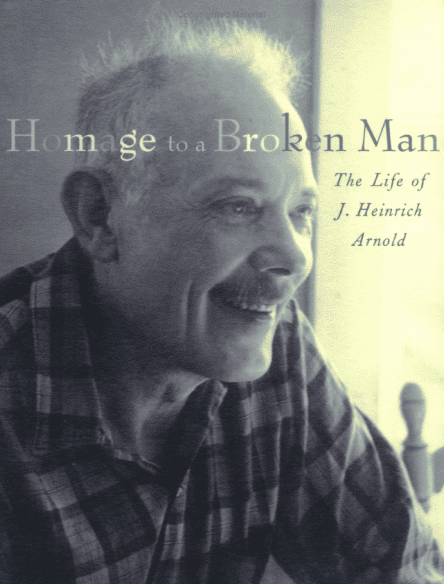

The best way to sort out “what” an Anabaptist is is by finding the stories of Anabaptists. Peter Mommsen’s exceptional study, Homage to a Broken Man, the story of J. Heinrich Arnold, is one of the finest ways to learn what Anabaptism (really) is.

The best way to sort out “what” an Anabaptist is is by finding the stories of Anabaptists. Peter Mommsen’s exceptional study, Homage to a Broken Man, the story of J. Heinrich Arnold, is one of the finest ways to learn what Anabaptism (really) is.

In fact, the best an Anabaptism is found here and so too is the worst of Anabaptism.

Before we get there, I repeat what has been said here a number of times, namely, the sketch of Anabaptism by Harold S. Bender‘ as found in his classic essay called The Anabaptist Vision. No, it is not true that all Anabaptists agree with Bender, and No, some today (like Thomas Finger, in his big study A Contemporary Anabaptist Theology, or J. Denny Weaver, Becoming Anabaptist) want to frame things in a different way, but it can be said that Bender’s sketch is the most influential view of Anabaptism of the 20th Century. Anabaptism is largely responsible for the nonconformist impulse of the church — to be sure, it has some connections to those before it, like the Waldensians of Italy, but the Anabaptists were radical in their nonconformity to the State and to State-sponsored churches — that is, the Catholic Church, Lutherans and the Reformed. All non-State churches in the USA, and that’s most, owe some debt to the Anabaptists.

For Bender, the Anabaptists are the full implementation of the Reformation, and he is famous for three features of the Anabaptist Vision:

1. The essence of Christianity, or the Christian life, is discipleship — a committed following of Christ in all areas of life.

2. A new conception of the church as a brotherhood of fellowship. The ruling image of a church among the Catholics and Reformers was more national and institutional and sacramental, while the ruling image for the Anabaptists was fellowship or family.

3. A new ethic of love and peaceful nonresistance. Apart from rare exceptions like Balthasar Hubmaier and the nutcases around Thomas Müntzer, the Anabaptists lived a life shaped by love and nonviolence. They refused to coerce anyone.

Some today think to be an Anabaptist is to follow John Howard Yoder’s Politics of Jesus or Stanley Hauerwas’ various books and essays, and for many it is the non-ecclesial social justice themes that constitutes Anabaptism. I have had conversations with some who say they are Anabaptists who have nothing to do with the church, but this fails at the deepest levels to understand Anabaptism, which from the beginning has been an ecclesial theology rather than a social activist orientation.

But I delay… the point is the story of one man, J. Heinrich Arnold. Born in Germany … and I had my own summary of Arnold’s life when I found Peter’s own interviewed summary of his grandfather’s (Arnold’s) life:

A childhood in the revolutionary Berlin of 1919 and then on a rural commune amid the swirl of Weimar Republic Germany. A controversial father who’s a famous theologian with a Salvation Army background and a commitment to social justice and pacifism. Exile from Nazi Germany at age 21 for refusal to serve in Hitler’s army. True love and a honeymoon that doubles as escape from the Continent. A promise to God to build up a life of radical Christian community according to Jesus’ teachings, which leads to pioneering in the jungles of South America. Banishment to a Paraguayan leper colony. The heartbreaking loss of two baby daughters. Marching in Selma for civil rights. Rebirth, forgiveness, and reconciliation – but no tidy endings.

One can’t sketch Arnold’s life without telling story after story, so I want to draw your attention to what happened to me as I read this excellent biography.

I saw the exceptional virtues of the Anabaptist vision. Arnold was pious; he was loving; he was passionate; he was a family man, a community man, a justice man, a man who had to do something when he say injustices, a profoundly courageous and trusting man, and he was pacifistic, patient, and flexible. He moved all over the world as he discerned where God might best use him and the community around him. He was a man of the Sermon on the Mount; a man of confession and humility. He trusted others (too much at times). The community around him — the Bruderhof — at times achieved brilliant fellowship, love, and communion.

I saw the problems of the Anabaptist vision. Power mongering, betrayals, sins, economic struggles, vulnerabilities to sicknesses and diseases, stresses beyond measure for families and marriages … at times the community becomes cult like, coercive, untrusting, fracturing and fractured, and unwilling to grant freedom where it needs to be granted. The community around him — the Bruderhof — sometimes betrayed its idealistic visions. Discipline in the community sometimes runs seriously off course.

You can believe in all the Anabaptist ideals you want; you can colonize them to your own theories; but in the end the Anabaptist vision is best understood when you know the stories of people like Menno himself or in stories like that of J. Heinrich Arnold. No one knows his story better than Peter Mommsen, no one has told that story better than Mommsen, and hence no one can grasp the essence of the Anabaptist vision better than one who knows these kinds of stories.

Anabaptist stories like this one reveal that if one wants to try the deep tradition of Anabaptism one should know it is a challenge still not yet achieved in full but often found in glimpses of brilliant sunlight.

Anabaptism is not a theory; it is a way of communal life. Mommsen’s story gives us a genuine slice of the reality of that communal life.