The author of this blog is a missionary in North Africa with Pioneer Bible Translators. She, along with her husband and three little girls, lives on the outskirts of a refugee camp in a very politically unstable part of the world. There they are working to facilitate disciple-making, Bible translation and mother tongue literacy among two least-reached Muslim groups. Despite the occasional craziness, they really love what God has called them to do.

The author of this blog is a missionary in North Africa with Pioneer Bible Translators. She, along with her husband and three little girls, lives on the outskirts of a refugee camp in a very politically unstable part of the world. There they are working to facilitate disciple-making, Bible translation and mother tongue literacy among two least-reached Muslim groups. Despite the occasional craziness, they really love what God has called them to do.

For reasons that remain a mystery to this day, our teammates’ daughter Rebekah was born without a heartbeat. She was dead for over eleven minutes, and by the time she was revived the damage was permanent. She is now a precious three year old with a head full or curls who breaks into a lopsided grin every time her big brother explodes into the room. But she cannot stand on her own and she cannot talk. She is fed through a tube that goes straight into her stomach. She has a machine that shakes loose mucus in her lungs, another that helps her cough, another that helps her breath, another which monitors her oxygen levels. She has been hospitalized more times that I can remember for seizures that break through her battery of medications.

I love Rebekah’s parents dearly and I have grieved the health complications that have meant they are no longer my neighbors in North Africa more than just about any other loss in my life so far. I love Rebekah with all my heart.

But I have always been super weird around her.

I have held her only a few times, usually only when asked, and I am always terrified of hurting her fragile body. I am extraordinarily careful to try and not say anything offensive, to not refer to Rebekah as “sick” or “broken” or anything that might come across pejorative. I probably deflect too much, complementing her beautiful eyes or giving voice to the jokes we can pretend she is making at our expense. As much as I love her, I don’t always know how to act or what to say. I’m awkward around her, and as much as I hate it, I know it’s true.

Last summer Rebekah’s family made a trip back to North Africa for a visit. We all audibly hoped it would be the miracle trip ushering their family back to life and ministry in the camps despite Rebekah’s health challenges. But in the back of our minds I think we all knew better. This trip was goodbye.

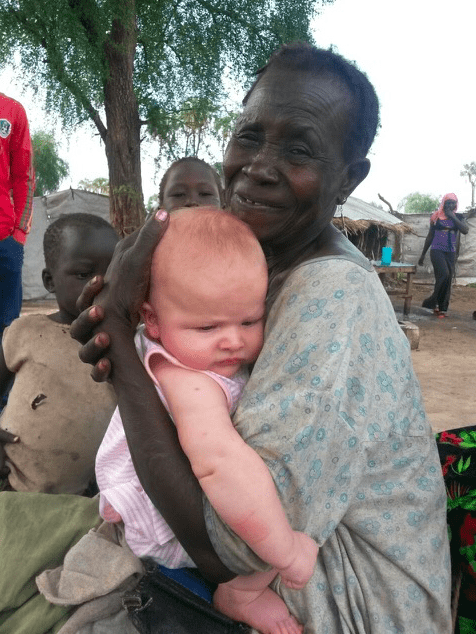

From practically the moment Rebekah’s family stepped off that bush plane, grappling with bags of contingency medications and an inconveniently sized wheelchair, our local friends were all there, swarming around her and doing everything wrong. Almost every single day, a woman would pluck Rebekah up out of the rope bed where she was resting in the shade, and walk around with her in casual tenderness while shooing chickens off the porch or chatting loudly with a neighbor. There were lots of questions – what kind of food are you putting in that bag? Does the tube in her stomach hurt? Can she cry? How does her chair work? They touched her and talked to her unabashedly in languages she will never understand. And often someone would fearlessly and curiously run their hands over that head of curls and say with such love “Mashallah, she’s still so sick isn’t she? Her mind is broken.”

They showed up unannounced, asked uncomfortable questions, touched without extreme sensitivity.

And it was absolutely beautiful to witness.

While I had spent my time tiptoeing anxiously around this terrible thing we call suffering, like I was afraid of waking something up or drawing attention to something we’d all rather not notice, our North African friends rushed at the pain with open arms and bravely loved it in the wide open. Because in their world, pain and loss and grief are so prevalent one could ever pretend like it isn’t sitting right here next to us. And for those two weeks, I witnessed near-strangers love the daughter of my dear friends better than I had, joyfully picking up something beautiful and broken and singing it songs, even if they did so with tears streaming down their faces.

We’re awkward around suffering. We’d much rather ignore it and pretend it isn’t real. And many of us live the kind of lives that allow us to actually play make-believe for a while. But in the end, all that really does is create distance between us and those who are hurting and ultimately, delay our own introduction to the reality of heartache in this life. Because our turn is coming too. No one gets a pass.

Jesus strikes me as very North African sometimes. He does a lot of touching and holding and talking to hurting things. He doesn’t tend to hold back with his questions or skin contact. I can totally see him walking down a dirt path through the refugee camp with Rebekah in his arms, pointing out so-and-so’s house to her and joking with the scrawny kids loping along beside them. Not because he’s denying the stark disappointments etched into the surfaces of every reality around him. But because he’s not afraid of them.

It takes courage to love – and to keep loving over and over again every day – all the beautiful things in this life that will hurt you. But we are called to. I live among brave people. Perhaps you do also. May we all take courage from their examples.