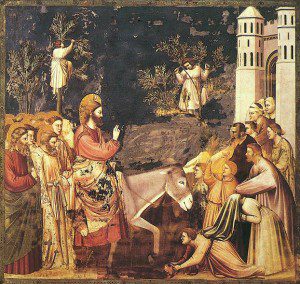

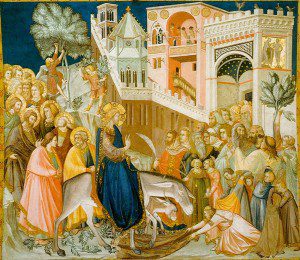

This last Sunday we celebrated the triumphal entry of Jesus into Jerusalem, setting off the Holy Week events. The echoes of Scripture in this event are often recognized and preached, but still worth another look. Richard Hays in Echoes of Scripture in the Gospels looks at these passages in the context of their message concerning the identity and mission of Jesus. This is an incident recorded in all four gospels, although with slightly different emphasis in each.

This last Sunday we celebrated the triumphal entry of Jesus into Jerusalem, setting off the Holy Week events. The echoes of Scripture in this event are often recognized and preached, but still worth another look. Richard Hays in Echoes of Scripture in the Gospels looks at these passages in the context of their message concerning the identity and mission of Jesus. This is an incident recorded in all four gospels, although with slightly different emphasis in each.

There are several take-home messages from the triumphal entry.

The accounts are not identical. First – and this probably escapes most – these accounts help us learn how to read scripture and understand inspiration. When the passages are preached, read, taught individually they are clearly the same, that is they record one historical and significant event. Placed side by side there are several striking discrepancies.

In Mark 11:1-11 Jesus sends two disciples to get a colt and bring it; Jesus rides the colt down to Jerusalem; People spread cloaks and branches; Shout Hosanna; Jesus enters the temple, looks around and leaves. The next day he returns and cleanses the temple.

In Matthew 21:1-11 Jesus sends two disciples to get a donkey and her colt and bring them; Jesus rides one, the other or both? down to Jerusalem; People spread cloaks and branches; Shout Hosanna; Jesus enters the temple, cleanses it, and then leaves the city.

In Luke 19:28-45 Jesus sends two disciples to get a colt and bring it; Jesus rides the colt down to Jerusalem; People spread cloaks and praise God; Jesus enters the temple and cleanses it.

In John 12:12-19 The people take branches and meet Jesus; Jesus finds a donkey and sits on it; the cleansing of the temple occurred at a Passover probably two years earlier.

Multiple schemes, generally often involving four Passover trips to Jerusalem and two cleansings, have been invoked to harmonize these accounts. I don’t particularly want to get into arguments about the details – the discrepancies are not significant to the story. However, I do think that these differences should teach us something important about how we are to read and interpret Scripture. The Gospels are not records of itineraries, they are theological interpretations of the events in the life and death of Jesus. The authors, while inspired by the Holy Spirit to convey the message, were free to rearrange and structure to best get the point across. They each cast a slightly different light on the events and we are the richer in understanding for it.

Gentle and Riding a Colt. Second (and more important were it not for the proof-text faith of so much of conservative Christianity), the authors draw heavily on the Old Testament Scriptures to convey the theological importance of the triumphal entry. It was not until later after all had been accomplished that the disciples realized the significance of these events as John makes explicit: At first his disciples did not understand all this. Only after Jesus was glorified did they realize that these things had been written about him and that these things had been done to him. John 12:16. (The picture was taken almost 16 years ago, looking from the Tower of David (approximate location of Herod’s palace) toward Temple Mount and the Mount of Olives.)

Gentle and Riding a Colt. Second (and more important were it not for the proof-text faith of so much of conservative Christianity), the authors draw heavily on the Old Testament Scriptures to convey the theological importance of the triumphal entry. It was not until later after all had been accomplished that the disciples realized the significance of these events as John makes explicit: At first his disciples did not understand all this. Only after Jesus was glorified did they realize that these things had been written about him and that these things had been done to him. John 12:16. (The picture was taken almost 16 years ago, looking from the Tower of David (approximate location of Herod’s palace) toward Temple Mount and the Mount of Olives.)

The key passages are Isaiah 62:10-12 and Zechariah 9:9-13. Matthew and John connect the colt to Zechariah 9, while Mark and Luke merely report the event.

Matt. 21:5: “Say to Daughter Zion, ‘See, your king comes to you, gentle and riding on a donkey, and on a colt, the foal of a donkey.”

John 12:15: “Do not be afraid, Daughter Zion; see, your king is coming, seated on a donkey’s colt.”

Zechariah 9:9 Rejoice greatly, Daughter Zion! Shout, Daughter Jerusalem! See, your king comes to you, righteous and victorious, lowly and riding on a donkey, on a colt, the foal of a donkey.

