I’m an Apple guy. My first computer was a Macintosh Classic. That beige little box of magic allowed me to get on the World Wide Web for the first time, open an AOL account and send my first email. All of which happened circa 1991 for about $1000. I had no idea what I was doing, even less about what I was getting into. However, I learned an invaluable lesson. Apple provided me a safe and stylish means through which I could cautiously enter the scary unknown wilderness that was (and still is) the “new world” of technology. Apple let me earn my “merit badge” in personal computing and I’ve been loyal customer ever since. (There was that short experiment with Windows in college, but let’s not go there.)

I’m an Apple guy. My first computer was a Macintosh Classic. That beige little box of magic allowed me to get on the World Wide Web for the first time, open an AOL account and send my first email. All of which happened circa 1991 for about $1000. I had no idea what I was doing, even less about what I was getting into. However, I learned an invaluable lesson. Apple provided me a safe and stylish means through which I could cautiously enter the scary unknown wilderness that was (and still is) the “new world” of technology. Apple let me earn my “merit badge” in personal computing and I’ve been loyal customer ever since. (There was that short experiment with Windows in college, but let’s not go there.)

For me and countless others, Steve Jobs was the technological prophet that led us into the freedoms this new world offered. Over time, despite the hiccups here and there, the Newton being one, he kept pulling back the curtain on the possibilities of this promised land. I didn’t have to know anything about computers to use my Mac. I still don’t. That’s why I’ve now got more Apple devices in my home than any other product brand….save Hanes underwear. Jobs and Woz made great products. And they left a trail of great ideas for their progenitors to follow. All of this to say….I’m an Apple guy.

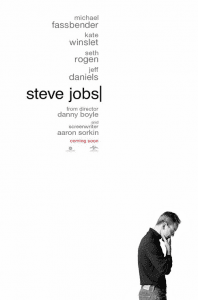

So, it has been with great lament that since Jobs’ death my naiveté about the man behind these great products is dying a hard and difficulty death. Jobs, it turns out, lived a life much more comparable to Machiavelli than Michelangelo. As a longtime fan of Aaron Sorkin’s work I eagerly anticipated how this gifted writer would portray the complexity and brilliance of one of my generations most iconic characters. I wasn’t disappointed with Steve Jobs. In anticipation of the movie I also picked up a copy of Walter Isaacson’s biography of Jobs and recently watched Alex Gibney’s well researched documentary The Man in the Machine. I’m not surprised that what Sorkin, Isaacsson and Gibney each focus on in their own unique ways is the extreme juxtaposition between the public persona and the private reality of Jobs personal character. What we learn in gritty detail is that there wasn’t a very good man standing behind a slew of great products.

Sorkin highlights this reality with a script that is equal parts profundity and poignancy matched only by Michael Fassbender’s unblinking portrayal of Jobs’ narcissistic intensity. As we have come to expect, Sorkin places his characters in a plethora of moral dilemmas that reveal their conflicted, duplicitous, and yet wounded humanity. These agonizing human histories come to the audience at a sometimes-dizzying pace as the camera follows the actor’s “walking and talking” around the set. You know when some weighty interaction is about to occur because everything comes to a stand still while we watch a blazing toe to toe delivery of rhetoric that would tongue tie an auctioneer. Sorkin is at his best when his characters discover and un-muzzle their subconscious drives and fears. These are thoughts and feelings most of us experience, but few will ever articulate them as accurately or courageously as Sorkin’s pen.

This is especially true of Sorkin’s portrayal of Jobs. We should think deeply about Jobs’ choices and worldview. If, like Jobs, I had to choose one dialog that might make a significant dent in the universe, I would select the confrontation with Jobs and Wozniak (Seth Rogen) in the third act. Jobs and Woz stand together not so much as enemies but as two halves of the American conscience as they air their very old and long suffering laundry in front of a sparse crowd of not so shocked postmodern, pre- millennial on-lookers. It’s the highlight of the movie in part because of the hauntingly crucial question they bring to the fore, and which is currently floating across our national consciousness. “Can a great person also be a good person?” Is this still possible in America? In the world? Do we even care? The importance of answering this question well is as crystal clear as my new MacBook Air Retina screen. This is certainly not a new question. Moral philosophers such as Aristotle and Xenophon would likely cock their olive wreathed heads to the side and wonder out loud if we’d lost the entire plot of life. Ancient Jewish writers and rabbis would suggest not knowing the answer to such a question reveals one is perilously close to losing one’s soul. New Testament Gospel writers pointed to the example of Jesus as one who answered that question, with a flourish, once and for all. Yet here we are, in the most technologically advanced, educated, prosperous, and liberated societies in the world, with no clear consensus on this most basic of human issues.

