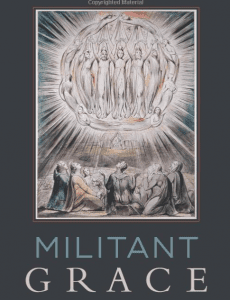

The word sovereignty, a favorite of some theologians, tends to move in the direction of control, of providence, of judgment, of making the world right and it is also closely aligned with holiness. But Philip Ziegler, in Militant Grace: The Apocalyptic Turn and the Future of Christian Theology, aligns sovereignty with love and grace and this leads to a different framing of what providence and even judgment might mean.

Ziegler opens his chapter on sovereign love examining the three offices of Christ: prophet, priest, king (munus triplex in Latin). NT professors tend to think this approach lacks consistency with how NT authors actually worked; they also know it has become a well-traveled set of categories from systematics, which makes NT professors nervous.

Ziegler opens his chapter on sovereign love examining the three offices of Christ: prophet, priest, king (munus triplex in Latin). NT professors tend to think this approach lacks consistency with how NT authors actually worked; they also know it has become a well-traveled set of categories from systematics, which makes NT professors nervous.

He enters into the spiritual nature of Christ’s rule and turns to Calvin:

As Calvin summarizes, Christ “rules—inwardly and outwardly—more for our own sake, than for his.”11 Here, in other words, Christ’s kingship is spiritual because the power by which he reigns is heavenly and not “of this world”; it is spiritual because his dominion is accomplished not by worldly means but rather by virtue of his own priestly and prophetic work;12 and it is spiritual because he is “armed with eternal power” such that “the devil, with all the resources of the world, can never destroy the church.”13 We do well to recognize in all of this the public, gracious, agonistic, and eschatological force of Christ’s spiritual rule as Calvin sets it forth. Calvin’s exposition of the spiritual nature of Christ’s lordship bears the imprint of the witness and language of the concluding verses of Romans 8, and it shares something of their eschatological and apocalyptic tone.

He turns then to Luther, where he finds confirmation of the spiritual reign. Christ’s power gives the Christian freedom in the world. Schleiermacher internalizes this rule to the individual and Harnack even more so. But he finds his cues in Otto Weber whose sees the “spiritual” as eschatological, and this then elides for Ziegler into the apocalyptic.

Thus, the rule of Christ is an eschatological reality that draws those in Christ into that rule in a world where that rule is not known the same way. Which leads Ziegler to Romans 8:31-39.

He makes four summary points of his discussion of Romans 8:

First, the royal office of Christ is exercised not only in and as a consequence of the status exaltationis (state of exaltation; cf. Phil. 2:10, Vulgate) but also and importantly in and as a consequence of the status exinanitionis (state of humiliation; cf. Phil. 2:7, Vulgate). Only when this is so can we grasp the contours of his dominion as a lordship of divine love and recognize that Christ’s royal office consists in “the continuous work of the Crucified One.”

Second, Christ’s kingship is spiritual in and because it is an eschatological reality that even now invades the world pneumatically, repossessing, sustaining, and directing his people in their corporate faith and life amid the yet unruly powers of the old age.

Third, acknowledgment of the cosmic scope of Christ’s lordship requires that theology draw together its understanding of the munus regnum Christi and its account of divine providence generally. … An evangelical doctrine of providence will look to conceive of God’s conservatio (continuing preservation), concursus (cooperation), and gubernatio (governance) by reflecting on the entailments of Christ’s lordship over church and world.

Fourth and finally, faith in Christ’s exercise of his royal office shapes lives ^ of Christian freedom marked by joyful assurance in the midst of adversity and the perplexities of life in the not-yet-redeemed world.