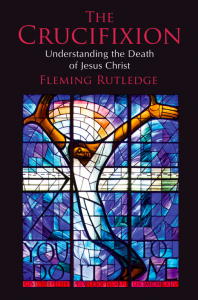

Jason Micheli will be posting reflections on Fleming Rutledge’s new book, The Crucifixion: Understanding the Death of Jesus Christ, through Lent. Jason is a United Methodist pastor in DC who blogs at www.tamedcynic.org

Jason Micheli will be posting reflections on Fleming Rutledge’s new book, The Crucifixion: Understanding the Death of Jesus Christ, through Lent. Jason is a United Methodist pastor in DC who blogs at www.tamedcynic.org

Preaching on Psalm 51 this Ash Wednesday, I noticed something as I followed along with the lector from the pew bible open on my lap. David’s indulgent confession of sin in Psalm 51 ends with this startling moment of recognition:

‘…for you [God] have no delight in sacrifice; if I were to give you a burnt offering, you would not be pleased. The sacrifice acceptable to God is [only] a broken spirit; a broken and contrite heart, O God, you will not despise.’

Surely this is a stunning epiphany to anyone who knows the Old Testament wherein sacrifices are frequent, systematized, and not only a delight to the Lord but prescribed by the Lord himself from Mt. Sinai. Consider even the remarkable dissonance- what I discovered Ash Wednesday only because my pew bible was open flat on my lap- of Psalm 51 with the psalm that immediately precedes it:

‘Those who bring their thanksgiving sacrifice [as commanded in Leviticus] honor me…’

Declares God, in Psalm 50.

Israel’s prophets, who come after David and voice God’s judgment upon the greed and false piety of David’s heirs, introduce an even more virulent strain into the bible’s thinking about the necessity and merit of sacrifice. The Christian Old Testament ends with the prophet Malachi heaping scorn upon sacrifices offered in vain, and the angry prophet of the rural poor, Amos, most famously announced God’s wrath thusly:

‘…you that turn justice to wormwood, and bring righteousness to the ground!

…the Lord is his name, who makes destruction flash out against the strong, so that destruction comes upon the fortress.

For I know how many are your transgressions, and how great are your sins—you who afflict the righteous, who take a bribe, and push aside the needy in the gate. Therefore the prudent will keep silent in such a time; for it is an evil time. Alas for you who desire the day of the Lord!

Why do you want the day of the Lord? It is darkness, not light; as if someone fled from a lion, and was met by a bear; or went into the house and rested a hand against the wall, and was bitten by a snake.

Is not the day of the Lord darkness, not light, and gloom with no brightness in it?

I hate, I despise your festivals, and I take no delight in your solemn assemblies.

Even though you offer me your burnt-offerings and grain-offerings, I will not accept them; and the offerings of well-being of your fatted animals I will not look upon.

Take away from me the noise of your songs. I will not listen to the melody of your harps. But let justice roll down like waters, and righteousness like an ever-flowing stream.’

Those last lines abut justice are familiar to us from Dr. King’s sermon on the National Mall, but excised from their original context they lose their punch and, I suspect for white Christians, turn Amos from a prophet of judgment into a dispenser of vague liberal hope.

For anyone with ears to hear, there is this unresolved tension running throughout the Old Testament as to whether sacrifice is something that God in any way desires or requires.

What do Christians make of this ambivalence regarding sacrifice when we consider what we consider the ultimate sacrifice, Christ’s expiatory offering of suffering and death upon the cross?

Is God’s self-giving in the Son through the Spirit pleasing to the Father, as the poet of Psalm 50 might imagine? Or is the murder of an innocent scapegoat upon a cross but another example of what Amos decries as the status quo’s practice of turning justice into wormwood? Worse, would God look upon us, who turn such an injustice as the crucifixion into a pleasing, even necessary sacrifice, and thunder ‘I hate, I despise, your worship?’

Reading Fleming Rutledge’s new book, The Crucifixion: Understanding the Death of Jesus Christ, I thought of observations from Marilynne Robinson, in her essay Metaphysics from her new book The Givenness of Things.

Robinson writes:

‘I know the Bible interprets Christ’s passion as expiatory, the world’s suffering as the consequence of sin, for which Christ is a guilt offering. I note as well that when God speaks through the prophets about sacrifice he treats it as the expression of a human need he tolerates rather than as anything he desires.

Certainly the death of Christ has been understood as expiation for human sin through the whole length of church history, and I defer with all possible sincerity to the central tenets of the Christian tradition, but as for myself, I confess that I struggle to understand the phenomenon of ritual sacrifice, and the Crucifixion when explicated in its terms. The concept is so central to the tradition that I have no desire to take issue with it, and so difficult for me that I leave it for others to interpret. If it answered to a deep human need at other times, and it answers now to other spirits than mine, then it is a great kindness of God toward them, and a great proof of God’s attentive grace toward his creatures.

I do not by any means doubt the gravity of human sin or question our radical indebtedness to God. I suppose it is my high Christology, my Trinitarianism, that makes me falter at the idea God could be in any sense repaid or satisfied by the death of his incarnate self.’

Is our thinking, I wonder in Holy Week, that Christ’s cross is a necessary sacrifice for sin a ‘kindness’ God permits because, though God hates all devotion devoid of any concern for justice, it’s just this offering, needful or not, that delivers what God truly desires: a broken and contrite heart?