What Jobs’ life and legacy reveal is that we don’t have much of an idea of what a higher good is, or the common good. We do however, have a very good grasp of what consumer goods are along with what is “good” for me. Life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness has, for a while now, been increasingly translated to pertain to only “my” life, “my” liberties, and “my” happiness. Jobs is the poster boy for the “me” life. He made amazing, life changing products. But it is also true that his legacy suggests he did not live a heroic life, one that we would want our children to model. Jobs seems to have lost the idea of what human greatness requires. Perhaps he was too busy trying to change humanity and human existence with great inventions. It seems he forgot what it was to love and be loved in the process. That’s not good. It’s a tragedy. Just ask his daughter. The ends do not justify, validate or forgive the means. The journey matters. Alice in Wonderland taught us that how we travel is often where we will arrive.

When we watch and discuss the recent presidential debates, it seems we are now as willing as ever to turn a blind eye to the means our leaders will employ as long as the end is to our liking. With the rising popularity of certain candidates that lack even the most rudimentary levels of respect and civil decorum , it may be that as a people we are now choosing to live in a political reality where image⎯not moral character and substance⎯ is all that matters. Isaacson calls this a Machiavellian-esque “reality distortion field” that caused Jobs used to distort the truth and which caused himself and others enormous degrees of suffering and pain. Reality simply doesn’t bend that easy. Even for Steve Jobs.

There is no doubt that under Jobs tenure Apple made a beneficial impact on a large portion of our world and nudged us closer to the common good. But somewhere he became unmoored, untethered from the simple but profound truth that making goods, selling services and accumulating money is not the same as possessing virtue, moral knowledge, goodness, truth and love. Somehow he was, and perhaps we are becoming a people more and more willing to trade the idea of accumulating “goods” for that ancients thought of as the eternal concept of “the Greater Good.”

Sorkin and his team have written a wonderful postmodern morality play. Our ancient Greek forbearers, along with the gospel writers and Shakespeare would be pleased at this effort. Jobs life, triumphs and tragedies present us an opportunity to inspect our own moral choices. His life provides us with the gift of a window to consider what it might be like to attain the whole world, and yet lose everything that deeply matters. He gives us the opportunity to stop for a little while and think about more than the price of Apple’s stock, or how we can upgrade as soon as possible to the new iPhone but instead contemplate the value of our soul, what we gives our lives to, what is important to us and why.

Many will say Job’s legacy is found in his unparalled aesthetic genius. Others will say it was his ruthless devotion to push the boundaries of conformity. I wonder if his greatest contribution may be the institutionalization of the slogan “think different” which remains the sustaining mantra that not only drives Apple’s product development but maintains the ethos of Apple’s sizable customer base. Others will honor his audacious confidence that one person can still change the world. All of these are sizable contributions, but would any of these traits alone make one a hero? A person to he emulated and exemplified to future generations? Can a great leader be a good person? Is there any other way?

Under Jobs’ creative mastery Apple has helped untold millions navigate the stormy waters of the technological revolution. But he won’t be helping me look to the future in order to traverse the larger existential journey of seeking true meaning and significance for my life. In fact he did just the opposite. He sent me back to the oldest, and most enduring truths of human knowledge. There is no substitute for a virtuous character. Virtue starts and ends with the human heart radically devoted to the highest good. That is something no technological revolution will ever change. In the end, the movie both literally and figuratively leaves it a bit fuzzy how Jobs’ life ended. I think Sorkin and director Daniel Boyle seems to lean toward with the sage wisdom of the likes of Jesus and Aristotle. Humanity’s greatest potential is realized in the courage to face the truth, the hope of redemption, and the unspeakable joy that comes from loving others as oneself. This is the stuff of which heroes are made.

There’s still no app for that.

-Gary Black, Jr. PhD.

Asst. Professor of Theology and Contemporary Culture, Azusa Pacific University