What does it mean to be “Nicene”?

I am not a patristic scholar and I make no suggestion of it in what follows but, rather, I want to sketch the conclusions of one who is: Lewis Ayres, in his exceptional study Nicaea and its Legacy: An Approach to Fourth-Century Trinitarian Theology. Ayres’ work is intense, specialized, academic and widely acclaimed. I highly recommend it and I recommend that you savor it by reading it slowly.

First, I have not seen this but let me offer this just to illustrate the larger point: we might distinguish Nicea from Nicene. Which is to say, The Council of Nicea that produced the Nicean Creed of 325 is not the same as the later more mature Nicene theology that required more than a little battle of ideas, exegesis, and politics — which is to say, Nicea of 325 needed the Constantinopolitan Creed of 381 (at St Eirene’s) and beyond. I’ve not seen anyone distinguish “Nicean” from “Nicene” so I’m only using these terms this way to illustrate the important gap between 325 and 381 and beyond. Many were “Nicean” but were not “Nicene” (homoians, homoiousians).

Lewis Ayres calls of this fuller theological development “pro-Nicene” theology and it is quite different from its rivals who at times had the upper hand in church, in theology, and in politics (Arians, Homoians, and Homoiousians). The latter, as I read Ayres, are marked by distinguishing Father, Son and Spirit while the pro-Nicenes focus on the irreducible unity of the Godhead.

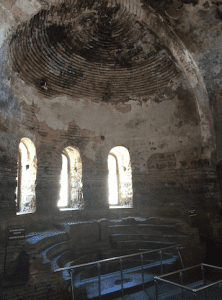

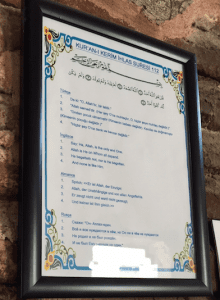

I attach here pictures from our recent trip to Nicea. The council was held in Constantine’s summer palace, now submerged in the beautiful river, and not in the church in Nicea that was built around the same time but which is now a mosque.

Lewis Ayres, following a complex discussion of the ins and outs and ups and downs of the history of how Nicene (pro-Nicene) theology developed, speaks of the Nicene habitus, a way of life and mind and spirituality, that are rooted in three deep and embracing strategies.

The three strategies below are the essence of Nicene theology. These are not checklists but the core of belief, the kind of belief that shapes everything in every way. To be Nicene then is to indwell these three strategies. I believe most Christian theologians today are not so much Nicene as they are Reformed, Lutheran, Baptist, Anglican, Presbyterian, or Methodist. They may be “Nicene” as part of that but other elements tend to overshadow the Nicene habitus. To say you are “Nicene” then is to affirm the following three strategies as central to one’s habitus. They are most characteristically central in Eastern Orthodoxy.

Remember, Ayres is not speaking here of Nicene theology as a creed to be confessed or propositions to affirm but as a way of life, as a habitus of mind and body.

Strategy 1: The Unity and Diversity of the Trinity.

“The first and the most fundamental shared strategy is a style of reflecting on the paradox of the irreducible unity of the three irreducible divine persons. Pro-Nicenes reflect on this mystery, I shall argue, always bearing in mind the absolute distinction between God as the only truly simple reality and creation. Bearing this is principle in mind pro-Nicene discussion of the divine persons remains highly austere, and discussion of the individual persons is strongly shaped by the consequences of the divine distinction and simplicity” (278). “It is fundamental to all pro-Nicene theologies that God is one power, glory, majesty, rule, Godhead essence, and nature. In summaries of pro-Nicene Trinitarian theology found across the Mediterranean, and in countless asides in the course of exposition and polemical argument, the assertion that God is a unity in these respects is universal” (279).

They are not interested, then, in “developing a detailed account of what it means to be a divine hypostasis in any generic sense” (280).

Unity, then, is central and this means as well an affirmation of the “inseparable operations” of Father, Son, and Spirit. What “one” does each does. Only in this way can one sustain Nicene theology’s “simplicity” of God. Thus, “Because God is indivisible the persons cannot be understood to work as three divided human persons work” (281). There is also a profound admission of unknowing in the great gulf between God and creation.

Hence, Ayres contends no analogy from creation to God works toward knowledge of God’s essence. “… we can say that we never find descriptions of the divine unity that takes as their point of departure the psychological inter-communion of the three distinct people” (292). I think then it would be consistent to say to understand how Father and Son relate we are not to infer from how human fathers and sons relate. The divine persons are “irreducible within the irreducible essence” (295).

Ayres: “the deepest concern in pro-Nicene Trinitarian theology is shaping our attention to the union of the irreducible persons in the simple and unitary Godhead” (301).

Strategy 2: Christology and Cosmology

Here we find how Strategy 1 works out in redemption, and redemption is understood through incarnation and in particular through union with or participation in Christ. The Word present in Christ is the “ultimate agent in the process of redemption” (305). The emphasis in Calvin on union with Christ, as well as in other Christian traditions, relies upon and develops this Nicene christological center of redemption.

Strategy 3: Anthropology, Epistemology, and the Reading of Scripture

Ayres now draws us into the purification process: there is what he calls a “dual-focus.” That is, “where problems with unsanctified human thinking and action — and the cure for those problems — are described by exploring how human beings should possess a trained soul that animates the body and attends to their joint telos in the divine presence through contemplation of God” (326).

The soul, which is connected to “image of God” in pro-Nicene theologians and theology, is to be purified so the body can be purified so the person can contemplate and lead to further purification in the process of theosis.

Scripture is read, which seems to be obvious now, through the lens of this regula fidei of pro-Nicene Trinitarian thinking and habitus. One might call this, then, the Nicene “theological interpretation of Scripture.” Scripture’s aim is usher the human reader into the creation and saving work of the Triune God.

Yes, of course, this post reflects recent blog discussions about eternal subordination, Nicene orthodoxy, one-three wills, and inseparable operations. Bruce Ware has just recently responded on these matters, which you can read here. His essay frustrates because, while he wants to acknowledge and affirm pro-Nicene theology, his way of affirmation seems reluctant. Thus,

Where I have always hesitated is with biblical support put forth by others for the twin doctrines of eternal generation (Son) and eternal procession (Spirit), sometimes called the doctrine of the eternal modes of subsistence. Because of this, though I have never denied this doctrine, I have been reluctant to embrace it. I have craved biblical support and yet have not been convinced by what has been offered.

I’m all for biblical support, and one should not equate Nicene theology with what is explicitly taught in the Bible, but how does “reluctant to embrace it” square with

The answer emphatically, and for all proponents of our view whom I know, is no. We have never denied this doctrine, and indeed we affirm it as declaring very important truths about the eternal relation between the Father and the Son, the eternal deity and unity of both the Father and the Son, and the eternal Fatherhood of the Father and eternal Sonship of the Son?

What if I were to say, I believe in the millennium but am reluctant to embrace it? Who would say I’m a millennialist?