Isaiah 62:11 The Lord has made proclamation to the ends of the earth: “Say to Daughter Zion, ‘See, your Savior comes! See, his reward is with him, and his recompense accompanies him.'”

Matthew blends Isaiah 62 and Zechariah 9 and thus sends us back to both of the original passages.

[T]he opening words of Matthew’s quotation differ slightly, but significantly from Zechariah 9:9 in either the Hebrew text or the LXX. They agree instead verbatim with a phrase taken from Isaiah 62:11 LXX … The difference from Zechariah is subtle, but Matthew’s choice of word can hardly be an accident. The passage in Isaiah is a dramatic oracle of salvation for the city of Jerusalem. Matthew would have found the surrounding context, particularly in its LXX form, laden with christological significance. (p. 252)

When we read the story of the triumphal entry we should have both Zechariah 9 and Isaiah 62 ringing in the back of our head. This is the king and savior of Jerusalem and all the world coming humble and gentle riding on a colt.

This brings us to the second point Hays emphasizes.

Matthew deletes from his quotation of Zechariah 9:9 the phrase “triumphant and victorious is he.” … Since Matthew has cited the surrounding material in full, this can hardly be a case in which the reader is meant to recall the continuation or wider context of the quoted material; this looks more like a case of deliberately editing-out of a phrase. … The most striking effect of the omission is to focus attention on the description of Jesus as πραΰς (“humble” or “gentle”), a significant Matthean motif (cf. 5:5, 11:29). “The Son of David” who enters Jerusalem riding on “on a donkey and on a colt, the foal of a donkey” is not a conquering military hero but a lowly gentle figure who is reshaping Israel’s messianic hope in a way that could hardly have been anticipated – a way, indeed, that will lead to the cross. (p. 153)

John’s citation doesn’t go directly to Isaiah 62, but also omits the reference to “triumphant and victorious is he.” Perhaps for both Matthew and John victory comes after the cross and resurrection. Thus, it would be out of place (too early) in the description of these events.

The Coming One. The other major echoes of Scripture come in the praise of the people.

The Coming One. The other major echoes of Scripture come in the praise of the people.

Mark 11:9-10 “Hosanna! Blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord! Blessed is the coming kingdom of our father David! Hosanna in the highest heaven!”

Matthew 21:9 “Hosanna to the Son of David! Blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord! Hosanna in the highest heaven!”

Luke 19:38 “Blessed is the king who comes in the name of the Lord! Peace in heaven and glory in the highest!”

John 12:13 “Hosanna! Blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord! Blessed is the king of Israel!”

Mark and Matthew identify Jesus with David and thus the coming Davidic king. Luke and John clearly identify Jesus as king. The phrase “blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord” is an echo of Psalm 118, “the climactic passage of the Hallel psalms, whose association with Passover and the Feast of Tabernacles render them fraught with eschatological hope.” (p. 151)

The stone the builders rejected

has become the cornerstone;

the Lord has done this,

and it is marvelous in our eyes.

The Lord has done it this very day;

let us rejoice today and be glad.

Lord, save us!

Lord, grant us success!

Blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord.

From the house of the Lord we bless you.

The Lord is God,

and he has made his light shine on us.

With boughs in hand, join in the festal procession

up to the horns of the altar.

You are my God, and I will praise you;

you are my God, and I will exalt you.

Give thanks to the Lord, for he is good;

his love endures forever.

Psalm 118:22-29

Hays notes:

In Mark, the crowd celebrates Jesus’ entry with words that anticipate the coming kingdom of David, and the inference is that Jesus – the figure acclaimed by their chants – is the Coming One, the one who comes in the name of the Lord. … Matthew resolves any possible uncertainty by having the crowd explicitly identify Jesus as “the Son of David,” precisely the appellation already conferred by the narrator upon Jesus from the very beginning of the story (Matt. 1:1) (p. 151-152)

Luke also identifies Jesus as the Coming One but omits any direct reference to David. Hays suggests that perhaps Luke omits direct reference to David here and in other passages identifying Jesus as the Coming One in order to emphasize that this is not the expected conquering royal victor. Here and in the response to John’s disciples in Luke 7:18-23, the emphasis is on “Jesus’ unexpected peaceful way of bringing in God’s promised reign.” (p. 252)

John has likewise interpreted the Coming One of Psalm 118 as the king, specifically the King of Israel.

Strikingly, John 12:12-16 is the only passage in John’s Gospel that explicitly links Jesus’ titles as “King” and “Messiah” to specific scriptural subtexts. In this key text John assures the reader that the ascription of kingship to Jesus is correct, but he also signals that the character of this kingship can be understood only by reading backwards to redefining the meaning of “king” in the light of the Gospel’s revelatory narrative about Jesus. (p. 325)

A suitable reflection for the start of Holy Week.

————————————————————————————–

If you wish to contact me directly, you may do so at rjs4mail[at]att.net

If interested you can subscribe to a full text feed of my posts at Musings on Science and Theology.