Many of us were introduced to the Christ and Culture issue by reading H. Richard Niebuhr’s Christ and Culture and it has stood the test of time as it is now still routinely purchased and read in its sixth decade. In his influentialism approach to Christ and Culture I saw the essential typology for American Christians — both liberal and conservative, evangelical and otherwise. So I read more of H. Richard Niebuhr’s books (though I confess I don’t think I’ve read an entire book of his more famous brother, Reinhold).

This led me to read Kuyper. My colleague, David Fitch, often says something about “Kuyperianism” and in reading Yoder and Hauerwas over the years I’ve encountered Kuyper so I wanted a firmer handle. I had dabbled in James Bratt’s Abraham Kuyper: A Centennial Reader but then James Bratt’s full biography of Kuyper appeared, and I read it. It is called Abraham Kuyper: Modern Calvinist, Christian Democrat. Bratt gave me categories and perspective to read the former volume that collected his essays. I also dipped into a devotional study by Kuyper, and read into some of the newer collections of Kuyper’s works.

This was all done to sketch a Kuyperian theory of Christian involvement in culture and the state, and for me it had to do with how Kuyper and his sort understood the kingdom of God. I had an outline with way too many quotations and it got a bit unwieldy for the project I was working on when I discovered my favorite Kuyperian: Rich Mouw.

Rich Mouw wrote Abraham Kuyper: A Short and Personal Introduction. What Mouw did for me was to give bigger handles to comprehend Kuyper and he had a hermeneutic of Kuyperianism that gave me firmer footing for reading Kuyper. So I let Mouw be my guide in Kingdom Conspiracy and I’m glad I did, though quoting Kuyper himself would have made the section thicker and longer (and the book got long enough as it was).

One should not, I suspect, equate “influentialism” with Kuyperianism for Niebuhrianism would also be influentialism. But one of the big themes for Kuyper was how best does the Christian engage culture and society and state. Kingdom is not infrequently connected to the vision and the influences. That’s another topic for the Kuyperians.

Rich Mouw is my favorite Kuyperian. Tim Keller would be my second. (I like Keller’s focus on the church, but more of that below.) I don’t know Kuyperianism intimately enough to say who is the best Kuyperian, but I suspect not many (if any) outrank Mouw.

Rich Mouw is my favorite Kuyperian. Tim Keller would be my second. (I like Keller’s focus on the church, but more of that below.) I don’t know Kuyperianism intimately enough to say who is the best Kuyperian, but I suspect not many (if any) outrank Mouw.

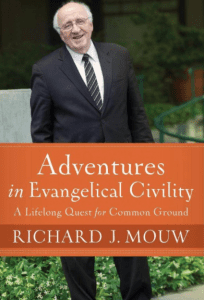

I want in this post to discuss Rich Mouw’s splendid new Kuyperian book called Adventures in Evangelical Civility: A Lifelong Quest for Common Ground. Not all Calvinists or all Kuyperian are on the quest for common ground and not all of them are close to Mouw’s admirable ability to conduct conversations with civility. In this book, which is a memoir like narrative through his intellectual life — a meandering through scholars who have made an impact on him (and the names and breadth of his reading illustrate why he has become so civil), Mouw makes some self claims, and they are these:

I am a Christian

I am a Calvinist

I am a Kuyperian

I am a pietist

I am a professor, philosopher and theologian

I am a seminary provost and president

I am retired

Of the 2d, 3d, and 4th, with ten total points, I’d say he is 4 parts Calvinst, 4 parts Kuyperian and 2 parts pietist. But this kind of scoring may create mis-impressions. He’s always both Calvinist and Kuyperian and his pietism seems to me have created the man who is both civil and always seeking common ground, not least in his deeper-than-most appreciation for variants like Mormonism or even world religions. Perhaps it is Mouw’s pietism that makes him the kind of civil Kuyperian Calvinist that he is.

An early thinker’s transitional moment:

As I reported earlier, I started off as a college student endorsing Van Til’s refusal to concede to Edward John Carnell the legitimacy of looking for areas of agreement with nonChristians in our apologetic efforts. My attraction to Van Til’s perspective would soon give way to much sympathy for Carnell’s side of the argument. And it wasn’t just because I came to see the attractiveness of Carnell’s approach as a plausible apologetic methodology—although it certainly was that. More importantly, his way of viewing things gripped me experientially. I kept sensing, in various encounters with people beyond the boundaries of evangelical Calvinism, that my theological feet were actually finding real patches of common ground (16-17).

In a quote from Rousseau I couldn’t help but think of the zeal at work in the progressive evangelical crowd who have at times fallen for the idea that the gospel is social justice activism:

“The transition from the state of nature to the civil state,” he remarks, “produces a quite remarkable transformation within—i.e., it substitutes justice for instinct as the controlling factor in [one’s] behavior, and confers upon [one’s] actions a moral significance that they have hitherto lacked” (56).

Mouw’s core in this book is the search for and discovery of common patches where people of difference may stand together for a common cause or belief. When Evangelicals for Social Action began to fragment, Mouw’s Kuyperianism kept him grounded but still capable of finding common places for civil discussion and action, even when he did disagree with Yoder — here’s how he expresses Yoder’s theory of atonement:

It is important to pay attention to various theories of the atonement, including the moral example theory, of which Yoder’s is a very sophisticated version. But none of this should ever detract from a central emphasis on the once-for-all transaction that has traditionally been associated with the motifs of substitution, payment, and sacrifice (68).

