas in this new book by Marsden, but what follows is more notes from the book than a review or an evaluation.

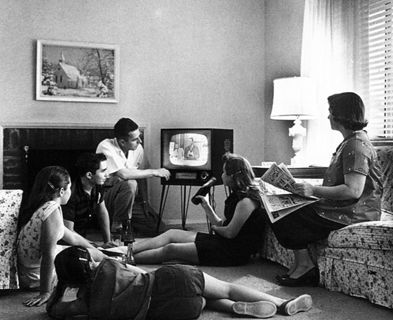

The 50s, under serious challenge by mass media and technology, then were hanging on to an American Enlightenment ideal where the cultural elite (public intellectuals) and a consensus would lead the nation toward a better society. The 60s and onward to one degree or another shattered that “consensus” toward pluralism and identity politics.

Mass culture challenged the 50s hegemony of culture, and while many thought the nation was sinking into an abyss of ignorance, others (like Edward Shils) thought there was still room for hope. What happened in the major exchanges, however, now very clear, was the belief that “intellectuals and artists” would provide “cultural leadership” (15). The imperial West was still the mood but within the generation that vision collapsed. A ruling theme, however, was that of anti-intellectualism, a la Richard Hofstadter (and Mark Noll picked up this theme in some of his writings in the 90s), and that the golden age of the founders was coming to a crashing halt.

Marsden’s romp through the 50s takes us into the heart of some fascinating scholarship — scholarship that fought for freedom as autonomy and opposed conformity. (If you are old enough, think Marlboro man.) He dips in and out of Erich Fromm’s alienation theme in Escape from Freedom, David Riesman’s phenomenally successful The Lonely Crowd who focused on three kinds of humans: tradition-, inner-, and other-directed. The latter group let mass culture (TV) shape their identity while the second one pursued genuine freedom. Then came William Whyte’s The Organization Man, where corporations were swallowing humans whole — the heroic individual resisted. (Advertising’s influence was under examination, too.) And Betty Friedan challenged male hegemony and new themes were beginning to take shape that would alter the course of the 20th Century.

Walter Lippmann, in his famous Essays in Public Philosophy, argued that the liberal elites had already destroyed the foundations upon which their cultural leadership was built. The future was natural philosophy. What was left was “gentlemanly constructive pragmatism” (50-51). All of this led to an empirical theory of naturalism but a convenient, cultural-leadership-propping faith in the current cultural moral (and progressivist) consensus.

The whole was undone by a doctrine of toleration’s achievement of diversity at all levels, even calling it at times identity politics, and an epistemology constrained by the scientific method that turned religion into the private world. Pragmatism ruled but natural law and the Enlightenment was the tradition. Arthur Schlesinger, Jr, set his hopes for racism on education. Niebuhr was less optimistic; he sketches the contribution of ML King Jr (who had a theistic foundation for his morals, a foundation rejected by most).

Marsden’s driving aim is to show two driving elements of America’s culture: the authority of the scientific method and the authority of the autonomous individual (69). The emergence of psychology, and of course he sketches Skinner’s determinism themes in behaviorism. On to Benjamin Spock and the critique of narcissism by Nicholas Lasch.

Marsden turns then to religion: Henry Luce (a growing pluralism) … to civil religion… and the importance of Reinhold Niebuhr’s realism, and Marsden’s sees Niebuhr’s subjective elements as making religion ultimately optional. At the same time one begins to see a kind of inclusive pluralism, a consensus-shaped faith that is pluralistic. Theology was combined with progressivism.

American pragmatism erodes when the shared moral capital dissipates. The drive to take America back was too much an attempt to return to the consensus of the 50s. Marsden ably sketches the rise of the Moral Majority or Religious Right, though I think he ignores the Bob Jones interracial dating issue. He drives issues toward the articulations of Francis Schaeffer.

Pluralism was the name of America’s game by the time the 60s had their influence. How can a variety of religious voices find a mainstream discourse? Marsden finds hope in the Kuyper shaped culture of the Netherlands, to confessional pluralism or to principled pluralism and Kuyper’s vision of “common grace” is a place for Marsden to begin. It is not a little ironic that he finds hope in the very place that has eroded — academia where pluralism, and not at all one like Kuyper’s, reigns. Yet, Marsden’s hope is academic pluralistic interaction.