I am preparing to lead a short Bible study on the book of Job using the recent book How to Read Job by John Walton and Tremper Longman III as a guide. The book of Job provides an excellent forum for discussing the nature of Scripture as the word of God, God as creator, and God’s rule of creation. All of these are issues we must deal with in an consideration of science and Christian faith or the relevance of Christian faith in the 21st century. The questions we ask today are not enormously different than those asked by the original audience of Job, but the baggage we bring to the text of Scripture seems to have grown. We need to learn to read the Bible on its own terms, not according to our human (western, modern, …) rules.

I am preparing to lead a short Bible study on the book of Job using the recent book How to Read Job by John Walton and Tremper Longman III as a guide. The book of Job provides an excellent forum for discussing the nature of Scripture as the word of God, God as creator, and God’s rule of creation. All of these are issues we must deal with in an consideration of science and Christian faith or the relevance of Christian faith in the 21st century. The questions we ask today are not enormously different than those asked by the original audience of Job, but the baggage we bring to the text of Scripture seems to have grown. We need to learn to read the Bible on its own terms, not according to our human (western, modern, …) rules.

Part One of How to Read Job addresses the question of reading Job as literature. The book of Job is not history and it is not, actually, about Job. Both Walton and Longman agree that the book of Job is about God and the way God runs the world. Two major questions drive the book. First: Is it good policy for God to bless the righteous? Blessing the righteous just buys pseudo-loyalty doesn’t it? And second, Is it it just when God allows righteous people to suffer?

These two challenges set up the focus of the book as it pertains to God’s policies in the world: it is not good policy for righteous people to prosper (for that undermines the development of true righteousness by providing an ulterior motive). In tension with that, it is not good policy for righteous people to suffer (they are good people, the ones who are on God’s side). So what is God to do? (p. 15)

I think we can take these questions and pose some additional questions that encompass all of Scripture. Why did God create humans capable of sin? Why was the snake in the garden? Why do the wicked prosper? Why does God show mercy? Why are there tsunamis, earthquakes, hurricanes and tornadoes? Why did God apparently (assuming evolution is correct) use years of death to shape the world, from the origin of an oxygen environment down to the present day? Why is the death of Jesus important? Why are hell and judgment important biblical concepts? Why are Christians sometimes horribly persecuted? All of these bear on the larger question of how God runs the world. It isn’t always clear from a human perspective.

What big questions do you see in Scripture?

What is on trial in the book of Job?

I have heard a number of Christians claim that evolutionary creation runs counter to the nature of God. And, apparently ignoring the serpent in the garden, that the introduction of sin and evil must be laid at the feet of humans to preserve God’s integrity and justice. But is this what the Bible teaches? Perhaps Job will help us as we look for answers.

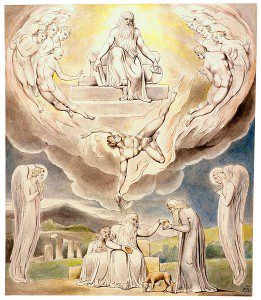

The book of Job is a work of theological literature. Both Longman and Walton see it as a sophisticated and carefully constructed work. The book consists of a prologue and opening lament (ch. 1-3), a cycle of dialogue between Job and his three friends (ch. 4-27), a wisdom hymn (28), a discourse by Job (ch. 29-31), a discourse by Elihu (ch. 32-37), a discourse by God (ch. 38-41) and an closing and epilogue (ch. 42). (The drawings are by William Blake – available on Wikipedia.)

The book of Job is a work of theological literature. Both Longman and Walton see it as a sophisticated and carefully constructed work. The book consists of a prologue and opening lament (ch. 1-3), a cycle of dialogue between Job and his three friends (ch. 4-27), a wisdom hymn (28), a discourse by Job (ch. 29-31), a discourse by Elihu (ch. 32-37), a discourse by God (ch. 38-41) and an closing and epilogue (ch. 42). (The drawings are by William Blake – available on Wikipedia.)

Though many modern interpreters have found the book lacking in cohesiveness, we would contend that each of these components of the book plays a significant role in the development of the book’s purpose. The various styles of literature used by the book include dialogue, discourse, narrative, hymn, and lament. All of these are woven together into a poignant piece of wisdom literature. None of these parts can be easily written off as later additions or as redundant once we understand the role that each plays in the book. (p. 20)

While the book of Job fits into the larger world of ancient Near Eastern literature, it is distinctly different in the way it portrays Job and God. Job thinks like an Israelite. God alone is wise. The book doesn’t mirror the surrounding views – in a sense it responds to them. “It is remarkable that some could still suggest that the book of Job borrows from the ancient Near Eastern exemplars. … A more defensible model sees the mentality of ancient Near Eastern literature as a foil for the book of Job. Job’s friends are the representatives of the ancient Near Eastern perspective, and their views are soundly rejected.” (p. 32) Walton and Longman point out out several ways the text responds to the culture, including the following: (1) There is no “great symbiosis” because God does not have needs for humans to satisfy. (2) The text is interested in the justice of God, while just gods are not a concern in the ancient Near East. (3) The text is concerned with righteousness as an abstract concept, and one that goes beyond the ancient world. (4) No ritual offenses are considered (contrary to the literary parallels). (5) Divine wisdom is a major theme.

The book of Job is not history. The character of Job may or may not be based on a real person known to the original author and audience – by reputation at least. It doesn’t matter. Longman and Walton don’t mince words here: “this book is manifestly and unarguably in the genre category of wisdom literature rather than historical literature.” (p. 35) And a little later on the same page, “We would be mistaken to think that the author seeks to unfold a series of historical events.” (p. 35) They run through some of the reasons for this conclusion (for example, no stenographer recording heavenly prologue or the dialogues). The excessive extremes that frame the story. Job is exceedingly wealthy, he is undeniably righteous, no space is left for easy outs. The reader must grapple with the central question.

We therefore adopt the position that, though Job himself may have been a real person who actually lived, the rest of the book is a literary work of art providing a wisdom discussion that is framed by extremes. … This allows us to consider the extreme and artificial scenario the author has constructed so that we can engage in a deep investigation of an important philosophical issue without having to continually cope with the muddied waters of the normal ambiguities of people and their circumstances. Whether we label it a thought experiment or simply a hypothetical scenario built around extremes, we can encounter the God-given message of the text undistracted from incidental curiosities and without the angst that comes with wondering why God killed Job’s children. (p. 39)

I suppose that we could argue that God should not have allowed (or inspired) the original author to include such troubling elements as the wager with the challenger and the killing of Job’s children. However, this may well be imposing modern sensibilities on an ancient text. We find these to be distractors, but they need to be taken for their literary intent as extremes not as moral statements.

How would you describe the genre of Job?

How does this influence the way you interpret the book?

If you wish to contact me directly you may do so at rjs4mail[at]att.net

If interested you can subscribe to a full text feed of my posts at Musings on Science and Theology.