Furthermore, the present-day Anabaptists and their fellow pilgrims are right to call us to account for the ways we often identify Christian discipleship with specific political programs and ideologies. The church’s record in aligning itself with political power, and in freely giving its blessing to various military campaigns, is not a noble one. For all of that, though, I am not ready to concede that the solution for Christian disciples is to abandon all efforts to employ the political means available to us as citizens to pursue Christian goals. Nor am I convinced that a thoroughgoing pacifism is mandated for Christian disciples (74).

When it comes to finding common ground and compromise for the sake of justice, Mouw:

I would be happy to accept this statement of public policy as an accomplishment made possible by a careful exploration by persons who, in spite of serious worldview differences, possess a shared sense of justice grounded in a common createdness (79).

This brings into play an earlier discussion in the book on the image of God and createdness. Our common createdness provides the platform for common ground, civility, conversation, and compromise for the common good. Including language that jumps from the Christian box into common discourse:

[Jimmy] Carter related “thick” to “thin” by showing how a public address on policy matters can employ the language of a broad-ranging public discourse while being able to link each key point to concrete biblical teaching. It illustrates for me a workable principle: think “thick” within the Christian community and then speak “thin” in the public arena (80).

For Mouw activism isn’t simply the aim and, in fact, there’s very little indication of the kind of social activism Mouw engages in his life. Rather, the mode, namely, civility, is emphatic.

I have experienced a shift in my own focus, as an evangelical who cares about public involvement, from urging evangelicals simply to get involved in public life to encouraging them to work at exercising that involvement in the right spirit. This led, for me, to a sustained emphasis on the concept of civility in public life (82).

… the importance of drawing on Calvin’s overall perspective for seeing the church as a place in which we learn how to cultivate the kind of virtue that is appropriate and necessary for public life (85).

He found the Barth vs. Brunner to be dichotomies that were resolved by Kuyper in the idea of “common grace”:

Common grace, in contrast, is typically set forth by the neo-Calvinists as a divine strategy for bringing the cultural designs of God to completion (104).

There is a lot about law in common grace and natural law, all mentioned at some level in Mouw’s book. Instead of moving toward grace and love, Mouw moves more readily toward the I-Thou in the covenant concept.

He turns at one point to a younger Nicholas Wolterstorff who typologized three kinds of Calvinsts: doctrinalists, pietists, and Kuyperian. How is the Kuyperian depicted by Wolterstorff? “the Bible is meant to give us our cultural marching o; orders, , instructing us in the ways of discipleship in the collective patterns of life in the larger human community (120) … it is about being aligned with God’s culture-transforming purposes in the world” (120). Ah, that’s a very common way of understanding Kuyperianism but Mouw surprises: he sees himself as a pietist. Well, OK, I say to myself, and I see that pietism especially pervading his work in common ground and in civility. But his focus in this book over and over has to do with culture and culture-influencing and the public square.

Our intellectual lives, our cultural engagements, our relationships with others in the body of Christ—all of these must be guided by a personal and communal godliness, by hearts that desire the kind of holiness without which none shall see the Lord (124).

Mouw makes some strong critiques of identity politics today and the fragmentation of people into identities that end up in clusters rather that common ground arising from our common image of God. Hence, “If we take the Pentecostal alternative to Babel seriously, we cannot allow multiculturalism simply to be defined in terms of the Babel experience” (137).

Like Michael Horton, he believes in the village green (common ground) but knows it is insufficient for ecclesiology. Hence, evangelicalism is the common ground but the narrower expression for him is Calvinism and Reformed churches.

A great quote from Bavinck:

‘We must remind ourselves that the Catholic righteousness by good works is vastly preferable to a protestant righteousness by good doctrine. At least righteousness by good works benefits one’s neighbor, whereas righteousness by good doctrine only produces lovelessness and pride. Furthermore, we must not blind ourselves to the tremendous faith, genuine repentance, complete surrender and the fervent love for God and neighbor evident in the lives and work of many Catholic Christians.” (199)

Here is my favorite set of lines from this entire book, one that I resonate deeply with:

Many of us have had to move beyond a harsh acceptance of strong convictions to a gentler spirit of civility. But many of the younger evangelicals today need to move in the opposite direction. They don’t have to work as hard at being civil people, but they do need to be guided in the direction of strong convictions. They aren’t very literate biblically. Nor do they have the theological memories of those past struggles that gave birth to the strong convictions in the evangelical community (220).

It is hard to know how to critique a memoir like this but I do want to register a pervasive concern I had with the book. Rich Mouw is a statesman, a theologian, and a church man, but this book is about his public life. I would like to have seen more about the church: his church, the role of the church as church in society, and how the church can embody ways of life that the culture and the state will not because their “worldview” is otherwise. The absence of the church, I’m confident, is not because Mouw is not in the church; it is because this book is about seeking common ground with outsiders and insiders who differ.

Another way of engaging culture and the state is for the church to be the church and as a church witness to an alternative kingdom at work in this world. The distinctive difference I see between the Kuyperian framing of topics and the Anabaptist has to do with the aim, the end, the primary focus of one’s energies: is it the church or culture? is it the church as a means of influencing and transforming culture? is it the church as comprised of citizens for the sake of culture?

Too many today think the primary aim of the Christian is to make the world a better place. Whether a person gets juiced from liberation theology, social gospel, conservative evangelical social activism, or Kuyperianism, the issue is real-er than real today. Many today are convinced of these forms of activism and are completely unsure how important the church is.